The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (17 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

2.42Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“You must be Billy’s parents. I’d recognize you anywhere!”

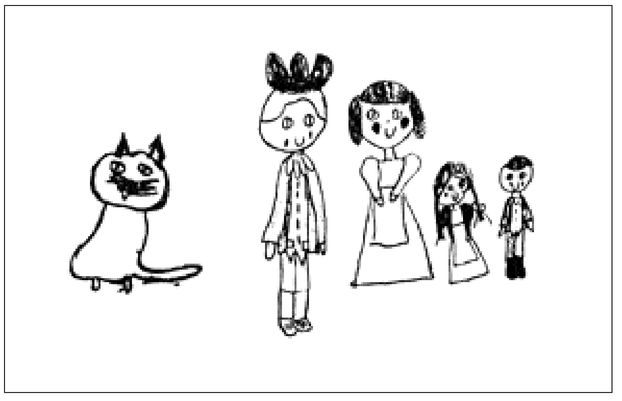

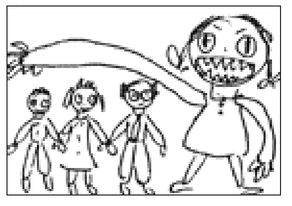

By age four, children are keenly aware of details of clothing—buttons and zippers, for example, appear as details of the drawings. Fingers appear at the ends of arms and hands, and toes at the ends of legs and feet. Numbers of fingers and toes vary imaginatively. I have counted as many as thirty-one fingers on one hand and as few as one toe per foot (Figure 5-4).

Although children’s drawings of figures resemble each other in many ways, each child works out through trial and error a favorite image, which becomes refined through repetition. Children draw their special images over and over, memorizing them and adding details as time goes on. These favorite ways to draw various parts of the image eventually become embedded in the memory and are remarkably stable over time (Figure 5-5).

Fig. 5-5. Notice that the features are the same in each figure—including the cat—and that the little hand symbol is also used for the cat’s paws.

Fig. 5-6.

Pictures that tell storiesAround age four or five, children begin to use drawings to tell stories and to work out problems, using small or gross adjustments of the basic forms to express their intended meaning. For example, in Figure 5-6, the young artist has made the arm that holds the umbrella huge in relation to the other arm, because the arm that holds the umbrella is the important point of the drawing.

Using his basic figure symbol, he first drew himself.

He then added his mother, using the same basic figure configuration with adjustments—long hair, a dress.

He then added his father, who was bald and wore glasses.

Another instance of using drawing to portray feelings is a family portrait, drawn by a shy five-year-old whose every waking moment apparently was dominated by his older sister.

Even Picasso could hardly have expressed a feeling with greater power than that. Once the feeling was drawn, giving form to formless emotions, the child who drew the family portrait may have been better able to cope with his overwhelming sister.

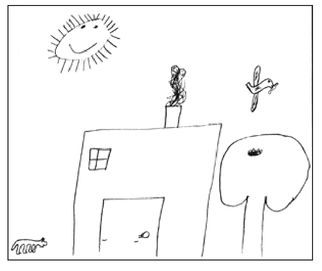

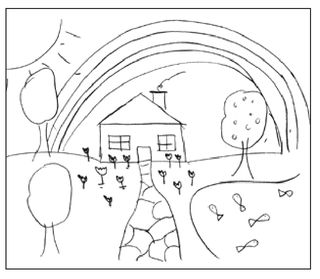

The landscapeBy around age five or six, children have developed a set of symbols to create a landscape. Again, by a process of trial and error, children usually settle on a single version of a symbolic landscape, which is endlessly repeated. Perhaps you can remember the landscape you drew around age five or six.

What were the components of that landscape? First, the ground and sky. Thinking symbolically, a child knows that the ground is at the bottom and the sky is at the top. Therefore, the ground is the bottom edge of the paper, and the sky is the top edge, as in Figure 5-7. Children emphasize this point, if they are working with color, by painting a green stripe across the bottom, blue across the top.

Most children’s landscapes contain some version of a house. Try to call up in your mind’s eye an image of the house you drew. Did it have windows? With curtains? And what else? A door? What was on the door? A doorknob, of course, because that’s how you get in. I have never seen an authentic, child-drawn house with a missing doorknob.

He then added his sister, with teeth.

Fig. 5-7. Landscape drawing by a six-year-old. This house is very close to the viewer. The bottom edge of the paper functions as the ground. To a child it seems that every part of the drawing surface has symbolic meaning, the empty spaces of this surface functioning as air through which smoke rises, the sun’s rays shine, and birds fly.

Fig. 5-8. Landscape drawing by a six-year-old. This house is farther away from the viewer and has a wonderfully self-satisfied expression, enclosed as it is under the arc of a rainbow.

You may begin to remember the rest of your landscape: the sun (did you use a corner sun or a circle with radiating rays?), the clouds, the chimney, the flowers, the trees (did yours have a convenient limb sticking out for a swing?), the mountains (were yours like upside-down ice cream cones?). And what else? A road going back? A fence? Birds?

At this point, before you read any further, please take a sheet of paper and draw the landscape that you drew as a child. Label your drawing “Recalled Childhood Landscape.” You may remember this image with surprising clarity as a whole image, complete in all its parts; or it may come back to you more gradually as you begin to draw.

While you are drawing the landscape, try also to recall the pleasure drawing gave you as a child, the satisfaction with which each symbol was drawn, and the sense of rightness about the placement of each symbol within the drawing. Recall the sense that nothing must be left out and, when all the symbols were in place, your sense that the drawing was complete.

If you can’t recall the drawing at this point, don’t be concerned. You may recall it later. If not, it may simply indicate that you’ve blocked it out for some reason. Usually about ten percent of my adult students are unable to recall their childhood drawings.

Before we go on, let’s take a minute to look at some recalled childhood landscapes drawn by adults. First, you will observe that the landscapes are personalized images, each different from the other. Observe also that in every case the composition—the way the elements of each drawing are composed or distributed within the four edges—seems exactly right, in the sense that not a single element could be added or removed without disturbing the rightness of the whole (Figure 5-9). Let me demonstrate that by showing you what happens in Figure 5-10 when one form (the tree) is removed. Test this concept in your own recalled landscape by covering one form at a time. You will find that removing any single form throws off the balance of the whole picture. Figures 5-9 and 5-10 show examples of some of the other characteristics of childhood landscape drawings.

After you have looked at the examples, observe your own drawing. Observe the composition (the way the forms are arranged and balanced within the four edges). Observe distance as a factor in the composition. Try to characterize the expression of the house, at first wordlessly and then in words. Cover one element and see what effect that has on the composition. Think back on how you did the drawing. Did you do it with a sense of sureness, knowing where each part was to go? For each part, did you find that you had an exact symbol that was perfect in itself and fit perfectly with the other symbols? You may have been aware of feeling the same sense of satisfaction that you felt as a child when the forms were in place and the image completed.

Other books

OBSESSED WITH MY STEP (TABOO NOVELLA) by Zania Summers

High Tide in Tucson by Barbara Kingsolver

Dead Life (Book 3) by Schleicher, D. Harrison

Christmas Delights 3 by RJ Scott, Kay Berrisford, Valynda King,

Make Me Yours by B. J. Wane

Colour Series Box Set by Ashleigh Giannoccaro

Hot Pursuit by Sweetland, WL

Dead Is Dead (The Jack Bertolino Series Book 3) by John Lansing

The Great Bedroom War by Laurie Kellogg

In Deep: Chase & Emma (All In Book 1) by Callie Harper