The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (12 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

10.42Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

From

The Left-Handers’ Handbook,

by J. Bliss and J. Morella.

A comparison of left-mode and right-mode characteristicsThe Left-Handers’ Handbook,

by J. Bliss and J. Morella.

Does left-handedness, then, improve a person’s ability to gain access to right-hemisphere functions such as drawing? From my observations as a teacher, I can’t say that I have noticed much difference in ease of learning to draw between left- and right-handers. Drawing came easily to me, for example, and I am extremely right-handed—though, like many people, I have some right/left confusion, perhaps indicating bilateral functions. (A person with right/left confusion is one who says “Turn left,” while pointing right.) But there is a point to be made here. The process of learning to draw creates quite a lot of mental conflict. It’s possible that left-handers are more used to that kind of conflict and are therefore better able to cope with the discomfort it creates than are fully lateralized right-handers. Clearly, much research is needed in this area.

Some art teachers recommend that right-handers shift the pencil to the left hand, presumably to have more direct access to R-mode. I do not agree. The problems with seeing that prevent individuals from being able to draw do not disappear simply by changing hands; the drawing is just more awkward. Awkwardness, I regret to say, is viewed by some art teachers as being more creative or more interesting. I think this attitude does a disservice to the student and is demeaning to art itself. We do not view awkward language, for instance, or awkward science as being more creative and somehow better.

A small percentage of students do discover by trying to draw with the left hand that they actually draw more proficiently that way. On questioning, however, it almost always comes to light that the student has some ambidexterity or was a left-hander who had been pressured to change. It would not even occur to a true right-hander like myself (or to a true left-hander) to draw with the less-used hand. But on the chance that a few of you may discover some previously hidden ambidexterity, I encourage you to try both hands at drawing, then settle on whichever hand feels the most comfortable.

Sigmund Freud, Hermann von Helmholtz, and the German poet Schiller were afflicted with right/left confusion. Freud wrote to a friend:

“I do not know whether it is obvious to other people which is their own or other’s right or left. In my case, I had to think which was my right; no organic feeling told me. To make sure which was my right hand I used quickly to make a few writing movements.”

—Sigmund Freud

The Origins of Psycho-

analysis

The Origins of Psycho-

analysis

A less august personage had the same problem:

Pooh looked at his two paws. He knew that one of them was the right, and he knew that when you had decided which one of them was the right, that the other one was the left, but he never could remember how to begin. “Well,” he said slowly . . .

—A. A. Milne

The House at Pooh Corner

The House at Pooh Corner

Psychologist Charles T. Tart, discussing alternate states of consciousness, has said, “Many meditative disciplines take the view that . . . one possesses (or can develop) an Observer that is highly objective with respect to the ordinary personality. Because it is an Observer that is essentially pure attention/awareness, it has no characteristics of its own.” Professor Tart goes on to say that some persons who feel that they have a fairly well-developed Observer “feel that this Observer can make essentially continuous observations not only within a particular d-SoC (discrete state of consciousness) but also during the transition between two or more discrete states.”

—“Putting the Pieces

Together,” 1977

Together,” 1977

In the chapters to follow, I will address the instructions to right-handers and thus avoid tedious repetition of instructions specifically for left-handers, with no intention of the “handism” that left-handers know so well.

Setting up the conditions for the L→

R shift

The exercises in the next chapter are specifically designed to cause a (hypothesized) mental shift from L-mode to R-mode. The basic assumption of the exercises is that the nature of the task can influence which mode will “take up” the job while inhibiting the other hemisphere. But the question is what factors determine which mode will predominate?

Through studies with animals, split-brain patients, and individuals with intact brains, scientists believe that the control question may be decided mainly in two ways. One way is speed: Which hemisphere gets to the job the quickest? A second way is motivation: Which hemisphere cares most or likes the task the best? And conversely: Which hemisphere cares least and likes the job the least?

Since drawing a perceived form is largely an R-mode function, it helps to reduce L-mode interference as much as possible. The problem is that the left brain is dominant and speedy and is very prone to rush in with words and symbols, even taking over jobs which it is not good at. The split brain studies indicated that dominant L-mode prefers not to relinquish tasks to its mute partner unless it really dislikes the job—either because the job takes too much time, is too detailed or slow or because the left brain is simply unable to accomplish the task. That’s exactly what we need—tasks that the dominant left brain will turn down. The exercises that follow are designed to present the brain with a task that the left hemisphere either can’t or won’t do.

And now if e’er by chance I put

My fingers into glue

Or madly squeeze a right-hand foot

Into a left-hand shoe. . . .

My fingers into glue

Or madly squeeze a right-hand foot

Into a left-hand shoe. . . .

—Lewis Carroll

Upon the Lonely Moor,

1856

Upon the Lonely Moor,

1856

4

Crossing Over: Experiencing the Shift from Left to Right

A puzzle: “If one picture is worth a thousand words, can a thousand words explicate one picture?”

—Michael Stephan

A Transformational

Theory of Aesthetics,

London: Routledge,

1990

A Transformational

Theory of Aesthetics,

London: Routledge,

1990

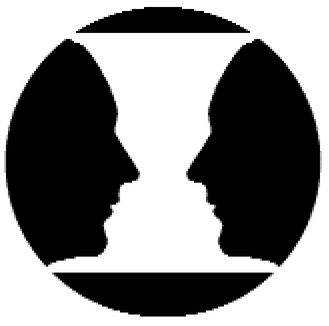

Fig. 4-1.

Vases and faces: An exercise for the double brainThe exercises that follow are specifically designed to help you understand the shift from dominant left-hemisphere mode to subdominant R-mode. I could go on describing the process over and over in words, but only you can experience for yourself this cognitive shift, this slight change in subjective state. As Fats Waller once said, “If you gotta ask what jazz is, you ain’t never gonna know.” So it is with R-mode state: You must experience the L- to R-mode shift, observe the R-mode state, and in this way come to know it. As a first step, the exercise below is designed to cause conflict between the two modes.

Following is a quick exercise designed to induce mental conflict.

What you’ll need:• Drawing paper

• Your #2 writing pencil

• Your pencil sharpener

• Your drawing board and masking tape

Figure 4-1 is a famous optical-illusion drawing, called “Vase/ Faces” because it can be seen as either:

What you’ll do:• two facing profiles or

• a symmetrical vase in the center.

Your job, of course, is to complete the second profile, which will inadvertently complete the symmetrical vase in the center.

Before you begin: Read all the directions for the exercise.

1. Copy the pattern (either Figure 4-2 or 4-3). If you are right-handed, copy the profile on the left side of the paper, facing toward the center. If you are left-handed, draw the profile on the right side, facing toward the center. Examples are shown of both the right-handed and left-handed drawings. Make up your own version of the profile if you wish.

2. Next, draw horizontal lines at the top and bottom of your profile, forming top and bottom of the vase (Figures 4-2 and 4-3).

3. Now, redraw the profile on your “Vase/Faces” pattern. Just take your pencil and go over the lines, naming the parts as you go, like this: “Forehead . . . nose . . . upper lip . . . lower lip . . . chin . . . neck.” You might even do that a second time, redrawing one more time and really thinking to yourself what those terms mean.

4. Then, go to the other side and start to draw the missing profile that will complete the symmetrical vase.

5. When you get to somewhere around the forehead or nose, you may begin perhaps to experience some confusion or conflict. Observe this as it happens.

6. The purpose of this exercise is for you to self-observe: “How do I solve the problem?”

Begin the exercise now. It should take you about five or six minutes.

Why you did this exercise:Nearly all of my students experience some confusion or conflict while doing this exercise. A few people experience a great deal of conflict, even a moment of paralysis. If this happened to you, you may have come to a point where you needed to change direction in the drawing, but didn’t know which way to go. The conflict may have been so great that you could not make your hand move the pencil to the right or the left.

That is the purpose of the exercise: to create conflict so that each person can experience in their own minds the mental “crunch” that can occur when instructions are inappropriate to the task at hand. I believe that the conflict can be explained as follows:

I gave you instructions that strongly “plugged in” the verbal system in the brain. Remember that I insisted that you name each part of the profile and I said, “Now, really think what those terms mean.”

Other books

The Vampire Bracelet: Erotic Paranormal Romance ( # 2: Blood Genies series) by Whitefeather, Sheri

Destroy All Cars by Blake Nelson

Longing by Mary Balogh

Sookie 13.5 After Dead by Charlaine Harris

A Slice of Honeybear Pie (BWWM Paranormal BBW Bear Shifter Romance) (Bearfield Book 1) by Jacqueline Sweet, Eva Wilder

Virus by S. D. Perry

The Girl With Red Hair (The Last War Saga Book 1) by Michael J Sanford

May the Farce Be With You by Roger Foss

Stare Me Down (Stare Down) by Murphy, Riley