The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (16 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

10.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

—1 Cor. 13:11

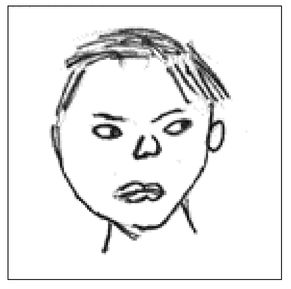

Fig. 5-1.

Fig. 5-2.

T

HE MAJORITY OF ADULTS IN THE WESTERN WORLD do not progress in art skills much beyond the level of development they reached at age nine or ten. In most mental and physical activities, individuals’ skills change and develop as they grow to adulthood: Speech is one example, handwriting another. The development of drawing skills, however, seems to halt unaccountably at an early age for most people. In our culture, children, of course, draw like children, but most adults also draw like children, no matter what level they may have achieved in other areas of life. For example, Figures 5-1 and 5-2 illustrate the persistence of childlike forms in drawings that were done recently by a brilliant young professional man who was just completing a doctoral degree at a major university.

HE MAJORITY OF ADULTS IN THE WESTERN WORLD do not progress in art skills much beyond the level of development they reached at age nine or ten. In most mental and physical activities, individuals’ skills change and develop as they grow to adulthood: Speech is one example, handwriting another. The development of drawing skills, however, seems to halt unaccountably at an early age for most people. In our culture, children, of course, draw like children, but most adults also draw like children, no matter what level they may have achieved in other areas of life. For example, Figures 5-1 and 5-2 illustrate the persistence of childlike forms in drawings that were done recently by a brilliant young professional man who was just completing a doctoral degree at a major university.

I watched the man as he did the drawings, watched him as he regarded the models, drew a bit, erased and drew again, for about twenty minutes. During this time, he became restless and seemed tense and frustrated. Later he told me that he hated his drawings and that he hated drawing, period.

If we were to attach a label to this disability in the way that educators have attached the label dyslexia to reading problems, we might call the problem dyspictoria or dysartistica or some such term. But no one has done so because drawing is not a vital skill for survival in our culture, whereas speech and reading are. Therefore, hardly anyone seems to notice that many adults draw childlike drawings and many children give up drawing at age nine or ten. These children grow up to become the adults who say that they never could draw and can’t even draw a straight line. The same adults, however, if questioned, often say that they would have liked to learn to draw well, just for their own satisfaction at solving the drawing problems that plagued them as children. But they feel that they had to stop drawing because they simply couldn’t learn how to draw.

A consequence of this early cutting off of artistic development is that fully competent and self-confident adults often become suddenly self-conscious, embarrassed, and anxious if they are asked to draw a picture of a human face or figure. In this situation, individuals often say such things as “No, I can’t! Whatever I draw is always terrible. It looks like a kid’s drawing.” Or, “I don’t like to draw. It makes me feel so stupid.” You yourself may have felt a twinge or two of those feelings when you did the Preinstruction drawings.

The crisis periodThe beginning of adolescence seems to mark the abrupt end of artistic development in terms of drawing skills for many adults. As children, they confronted an artistic crisis, a conflict between their increasingly complex perceptions of the world around them and their current level of art skills.

Most children between the ages of about nine and eleven have a passion for realistic drawing. They become sharply critical of their childhood drawings and begin to draw certain favorite subjects over and over again, attempting to perfect the image. Anything short of perfect realism may be regarded as failure.

Perhaps you can remember your own attempts at that age to make things “look right” in your drawings, and your feeling of disappointment with the results. Drawings you might have been proud of at an earlier age probably seemed hopelessly wrong and embarrassing. Looking at your drawings, you may have said, as many adolescents say, “This is terrible! I have no talent for art. I never liked it anyway, so I’m not doing it anymore.”

Children often abandon art as an expressive activity for another unfortunately frequent reason. Unthinking people sometimes make sarcastic or derogatory remarks about children’s art. The thoughtless person may be a teacher, a parent, another child, or perhaps an admired older brother or sister. Many adults have related to me their painfully clear memories of someone ridiculing their attempts at drawing. Sadly, children often blame the drawing for causing the hurt, rather than blaming the careless critic. Therefore, to protect the ego from further damage, children react defensively, and understandably so: They seldom ever attempt to draw again.

As an expert on children’s art, Miriam Lindstrom of the San Francisco Art Museum, described the adolescent art student:

“Discontented with his own accomplishments and extremely anxious to please others with his art, he tends to give up original creation and personal expression. . . . Further development of his visualizing powers and even his capacity for original thought and for relating himself through personal feelings to his environment may be blocked at this point. It is a crucial stage beyond which many adults have not advanced.”

—Miriam Lindstrom

Children’s Art,

1957

Children’s Art,

1957

“The scribblings of any . . . child clearly indicate how thoroughly immersed he is in the sensation of moving his hand and crayon aimlessly over a surface, depositing a line in his path. There must be some quantity of magic in this alone.”

—Edward Hill

The Language of Drawing,

1966

The Language of Drawing,

1966

Even sympathetic art teachers, who may feel dismayed by unfair criticism of children’s art and who want to help, become discouraged by the style of drawing that young adolescents prefer—complex, detailed scenes, labored attempts at realistic drawing, endless repetitions of favorite themes such as racing cars, and so on. Teachers recall the beguiling freedom and charm of younger children’s work and wonder what happened. They deplore what they see as “tightness” and “lack of creativity” in students’ drawings. The children themselves often become their own most unrelenting critics. Consequently, teachers frequently resort to crafts projects because they seem safer and cause less anguish—projects such as paper mosaics, string painting, drip painting, and other manipulations of materials.

As a result, most students do not learn how to draw in the early and middle grades. Their self-criticism becomes permanent, and they very rarely try to learn how to draw later in life. Like the doctoral candidate mentioned earlier, they might grow up to be highly skilled in a number of areas, but if asked to draw a human being, they will produce the same childlike image they were drawing at age ten.

From infancy to adolescenceFor most of my students, it has proved beneficial to go back in time to try to understand how their visual imagery in drawing developed from infancy to adolescence. With a firm grasp on how the symbol system of childhood drawing has developed, students seem to “unstick” their artistic development more easily in order to move on to adult skills.

The scribbling stageMaking marks on paper begins at about age one and a half, when you as an infant were given a pencil or crayon, and you, by yourself, made a mark. It’s hard for us to imagine the sense of wonder a child experiences on seeing a black line emerge from the end of a stick, a line the child controls. You and I, all of us, had that experience.

After a tentative start, you probably scribbled with delight on every available surface, perhaps including your parents’ best books and the walls of a bedroom or two. Your scribbles were seemingly quite random at first, like the example in Figure 5-3, but very quickly began to take on definite shapes. One of the basic scribbling movements is a circular one, probably arising simply from the way the shoulder, arm, wrist, hand, and fingers work together. A circular movement is a natural movement—more so, for instance, than the arm movements required to draw a square. (Try both on a piece of paper, and you’ll see what I mean.)

The stage of symbolsAfter some days or weeks of scribbling, infants—and apparently all human children—make the basic discovery of art: A drawn symbol can stand for something out there in the environment. The child makes a circular mark, looks at it, adds two marks for eyes, points to the drawing, and says, “Mommy,” or “Daddy,” or “That’s me,” or “My dog,” or whatever. Thus, we all made the uniquely human leap of insight that is the foundation for art, from the prehistoric cave paintings all the way up through the centuries to the art of Leonardo, Rembrandt, and Picasso.

With great delight, infants draw circles with eyes, mouth, and lines sticking out to represent arms and legs, as in Figure 5-4. This form, a symmetrical, circular form, is a basic form universally drawn by infants. The circular form can be used for almost anything: With slight variations, the basic pattern can stand for a human being, a cat, a sun, a jellyfish, an elephant, a crocodile, a flower, or a germ. For you as a child, the picture was whatever you said it was, although you probably made subtle and charming adjustments of the basic form to get the idea across.

By the time children are about three and a half, the imagery of their art becomes more complex, reflecting growing awareness and perceptions of the world. A body is attached to the head, though it may be smaller than the head. Arms may still grow out of the head, but more often they emerge from the body—sometimes from below the waist. Legs are attached to the body.

Fig. 5-3. Scribble drawing by a two-and-a-half-year-old.

Fig. 5-4. Figure-image drawing by a three-and-a-half-year-old.

Children’s repeated images become known to fellow students and teachers, as shown in this wonderful cartoon by Brenda Burbank.

Other books

The Beast by Lindsay Mead

The Baseball Economist: The Real Game Exposed by Bradbury, J.C.

The Sorrow of War by Bao Ninh

Eden Hill by Bill Higgs

Trueish Crime: A Kat Makris Greek Mafia Novel by Alex A. King

Street Safe by W. Lynn Chantale

Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? by Andrew Lawler

The True Prince by J.B. Cheaney

Destination India by Katy Colins

Malediction: An Old World Story by Melissa F. Olson