The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (18 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

11.47Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The stage of complexity

Now, like the ghosts in Dickens’s

A Christmas Carol,

we’ll move you on to observe yourself at a slightly later age, at nine or ten. Possibly you may remember some of the drawings you did at that age—in the fifth, sixth, or seventh grade.

A Christmas Carol,

we’ll move you on to observe yourself at a slightly later age, at nine or ten. Possibly you may remember some of the drawings you did at that age—in the fifth, sixth, or seventh grade.

During this period, children try for more detail in their artwork, hoping by this means to achieve greater realism, which is a prized goal. Concern for composition diminishes, the forms often being placed almost at random on the page. Seemingly, children’s concern for where things are in the drawing is replaced with concern for how things look, particularly the details of forms. Overall, drawings by older children show greater complexity and, at the same time, less assurance than do the landscapes of early childhood.

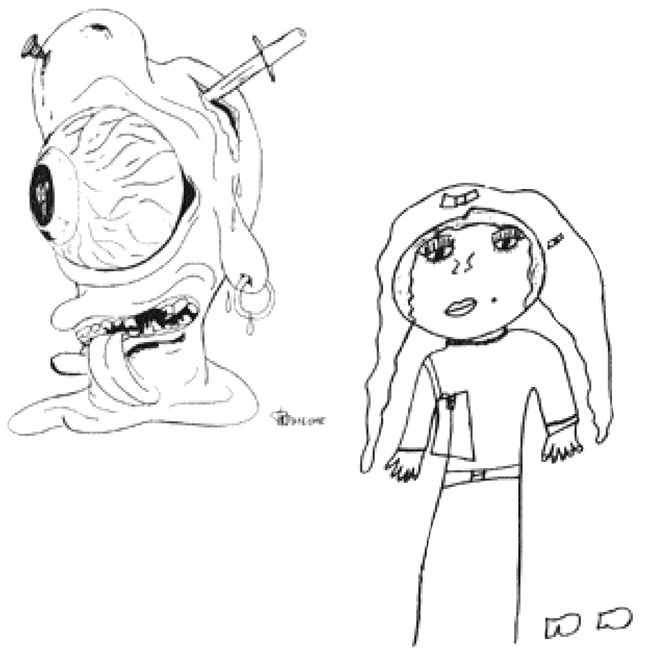

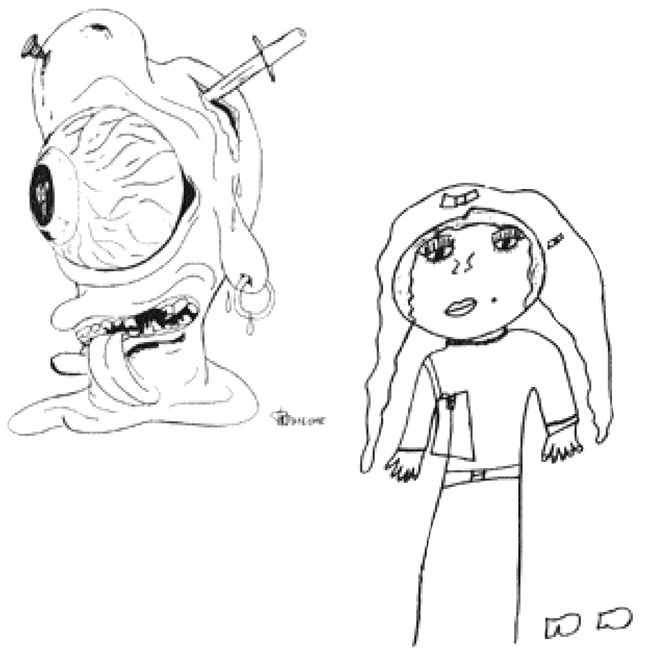

Also around this time, children’s drawings become differentiated by sex, probably because of cultural factors. Boys begin to draw automobiles—hot rods and racing cars; war scenes with dive bombers, submarines, tanks, and rockets. They draw legendary figures and heroes—bearded pirates, Viking crewmen and their ships, television stars, mountain climbers, and deep-sea divers. They are fascinated by block letters, especially monograms; and some odd images such as (my favorite) an eyeball complete with piercing dagger and pools of blood.

Fig. 5-9.

Fig. 5-10.

Children seem to start out with a nearly perfect sense of composition, which they often lose during adolescence and regain only through laborious study. I believe that the reason may be that older children concentrate their perceptions on separate objects existing in an undifferentiated space, whereas young children construct a self-contained conceptual world bounded by the paper’s edges. For older children, however, the edges of the paper seem almost nonexistent, just as edges are nonexistent in open, real space.

Meanwhile, girls are drawing tamer things—flowers in vases, waterfalls, mountains reflected in still lakes, pretty girls running or sitting on the grass, fashion models with incredible eyelashes, elaborate hairstyles, tiny waists and feet, and hands held behind the back because hands are “hard to draw.”

Figures 5-11 through 5-14 are some examples of these early adolescent drawings. I’ve included a cartoon drawing: Cartoons are drawn by both boys and girls and are much admired. I believe that cartooning appeals to children at this age because cartoons employ familiar symbolic forms but are used in a more sophisticated way, thus enabling adolescents to avoid feeling that their drawing is “babyish.”

Fig. 5-11. Gruesome eyeballs are a favorite theme of adolescent boys. Meanwhile, girls are drawing tamer subjects such as this bride.

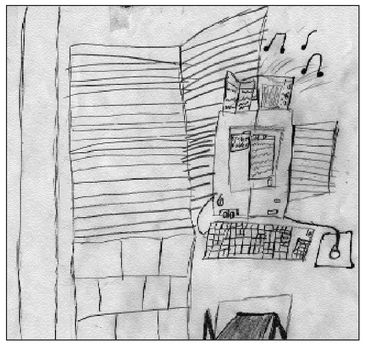

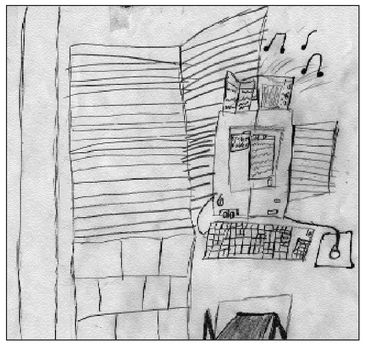

Fig. 5-12. Complex drawing by Naveen Molloy, then ten years old. This is an example of the kind of drawing by adolescents that teachers often deplore as “tight” and uncreative. Young artists work very hard to perfect images like this one of electronic equipment. Note the keyboard and mouse. The child will soon reject this image, however, as hopelessly inadequate.

Fig. 5-13. Complex drawing by a nine-year-old girl. Transparency is a recurrent theme in the drawings of children at this stage. Things seen under water, through glass windows, or in transparent vases—as in this drawing—are all favorite themes. Though one could guess at a psychological meaning, it is quite likely that young artists are simply trying this idea to see if they can make the drawings “look right.”

Fig. 5-14. Complex drawing by a ten-year-old boy. Cartooning is a favorite form of art in the early adolescent years. As art educator Miriam Lindstrom notes in

Children’s Art,

the level of taste at this age is at an all-time low.

The stage of realismChildren’s Art,

the level of taste at this age is at an all-time low.

By around age ten or eleven, children’s passion for realism is in full bloom (Figures 5-15 and 5-16). When their drawings don’t come out “right”—meaning that they don’t look realistic—children often become discouraged and ask their teachers for help. The teacher may say, “You must look more carefully,” but this doesn’t help, because the child doesn’t know what to look more carefully for. Let me illustrate that with an example.

Fig. 5-15. Realistic drawing by a twelve-year-old. Children aged ten to twelve are searching for ways to make things “look real.” Figure drawing in particular fascinates adolescents. In this drawing, symbols from an earlier stage are fitted into new perceptions: Note the front-view eye in this profile drawing. Note also that the child’s knowledge of the chair back has been substituted for the purely visual appearance of the back of the chair seen from the side.

Fig. 5-16. Realistic drawing by a twelve-year-old. At this stage, children’s main effort is toward achieving realism. Awareness of the edges of the drawing surface fades and attention is concentrated on individual, unrelated forms randomly distributed about the page. Each segment functions as an individual element without regard for unified composition.

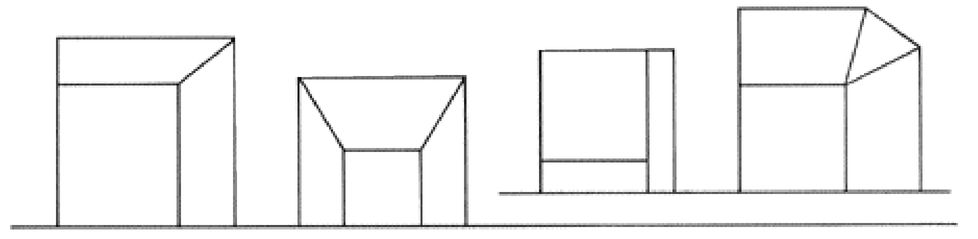

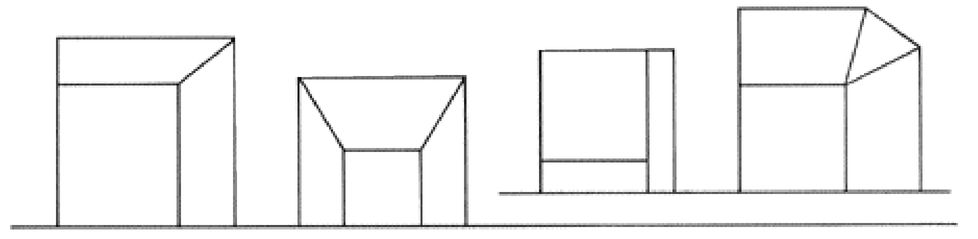

Say that a ten-year-old wants to draw a picture of a cube, perhaps a three-dimensional block of wood. Wanting the drawing to look “real,” the child tries to draw the cube from an angle that shows two or three planes—not just a straight-on side view that would show only a single plane, and thus would not reveal the true shape of the cube.

To do this, the child must draw the oddly angled shapes just as they appear—that is, just like the image that falls on the retina of the perceiving eye. Those shapes are not square. In fact, the child must suppress knowing that the cube is square and draw shapes that are “funny.” The drawn cube will look like a cube only if it is comprised of oddly angled shapes. Put another way, the child must draw unsquare shapes to draw a square cube. The child must accept this paradox, this illogical process, which conflicts with verbal, conceptual knowledge. (Perhaps this is one meaning of Picasso’s statement that “Painting is a lie that tells the truth.”)

Other books

Surrender: Ultra Alpha Age Play ABDL Romance by D.D. Wyatt

Sorority Girls With Guns by Cat Caruthers

Essex Boy: My Story by Kirk Norcross

Ashes of the Realm - Greyson's Revenge by Saxon Andrew, Derek Chido

McNally's Secret by Lawrence Sanders

Dark Rival by Brenda Joyce

The Almost Wives Club: Kate by Nancy Warren

How To Rape A Straight Guy by Sullivan, Kyle Michel

Very in Pieces by Megan Frazer Blakemore

Amanda Scott - [Dangerous 04] by Dangerous Lady