The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (14 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

5.98Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Fig. 4-5. In copying signatures, forgers turn the originals upside down to see the exact shapes of the letters more clearly—to see, in fact, in the artist’s mode.

Fig. 4-6. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770),

The Death of Seneca.

Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago, Joseph and Helen Regenstein Collection.

The Death of Seneca.

Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago, Joseph and Helen Regenstein Collection.

Photograph by Philippe Halsman, 1947. © Yvonne Halsman, 1989. This is the full photograph shown upside down on the page 56. We are indebted to Yvonne Halsman for allowing this unorthodox presentation of Philippe Halsman’s famous image of Einstein.

2. You may start anywhere you wish—bottom, either side, or the top. Most people tend to start at the top. Try not to figure out what you are looking at in the upside-down image. It is better not to know. Simply start copying the lines. But remember: don’t turn the drawing right side up!

Fig. 4-7. Pablo Picasso (1881-1973),

Portrait of Igor Stravinsky.

Paris, May 21, 1920 (dated). Privately owned.

Portrait of Igor Stravinsky.

Paris, May 21, 1920 (dated). Privately owned.

3. I recommend that you not try to draw the entire outline of the form and then “fill in” the parts. The reason is that if you make any small error in the outline, the parts inside won’t fit. One of the great joys of drawing is the discovery of how the parts fit together. Therefore, I recommend that you move from line to adjacent line, space to adjacent shape, working your way through the drawing, fitting the parts together as you go.

4. If you talk to yourself at all, use only the language of vision, such as: “This line bends this way,” or, “That shape has a curve there,” or “Compared to the edge of the paper (vertical or horizontal), this line angles like that,” and so on. What you do not want to do is to name the parts.

5. When you come to parts that seem to force their names on you—the H-A-N-D-S and the F-A-C-E—try to focus on these parts just as shapes. You might even cover up with one hand or finger all but the specific line you are drawing and then uncover each adjacent line. Alternatively, you might shift to another part of the drawing.

6. At some point, the drawing may begin to seem like an interesting, even fascinating, puzzle. When this happens, you will be “really drawing,” meaning that you have successfully shifted to R-mode and you are seeing clearly. This state is easily broken. For example, if someone were to come into the room and ask, “How are you doing?” your verbal system would be reactivated and your focus and concentration would be over.

7. You may even want to cover most of the reproduced drawing with another piece of paper, slowly uncovering new areas as you work your way down through the drawing. A note of caution, however: Some of my students find this ploy helpful, while some find it distracting and unhelpful.

8. Remember that everything you need to know in order to draw the image is right in front of your eyes. All of the information is right there, making it easy for you. Don’t make it complicated. It really is as simple as that.

Begin your Upside-Down Drawing now.

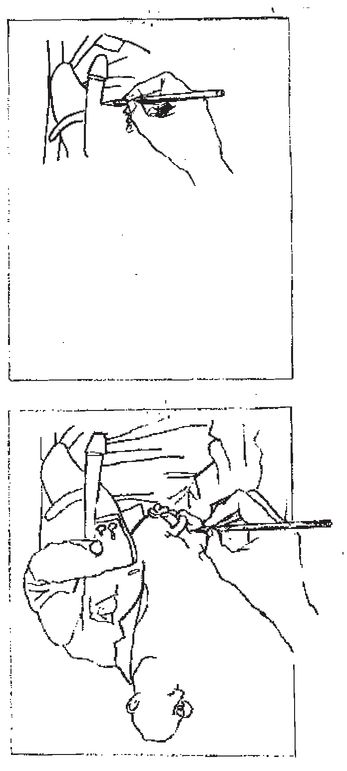

Figs. 4-8, 4-9. Inverted drawing. Forcing the cognitive shift from the dominant left-hemisphere mode to the subdominant right-hemisphere mode.

Fig. 4-10. “I Want You for U. S. Army” by James Montgomery Flagg, 1917 poster. Permission: Trustees of the Imperial War Museum, London, England.

Uncle Sam’s arm and hand are “foreshortened” in this Army poster. Foreshortening is an art term. It means that, in order to give the illusion of forms advancing or receding in space, the forms must be drawn just as they appear in that position, not depicting what we know about their actual length. Learning to “foreshorten” is often difficult for beginners in drawing.

Turn both of the drawings—the reproduction in the book and your copy—right side up. I can confidently predict that you will be pleased with your drawing, especially if you have thought in the past that you would never be able to draw.

I can also confidently predict that the most “difficult” parts, the “foreshortened” areas, are beautifully drawn, creating a spatial illusion.

Yet, see what you have accomplished, drawing upside down. If you used Picasso’s drawing of Igor Stravinsky seated in a chair, you drew the crossed legs beautifully in foreshortened view. For most of my students, this is the finest part of their drawing, despite the foreshortening. How could they draw this “difficult” part so well? Because they didn’t know what they were drawing! They simply drew what they saw, just as they saw it—one of the most important keys to drawing well. The same applies to the foreshortened horse in the German drawing, Figure 4-13.

A logical box for L-modeFigure 4-11 and Figure 4-12 show two drawings by the same university student. This student had misunderstood my instructions to the class and did the drawing right side up. When he came to class the next day, he showed me his drawing and said, “I misunderstood. I just drew it the regular way.” I asked him to do another drawing, this time upside down. He did, and Fig. 4-12 was the result.

It goes against common sense that the upside-down drawing is so far superior to the drawing done right side up. The student himself was astonished.

Fig. 4-11; near right: The Picasso drawing mistakenly copied right side up by a university student.

Other books

Through the Eye of Time by Trevor Hoyle

The Golden Shield of IBF by Jerry Ahern, Sharon Ahern

Hold Me: Delos Series, 5B1 by Lindsay McKenna

Early Graves by Joseph Hansen

Learning to Trust Part 1 by B. B. Roman

Sector General Omnibus 3 - General Practice by James White

Black Parade by Jacqueline Druga

Hidden Threat by Sherri Hayes

Thimble Summer by Elizabeth Enright

At the City's Edge by Marcus Sakey