The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (13 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

2.25Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

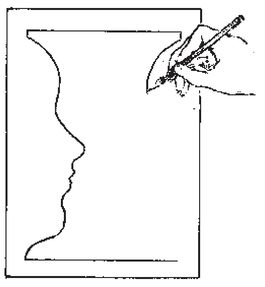

Fig. 4-2. For left-handers.

Fig. 4-3. For right-handers.

By the way, I must mention that the eraser is just as important a tool for drawing as the pencil. I’m not exactly sure where the notion “erasing is bad” came from. The eraser allows you to correct your drawings. My students certainly see me erasing when I do demonstration drawings in our workshops.

Then, I gave you a task (to complete the second profile and, simultaneously, the vase) that can only be done by shifting to the visual, spatial mode of the brain. This is the part of the brain that can perceive and nonverbally assess relationship of sizes, curves, angles, and shapes.

The difficulty of making that mental shift causes a feeling of conflict and confusion—and even a momentary mental paralysis.

You may have found a way to solve the problem, thereby enabling yourself to complete the second profile and therefore the symmetrical vase.

How did you solve it?

• By deciding not to think of the names of the features?

• By shifting your focus from the face-shapes to the vase-shapes?

• By using a grid (drawing vertical and horizontal lines to help you see relationships)? Or perhaps by marking points where the outermost and innermost curves occurred?

• By drawing from the bottom up rather than from the top down?

• By deciding that you didn’t care whether the vase was symmetrical or not and drawing any old memorized profile just to finish with the exercise? (With this last decision, the verbal system “won” and the visual system “lost.”)

Let me ask you a few more questions. Did you use your eraser to “fix up” your drawing? If so, did you feel guilty? If so, why? (The verbal system has a set of memorized rules, one of which may be, “You can’t use an eraser unless the teacher says it’s okay.”) The visual system, which is largely without language, just keeps looking for ways to solve the problem according to another kind of logic—visual logic.

To sum up, the point of the seemingly simple “Vase/Faces” exercise is this:

In order to draw a perceived object or person—something that you see with your eyes—you must make a mental shift to a brain-mode that is specialized for this visual, perceptual task.

The difficulty of making this shift from verbal to visual mode often causes conflict. Didn’t you feel it? To reduce the discomfort of the conflict, you stopped (do you remember feeling stopped short?) and made a new start. That’s what you were doing when you gave yourself instructions—that is, gave your brain instructions—to “shift gears,” or “change strategy,” or “don’t do this; do that,” or whatever terms you may have used to cause a cognitive shift.

There are numerous solutions to the mental “crunch” of the “Vase/Faces” Exercise. Perhaps you found a unique or unusual solution. To capture your personal solution in words, you might want to write down what happened on the back of your drawing.

Thomas Gladwin, an anthropologist, contrasted the ways that a European and a native Trukese sailor navigated small boats between tiny islands in the vast Pacific Ocean.

Before setting sail, the European begins with a plan that can be written in terms of directions, degrees of longitude and latitude, estimated time of arrival at separate points on the journey. Once the plan is conceived and completed, the sailor has only to carry out each step consecutively, one after another, to be assured of arriving on time at the planned destination. The sailor uses all available tools, such as a compass, a sextant, a map, etc., and if asked, can describe exactly how he got where he was going.

The European navigator uses the left-hemisphere mode.

In contrast, the native Trukese sailor starts his voyage by

imaging the position

of his destination

relative to the position

of other islands. As he sails along, he constantly adjusts his direction according to his awareness of his position

thus far.

His decisions are improvised continually by checking relative positions of landmarks, sun, wind direction, etc. He navigates with reference to where he started, where he is going, and the space between his destination and the point

where he is at the moment.

If asked how he navigates so well without instruments or a written plan, he cannot possibly put it into words. This is not because the Trukese are unaccustomed to describing things in words, but rather because the process is too complex and fluid to be put into words.

imaging the position

of his destination

relative to the position

of other islands. As he sails along, he constantly adjusts his direction according to his awareness of his position

thus far.

His decisions are improvised continually by checking relative positions of landmarks, sun, wind direction, etc. He navigates with reference to where he started, where he is going, and the space between his destination and the point

where he is at the moment.

If asked how he navigates so well without instruments or a written plan, he cannot possibly put it into words. This is not because the Trukese are unaccustomed to describing things in words, but rather because the process is too complex and fluid to be put into words.

The Trukese navigator uses the right-hemisphere mode.

—J. A. Paredes and M. J. Hepburn

“The Split-Brain and the Culture-

Cognition Paradox,” 1976

“The Split-Brain and the Culture-

Cognition Paradox,” 1976

Charles Tart, professor of psychology at the University of California, Davis, states: “We begin with a concept of some kind of basic

awareness,

some kind of basic ability to ‘know’ or ‘sense’ or ‘cognize’ or ‘recognize’ that something is happening. This is a fundamental theoretical and experiential given. We do not know scientifically what the ultimate nature of awareness is, but it is our starting point.”

awareness,

some kind of basic ability to ‘know’ or ‘sense’ or ‘cognize’ or ‘recognize’ that something is happening. This is a fundamental theoretical and experiential given. We do not know scientifically what the ultimate nature of awareness is, but it is our starting point.”

—Charles T. Tart

Alternate States of

Consciousness,

1975

Alternate States of

Consciousness,

1975

When you did your drawing of the Vase/Faces, you drew the first profile in the left-hemisphere mode, like the European navigator, taking one part at a time and naming the parts one by one. The second profile was drawn in the right-hemisphere mode. Like the navigator from the South Sea Island of Truk, you constantly scanned to adjust the direction of the line. You probably found that naming the parts such as forehead, nose, or mouth seemed to confuse you. It was better not to think of the drawing as a face. It was easier to use the shape of the space between the two profiles as your guide. Stated differently, it was easiest not to think at all—that is, in words. In right-hemisphere-mode drawing, the mode of the artist, if you do use words to think, ask yourself only such things as:

“Where does that curve start?”

“How deep is that curve?”

“What is that angle relative to the edge of the paper?”

“How long is that line relative to the one I’ve just drawn?”

“Where is that point as I scan across to the other side—where is that point relative to the distance from the top (or bottom) edge of the paper?”

These are R-mode questions: spatial, relational, and comparative. Notice that no parts are named. No statements are made, no conclusions drawn, such as, “The chin must come out as far as the nose,” or “Noses are curved.”

A brief review: What is learned in “learning to draw”?Realistic drawing of a perceived image requires the visual mode of the brain, most often mainly located in the right hemisphere. This visual mode of thinking is fundamentally different from the brain’s verbal system—the one we largely rely on nearly all of our waking hours.

For most tasks, the two modes are combined. Drawing a perceived object or person may be one of the few tasks that requires mainly one mode: the visual mode largely unassisted by the verbal mode. There are other examples. Athletes and dancers, for instance, seem to perform best by quieting the verbal system during performances. Moreover, a person who needs to shift in the other direction, from visual to verbal mode, can also experience conflict. A surgeon once told me that while operating on a patient (mainly a visual task, once a surgeon has acquired the knowledge and experience needed) he would find himself unable to name the instruments. He would hear himself saying to an attendant, “Give me the . . . the . . . you know, the . . . thingamajig!”

Learning to draw, therefore, turns out not to be “learning to draw.” Paradoxically, learning to draw means learning to access at will that system in the brain that is the appropriate one for drawing. Putting it another way, accessing the visual mode of the brain—the appropriate mode for drawing—causes you to see in the special way an artist sees. The artist’s way of seeing is different from ordinary seeing and requires an ability to make mental shifts at conscious level. Put another way and perhaps more accurately, the artist is able to set up conditions that cause a cognitive shift to “happen.” That is what a person trained in drawing does, and that is what you are about to learn.

Again, this ability to see things differently has many uses in life aside from drawing—not the least of which is creative problem solving.

Keeping the “Vase/Faces” lesson in mind, then, try the next exercise, one that I designed to reduce conflict between the two brain-modes. The purpose of this exercise is just the reverse of the previous one.

Upside-down drawing: Making the shift to R-modeFamiliar things do not look the same when they are upside down. We automatically assign a top, a bottom, and sides to the things we perceive, and we expect to see things oriented in the usual way—that is, right side up. For, in upright orientation, we can recognize familiar things, name them, and categorize them by matching what we see with our stored memories and concepts.

When an image is upside down, the visual clues don’t match.

“The object of painting a picture is not to make a picture—however unreasonable that may sound . . . The object, which is back of every true work of art, is the attainment of a

state of being

[Henri’s emphasis], a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. [The picture] is but a by-product of the state, a trace, the footprint of the state.”

state of being

[Henri’s emphasis], a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. [The picture] is but a by-product of the state, a trace, the footprint of the state.”

From

The Art Spirit

by American artist and teacher Robert Henri, B. Lippincott Company, 1923.

The Art Spirit

by American artist and teacher Robert Henri, B. Lippincott Company, 1923.

The message is strange, and the brain becomes confused. We see the shapes and the areas of light and shadow. We don’t particularly object to looking at upside-down pictures unless we are called on to name the image. Then the task becomes exasperating.

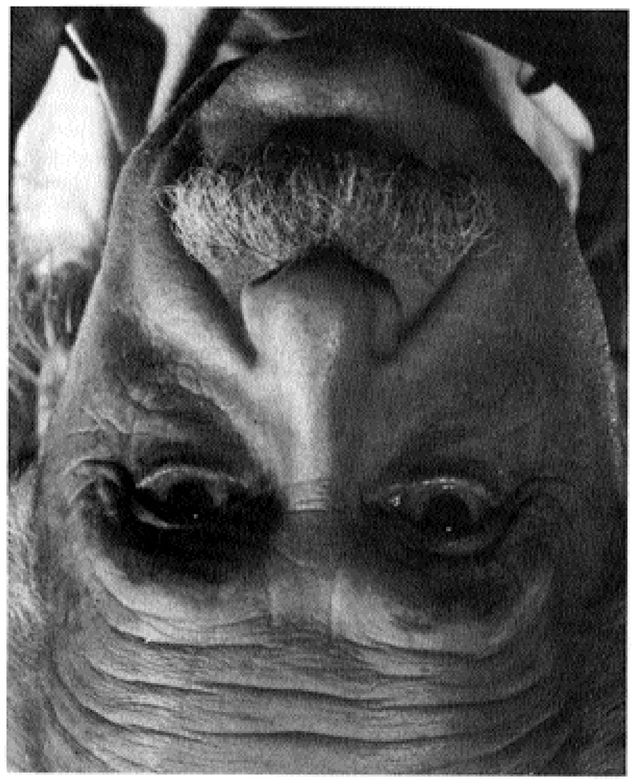

Seen upside down, even well-known faces are difficult to recognize and name. For example, the photograph in Figure 4-4 is of a famous person. Do you recognize who it is?

You may have had to turn the photograph right side up to see that it is Albert Einstein, the famous scientist. Even after you know who the person is, the upside-down image probably continues to look strange.

Fig. 4-4. Photograph by Philippe Halsman.

Inverted orientation causes recognition problems with other images (see Figure 4-5). Your own handwriting, turned upside down, is probably difficult for you to figure out, although you’ve been reading it for years. To test this, find an old shopping list or letter in your handwriting and try to read it upside down.

A complex drawing, such as the one shown upside down in the Tiepolo drawing, Figure 4-6, is almost indecipherable. The (left) mind just gives up on it.

Upside-down drawingAn exercise that reduces mental conflict

We shall use this gap in the abilities of the left hemisphere to allow R-mode to have a chance to take over for a while.

Figure 4-7 is a reproduction of a line drawing by Picasso of the composer Igor Stravinsky. The image is upside down. You will be copying the upside-down image. Your drawing, therefore, will be done also upside down. In other words, you will copy the Picasso drawing just as you see it. See Figures 4-8 and 4-9.

What you’ll need:• The reproduction of the Picasso drawing, Fig. 4-7, p. 58.

• Your #2 writing pencil, sharpened.

• Your drawing board and masking tape.

• Forty minutes to an hour of uninterrupted time.

Before you begin: Read all of the following instructions.

1. Play music if you like. As you shift into R-mode, you may find that the music fades out. Finish the drawing in one sitting, allowing yourself at least forty minutes—more if possible. And more important, do not turn the drawing right side up until you have finished. Turning the drawing would cause a shift back to L-mode, which we want to avoid while you are learning to experience the focused R-mode state of awareness.

Other books

Kill List (Special Ops #8) by Capri Montgomery

Something Going Around by Harry Turtledove

The Apprentice by Gerritsen Tess

FITNESS CONFIDENTIAL by Tortorich, Vinnie, Lorey, Dean

Tamed: A Kinky Adult Fairy Tale (Bedding the Bad Girl Book 2) by Wild, Callie

ShamrockDelight by Maxwell Avoi

Indigo Sky by Ingis, Gail

Apocalypse Cult (Gray Spear Society) by Alex Siegel

Hiding From Death (A Darcy Sweet Cozy Mystery #6) by Emrick, K.J.