The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (8 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

7.57Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Heather

by instructor Brian Bomeisler.

by instructor Brian Bomeisler.

Heather

by the author.

by the author.

Because the exercises in this book focus on expanding your

perceptual

powers, not on techniques of drawing, your individual style—your unique and valuable manner of drawing—will emerge intact. This is true even though the exercises concentrate on realistic drawings, which tend to “look alike” in a large sense. (This probably is true only for this century, because we are used to seeing radically different forms of art, both stylistically and culturally.) But a closer look at realistic art reveals subtle differences in line style, emphasis, and intent. In this age of massive self-expression in the arts, this more subtle communication often goes unnoticed and unappreciated.

perceptual

powers, not on techniques of drawing, your individual style—your unique and valuable manner of drawing—will emerge intact. This is true even though the exercises concentrate on realistic drawings, which tend to “look alike” in a large sense. (This probably is true only for this century, because we are used to seeing radically different forms of art, both stylistically and culturally.) But a closer look at realistic art reveals subtle differences in line style, emphasis, and intent. In this age of massive self-expression in the arts, this more subtle communication often goes unnoticed and unappreciated.

As your skills in seeing increase, your ability to draw what you see will increase, and you will observe your style forming. Guard it, nurture it, and cherish it, for your style expresses you. As with the Zen master-archer, the target is yourself.

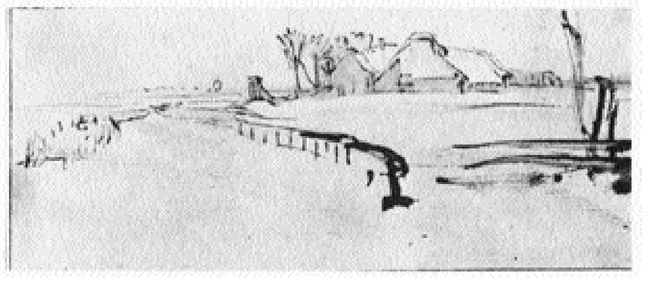

Fig. 2-2. Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-1669),

Winter Landscape

(c. 1649). Courtesy of The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University.

Winter Landscape

(c. 1649). Courtesy of The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University.

Rembrandt drew this tiny landscape with a rapid calligraphic line. Through it, we sense Rembrandt’s visual and emotional response to the deeply silent winter scene. We see, therefore, not only the landscape; we see

through

the landscape to Rembrandt himself.

through

the landscape to Rembrandt himself.

Artists are known by their unique line qualities, and experts in drawing often base their authentication of drawings on these known line qualities. Styles of line have actually been put into named categories. There are quite a few: the “bold line;” the “broken line”

(sometimes called “the line that repeats itself”); the “pure line”—thin and precise, sometimes called “the Ingres line” after the 19th century French artist Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres; the “lost-and-found line,” which starts out dark, fades away, then becomes dark again. See samples in figure 2-3.

Beginning students most often admire drawings done in a rapid, self-confident style—the “bold” line that is rather like Picasso’s, in fact. But an important point to remember is that

every style of line is valued, one not more than another.

every style of line is valued, one not more than another.

Fig. 2-3.

3

Your Brain: The Right and Left of It

“Few people realize what an astonishing achievement it is to be able to see at all. The main contribution of the new field of artificial intelligence has been not so much to solve these problems of information handling as to show what tremendously difficult problems they are. When one reflects on the number of computations that must have to be carried out before one can recognize even such an everyday scene as another person crossing the street, one is left with a feeling of amazement that such an extraordinary series of detailed operations can be accomplished so effortlessly in such a short space of time.”

F. H. C. Crick, “Thinking about the Brain,” in

The Brain,

San Francisco: A Scientific American Book, W. H. Freeman, 1979, p. 130.

The Brain,

San Francisco: A Scientific American Book, W. H. Freeman, 1979, p. 130.

H

OW DOES THE HUMAN BRAIN WORK? That remains the most baffling and elusive of all questions having to do with human understanding. Despite centuries of study and thought and the accelerating rate of knowledge in recent years, the brain still engenders awe and wonder at its marvelous capabilities—many of which we simply take for granted.

OW DOES THE HUMAN BRAIN WORK? That remains the most baffling and elusive of all questions having to do with human understanding. Despite centuries of study and thought and the accelerating rate of knowledge in recent years, the brain still engenders awe and wonder at its marvelous capabilities—many of which we simply take for granted.

Scientists have targeted visual perception in particular with highly precise studies, and yet vast mysteries still exist. The most ordinary activities are awe-inspiring. For example, in a recent contest, people were shown a photograph of six mothers and their six children, arranged randomly in a group. Contestants, strangers to the photographed group, were asked to link the six mother-and-child pairs. Forty people responded, and each had paired all of the mothers and children correctly.

To think of the complexity of that task is to make one’s head spin. Our faces are more alike than unlike: two eyes, a nose, a mouth, hair, and two ears, all more or less the same size and in the same places on our heads. Telling two people apart requires fine discriminations beyond the capability of nearly all computers, as I mentioned in the Introduction. In this contest, participants had to distinguish each adult from all the others and estimate, using even finer discriminations, which child’s features/head-shape /expression best fitted with which adult. The fact that people can accomplish this astounding feat and not realize how astounding it is forms, I think, a measure of our underestimation of our visual abilities.

Another extraordinary activity is drawing. As far as we know, of all the creatures on this planet, human beings are the only ones who draw images of things and persons in their environment. Monkeys and elephants have been persuaded to paint and draw and their artworks have been exhibited and sold. And, indeed, these works do seem to have expressive content, but they are never realistic images of the animals’ perceptions. Animals do not do still-life, landscape, or portrait drawing. So unless there is some monkey that we don’t know about out there in the forest drawing pictures of other monkeys, we can assume that drawing perceived images is an activity confined to human beings and made possible by our human brain.

Both sides of your brainSeen from above, the human brain resembles the halves of a walnut—two similar appearing, convoluted, rounded halves connected at the center (Figure 3-1). The two halves are called the “left hemisphere” and the “right hemisphere.”

The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body; the right hemisphere controls the left side. If you suffer a stroke or accidental brain damage to the left half of your brain, for example, the right half of your body will be most seriously affected and vice versa. As part of this crossing over of the nerve pathways, the left hand is controlled by the right hemisphere; the right hand, by the left hemisphere, as shown in Figure 3-2.

Fig. 3-1.

The double brainWith the exception of human beings and possibly songbirds, the greater apes, and certain other mammals, the cerebral hemispheres (the two halves of the brain) of Earth’s creatures are essentially alike, or symmetrical, both in appearance and in function. Human cerebral hemispheres, and those of the exceptions noted above, develop asymmetrically in terms of function. The most noticeable outward effect of the asymmetry of the human brain is handedness, which seems to be unique to human beings and possibly chimpanzees.

Fig. 3-2. The crossover connections of left hand to right hemisphere, right hand to left hemisphere.

For the past two hundred years or so, scientists have known that language and language-related capabilities are mainly located in the left hemispheres of the majority of individuals—approximately 98 percent of right-handers and about two-thirds of left-handers. Knowledge that the left half of the brain is specialized for language functions was largely derived from observations of the effects of brain injuries. It was apparent, for example, that an injury to the left side of the brain was more likely to cause a loss of speech capability than an injury of equal severity to the right side.

Other books

Terr5tory by Susan Bliler

Lamb by Christopher Moore

Once by Alice Walker

The Huckleberry Murders: A Sheriff Bo Tully Mystery by Patrick F. McManus

Finding Monsters by Liss Thomas

21 Pounds in 21 Days by Roni DeLuz

Gone Cold by Douglas Corleone

Un lugar llamado libertad by Ken Follett

Student by David Belbin

From the Beginning: The Old World by Kurtz, Timna