The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (7 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

11.09Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The symbol system of childhood

This “tyranny” of the symbol system explains in large part why people untrained in drawing continue to produce “childish” drawings right into adulthood and even old age. What you will learn from me is how to set your symbol system aside and accurately draw what you see. This training in perceptual skills is the rockbottom “ABC” of drawing, necessarily—or at least ideally—learned before progressing to imaginative drawing, painting, and sculpture.

With this information about the symbol system in mind, you may want to add a few more notes on the back of your drawings. Then, put all three drawings away for safekeeping. Do not look at them again until after you have completed my course and have learned to see and draw.

Student showing: A preview of before-and-after drawingsNow I would like to show you some drawings done by my students. The drawings show typical changes in students’ drawing ability from the first lesson (before instruction) to the last lesson. Most of these students attended five-day workshops, eight hours a day for the five days. Both the Pre-instruction and Post-instruction drawings are self-portraits, drawn by students observing their own images in mirrors. As you can see, the Before-and-After drawings in the student examples demonstrate that the students have transformed their ways of seeing and drawing. The changes are significant enough that it almost seems as though two different persons have done the drawings.

The drawings on this page and the following page show Before-and-After drawings of an entire five-day class, held in Seattle, August 4, 1997, to August 8, 1997.

Drawings from the five-day Seattle class, continued.

Learning to perceive

is the basic skill that the students acquired. The change you see in their ability to draw possibly reflects an equally significant change in their ability to see. Regard the drawings from that standpoint: as a visible record of the students’ improvement in perceptual skills.

is the basic skill that the students acquired. The change you see in their ability to draw possibly reflects an equally significant change in their ability to see. Regard the drawings from that standpoint: as a visible record of the students’ improvement in perceptual skills.

On pages 19-20 I present Before-and-After drawings by an entire class, a group of adult students in Seattle, Washington. Looking at the “Before” drawings, you will see that students came to the five-day class with different levels of existing drawing skills and backgrounds in art. The “After” drawings, done five days later, however, show a remarkably consistent high level of skills. This overall success rate, I believe, demonstrates our goal with every group: that every student will gain high-level drawing skills regardless of their existing (or non-existing) skill level.

Expressing yourself in drawing: The nonverbal language of artThe purpose of this book is to teach you basic skills in seeing and drawing. The purpose of this book is

not

to teach you to express yourself, but instead to provide you with the skills that will

release

you from stereotypic expression. This release in turn will open the way for you to express your individuality—your essential uniqueness—

in your own way,

using your own particular drawing style.

not

to teach you to express yourself, but instead to provide you with the skills that will

release

you from stereotypic expression. This release in turn will open the way for you to express your individuality—your essential uniqueness—

in your own way,

using your own particular drawing style.

If, for a moment, we could regard your handwriting as a form of expressive drawing, we could say that you are already expressing yourself with a fundamental element of art: line.

“The art of archery is not an athletic ability mastered more or less through primarily physical practice, but rather a skill with its origin in mental exercise and with its object consisting in mentally hitting the mark.

“Therefore, the archer is basically aiming for himself. Through this, perhaps, he will succeed in hitting the target—his essential self.”

—Herrigel

On a sheet of paper, right in the middle of the sheet, write your own name the way you usually sign your name. Next, regard your signature from the following point of view: you are looking at a

drawing

which is your original creation—shaped, it is true, by the cultural influences of your life, but aren’t the creations of every artist shaped by such influences?

drawing

which is your original creation—shaped, it is true, by the cultural influences of your life, but aren’t the creations of every artist shaped by such influences?

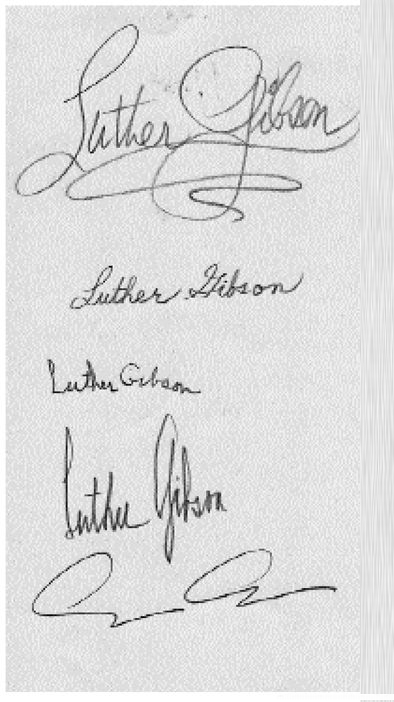

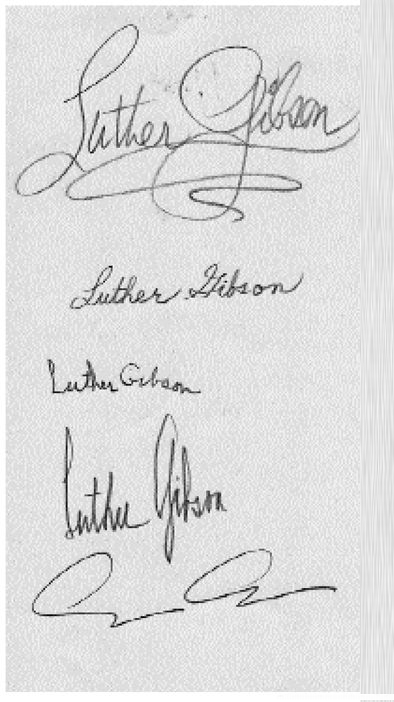

Every time you write your name, you have expressed yourself through the use of line. Your signature, “drawn” many times over, is expressive of you, just as Picasso’s line is expressive of him. The line can be “read” because, in writing your name, you have used the nonverbal language of art. Let’s try reading a line. There are signatures in the margin. All are the same name: Luther Gibson. Tell me, what is the first Luther Gibson like?

You would probably agree that Luther Gibson is more likely to be extroverted than introverted, more likely to wear bright colors than subtle ones, and, at least superficially, likely to be outgoing, talkative, even dramatic. Of course, these assumptions may or may not be correct, but the point is that this is how most people would read the nonverbal expression of the signature, because that’s what Luther Gibson is (nonverbally) saying.

Let’s look at the second Luther Gibson in the margin.

Now, look at the third signature. How would you describe him?

And another, the fourth signature.

And the last signature? How would you read that?

Now regard your own signature and respond to the nonverbal message of its line. Write your name in three different ways, each time responding to the message. Next, think back on how you responded differently to each of these signatures; recall that the name that was formed by the “drawings” did not change. What, then, were you responding to?

You were seeing and responding to the

felt,

individual qualities of each “drawn” line or set of lines. You responded to the felt speed of the line, the size and spacing of the marks, the muscle tension or lack of tension. All of that is precisely communicated by the line, the directional pattern or lack of pattern—in other words, by the whole signatures and all of their parts at once. A person’s signature is an individual expression so unique to the writer that it is identified legally as being “owned” by that single person and none other.

felt,

individual qualities of each “drawn” line or set of lines. You responded to the felt speed of the line, the size and spacing of the marks, the muscle tension or lack of tension. All of that is precisely communicated by the line, the directional pattern or lack of pattern—in other words, by the whole signatures and all of their parts at once. A person’s signature is an individual expression so unique to the writer that it is identified legally as being “owned” by that single person and none other.

Your signature, however, does more than identify you. It also expresses

you

and your individuality, your creativity. Your signature is

true

to yourself. In this sense, you already speak the nonverbal language of art: You are using the basic element of drawing, line, in an expressive way, unique to yourself.

you

and your individuality, your creativity. Your signature is

true

to yourself. In this sense, you already speak the nonverbal language of art: You are using the basic element of drawing, line, in an expressive way, unique to yourself.

In the chapters to follow, therefore, we won’t dwell on what you can do already. Instead, the aim is to teach you

how to see

so that you can use your expressive, individual line to draw your perceptions.

Drawing as a mirror and metaphor for the artisthow to see

so that you can use your expressive, individual line to draw your perceptions.

The object of drawing is not only to show what you are trying to portray, but also to show you. To illustrate how much personal style is embedded in drawings, I wish to show you two drawings on page 24, done at the same time by two different people—myself and artist/teacher Brian Bomeisler. We sat on either side of our model, Heather Allan. We were demonstrating how to draw a profile portrait for a group of students, the same profile portrait you will learn to do in Chapter Nine. The materials we used were identical, and we both drew for the same length of time—30 to 40 minutes. A viewer immediately sees that the model is the same—that is, both drawings achieve a likeness of Heather. But Brian’s portrayal expresses his response to Heather in his more “painterly” style (meaning emphasis on shapes), and my portrayal expresses

my

response in my more “linear” style (emphasis on line). By looking at my portrait of Heather, the viewer catches sight of me, and Brian’s drawing provides an insight into him. Thus, paradoxically, the more clearly you can perceive and draw what you see in the external world, the more clearly the viewer can see

you

, and the more you can know about yourself. Drawing becomes a metaphor for the artist.

my

response in my more “linear” style (emphasis on line). By looking at my portrait of Heather, the viewer catches sight of me, and Brian’s drawing provides an insight into him. Thus, paradoxically, the more clearly you can perceive and draw what you see in the external world, the more clearly the viewer can see

you

, and the more you can know about yourself. Drawing becomes a metaphor for the artist.

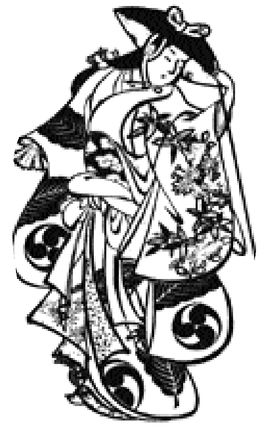

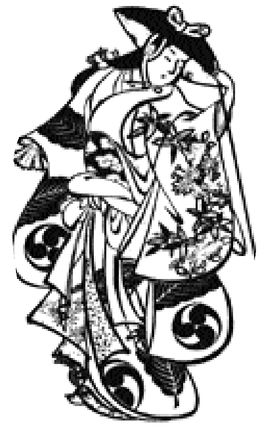

Torii Kiyotada (active 1723-1750),

Actor Dancing,

and Torii Kiyonobu I (1664-1729),

Woman Dancer

(c. 1708). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1949.

Actor Dancing,

and Torii Kiyonobu I (1664-1729),

Woman Dancer

(c. 1708). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1949.

Line expresses two different kinds of dances in the two Japanese prints. Try to visualize each dance. Can you hear the music in your imagination? Try to see how the character of the line controls your response to the drawing.

Other books

The Amazing Flight of Darius Frobisher by Bill Harley

The Man With Candy by Jack Olsen

Home Before Sundown by Barbara Hannay

The Etruscan Net by Michael Gilbert

Cold Winter Rain by Steven Gregory

Caught in the Billionaire's Embrace by Elizabeth Bevarly

Leviathan by Paul Auster

Her Vigilant Seal by Caitlyn O'Leary

Good Counsel by Eileen Wilks