The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (35 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

8.98Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Note that Degas’s Basic Unit was from the topmost edge of the hair to the neckband. The artist used the same Basic Unit in Figure 11-6, shown in the chapter on color.

The visible world is replete with foreshortened views of people, streets, trees, and flowers. Beginning students sometimes avoid these “difficult” views and search instead for “easy” views. With the skills you now have, this limiting of subject matter for your drawing is unnecessary. Edges, negative spaces, and sightings of relationships work together to make drawing foreshortened forms not just possible—they become downright enjoyable. As in learning any skill, learning the “hard parts” is challenging and exhilarating.

Looking aheadThe technique I have just taught you, “informal perspective,” relies only on sights taken on the plane. Most artists use informal perspective, even though they may have complete knowledge of formal perspective. One of the advantages of learning informal sighting is that it can be used for any subject matter, as you will see in the next exercise. You will be drawing a profile portrait, putting to use your skills of perceiving edges, spaces, and proportional relationships in drawing the human head.

Remember that realistic drawings of perceived subjects always require the same basic perceptual skills—the skills you are learning right now. Of course, this is true of other R-mode global skills. For example, once you have learned to drive, you can very likely drive any make of automobile.

In your next drawing, you will enjoy drawing the human head, a most intriguing and challenging subject.

Randa Caldwell.

Instructor Dana Crowe.

9

Facing Forward: Portrait Drawing with Ease

HUMAN FACES HAVE ALWAYS FASCINATED ARTISTS. To catch a likeness, to show the exterior in such a way that the inner person can be seen, is a challenging, inviting prospect. Moreover, a portrait can reveal not only the appearance and personality (the gestalt) of the sitter but also the soul of the artist. Paradoxically, the more clearly the artist sees the sitter, the more clearly the viewer can see through the likeness to perceive the artist. These revelations beyond the likeness are not intentional. They are simply the result of close, sustained R-mode observation.

Therefore, because we are searching for you through the images you draw, you will be drawing human faces in the next set of exercises. The more clearly you see, the better you will draw, and the more you will express yourself to yourself and to others.

Since portrait drawing requires very fine perceptions in order to produce a likeness, faces are effective for training beginners in seeing and drawing. The feedback on the correctness of perception is immediate and certain, because we all know when a drawing of a human head is correct in its general proportions. And if we know the sitter, we can make even more precise judgments about the accuracy of the perceptions.

But perhaps more important for our purposes, drawing the human head has a special advantage for us in our quest for ways to gain conscious access to our right-hemisphere functions. The right hemisphere of the human brain is specialized for the recognition of faces. People with right-hemisphere injury caused by a stroke or accident often have difficulty recognizing their friends or even recognizing their own faces in the mirror. Left-hemisphere-injured patients usually do not experience this deficit.

Beginners often think that drawing people is the hardest of all kinds of drawing. It isn’t, actually. As with any other subject matter, the visual information is right there, ready and available. Again, the problem is seeing. To restate a major premise of this book, drawing is always the same task—that is, every drawing requires the basic perceptual skills you are learning. Aside from complexity, one subject is not harder or easier than another. However, certain subjects often seem harder than others, probably because embedded symbol systems, which interfere with clear perceptions, are stronger for some subjects than for others.

Most people have a very strong, persistent symbol system for drawing the human head. For example, a common symbol for an eye is made of two curved lines enclosing a small circle (the iris). Your own unique set of symbols, as we discussed in Chapter Five, was developed and memorized during childhood and is remarkably stable and resistant to change. These symbols actually seem to override seeing, and therefore few people can draw a realistic human head. Even fewer can draw recognizable portraits.

Summing up, then, portrait drawing is useful to our goals for these reasons: First, it is a suitable subject for accessing the right hemisphere, which is specialized for recognition of human faces and for making the fine visual discriminations necessary to achieve a likeness. Second, drawing faces will help you to strengthen your ability to perceive proportional relationships, since proportion is integral to portraiture. Third, drawing faces is excellent practice in bypassing embedded symbol systems. And fourth, the ability to draw portraits with credible likenesses is a convincing demonstration to your ever-critical left hemisphere that you have—dare we say it?—talent for drawing. And you’ll find that drawing portraits is not difficult once you can shift to the artist’s way of seeing.

In drawing your profile portrait, you will be using all of the skills you have learned so far:

• How to perceive and draw edges

• How to perceive and draw spaces

• How to perceive and draw relationships

• How to perceive and draw (a bit of) lights and shadows (I will present more in-depth instruction on lights and shadows in Chapter Ten.)

• And in addition, you will acquire a new skill, how to perceive and draw the gestalt of your model—the character and personality behind the drawn image—by focussing intently on the first four skills.

Our main strategy for accessing R-mode remains the same: to present the brain with a task that L-mode will turn down.

A reminder: The global skill of drawing has five component skills.

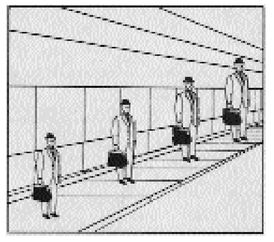

Fig. 9-1. The four figures are the same size.

Fig. 9-2. Mark the size of one figure on a piece of paper.

Fig. 9-3. Cut out a notch the size of one figure and measure each of the figures by fitting it into the cut-out notch.

The importance of proportion in portrait drawingAll drawing involves proportion, whether the subject is still life, landscape, figure drawing, or portrait drawing. Proportion is important whether an artwork’s style is realistic, abstract, or completely nonobjective (that is, without recognizable forms from the external world). Realistic drawing in particular depends heavily on proportional correctness. Therefore, realistic drawing is especially effective in training the eye to see the thing-as-it-is in its relational proportions. Individuals whose jobs require close estimations of size relationships—carpenters, dentists, dressmakers, carpet-layers, and surgeons—develop great facility in perceiving proportion. Creative thinkers in all fields benefit from enhanced awareness of part-to-whole relationships—from seeing both the trees and the forest.

Other books

Gambled - A Titan Novella by Harber, Cristin

Viriconium by Michael John Harrison

Private Scandal by Jenna Bayley-Burke

Lanyon, Josh - Adrien English 04 - Death of a Pirate King by Death of a Pirate King

Scandal in the Village by Shaw, Rebecca

Searching for Shona by Anderson, Margaret J.

Super Crunchers by Ian Ayres

Every Man Dies Alone by Hans Fallada

Blade Dance (A Cold Iron Novel Book 4) by D.L. McDermott

Alpha Kill - 03 by Tim Stevens