The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (37 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

2.12Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

3. Repeat the measurement in front of a mirror. Regard the reflection of your head. Without measuring, visually compare the bottom half with the top half of your head. Then use your pencil to repeat the measurement of eye level one more time.

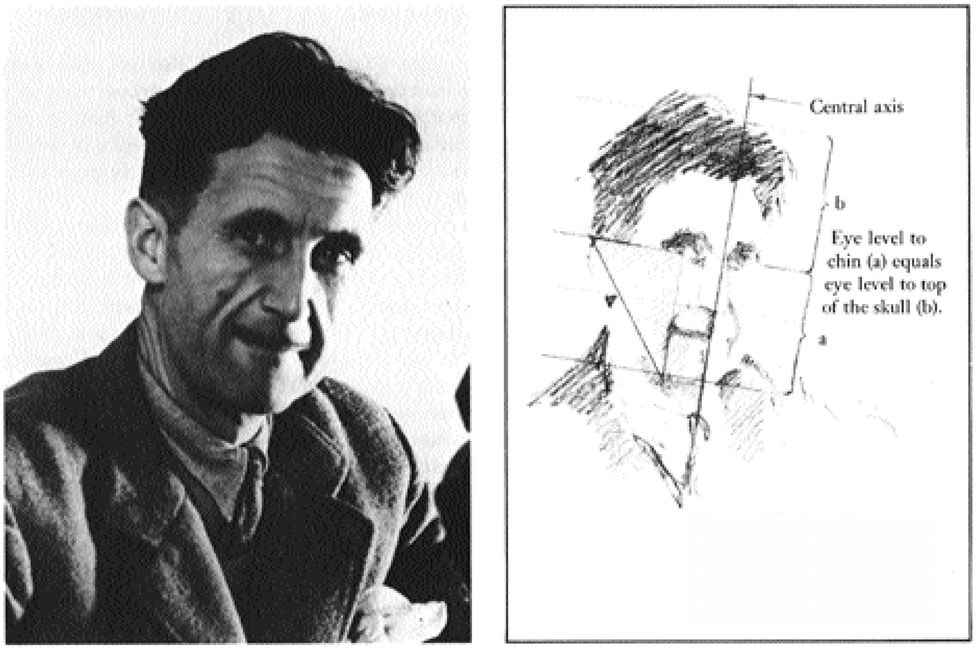

4. If you have newspapers or magazines handy, check this proportion in photographs of people, or use the photo of English writer George Orwell, Figure 9-11. Use your pencil to measure. You will find that:

Eye level to chin equals eye level to the top of the skull. This is an almost invariant proportion.

5. Check the photographs again. In each head, is the eye level at about the middle, dividing the whole shape of the head about in half? Can you clearly see that proportion? If not, turn on television to a news program and measure heads right on the television screen by placing your pencil flat on the screen, measuring first eye level to chin, then eye level to the top edge of the head. Now, take the pencil away and look again. Can you see the proportion clearly now?

Fig. 9-10.

Fig. 9-11. The late George Orwell, well-known writer who died in January 1950. Photo courtesy of BBC.

Fig. 9-12.

Many “police artists” are officers more or less assigned to putting together composite drawings of suspects from witnesses’ descriptions. The resulting drawings often display the perceptual error I’ve described in this section.

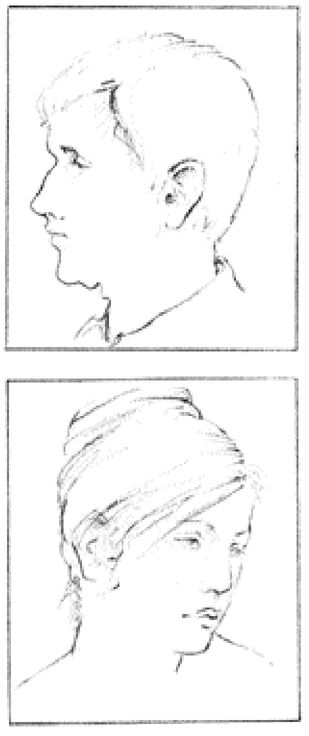

When you finally believe what you see, you will find that on nearly every head you observe, the eye level is at about the halfway mark. The eye level is almost never less than half—that is, almost never nearer to the top of the skull than to the bottom of the chin (See Figure 9-12). And if the hair is thick, the top half of the head—eye level to the topmost edge of the hair—is bigger than the bottom half.

The “chopped-off skull” creates the masklike effect so often seen in children’s drawings, abstract or expressionistic art, and in so-called “primitive” or “ethnic” art. This masklike effect of enlarging the features relative to the skull size, of course, can have tremendous expressive power, as seen, for example, in works by Picasso, Matisse, and Modigliani, and great works of other cultures. The point is that master artists, especially of our own time and culture, use the device by choice and not by mistake. Let me demonstrate the effect of misperception.

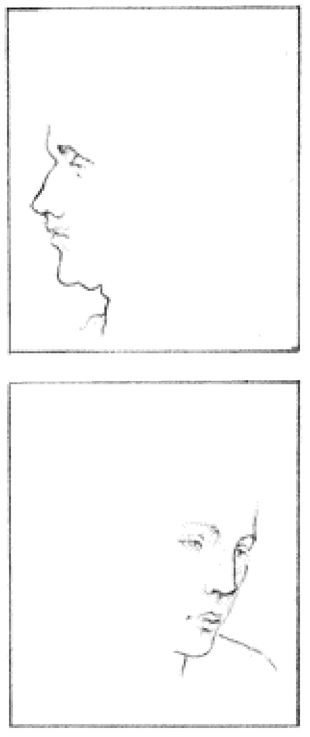

Irrefutable evidence that the top of the head is important after allFirst, I have drawn the lower part of the faces of two models, one in profile and one in three-quarter view (see Figure 9-13). Contrary to what one would expect, most students have few serious problems in learning to see and draw the features. The problem is not the features; it’s in perceiving the skull that things go wrong. What I want to demonstrate is how important it is to provide the full skull for the features—not to cut off the top of the head because your brain is less interested and makes you see it as smaller.

In Figure 9-13 are two sets of three drawings: First, the features only, without the rest of the skull; second, the identical features with the cut-off-skull error; and third, the identical features, this time with the full skull, which complements and supports the features.

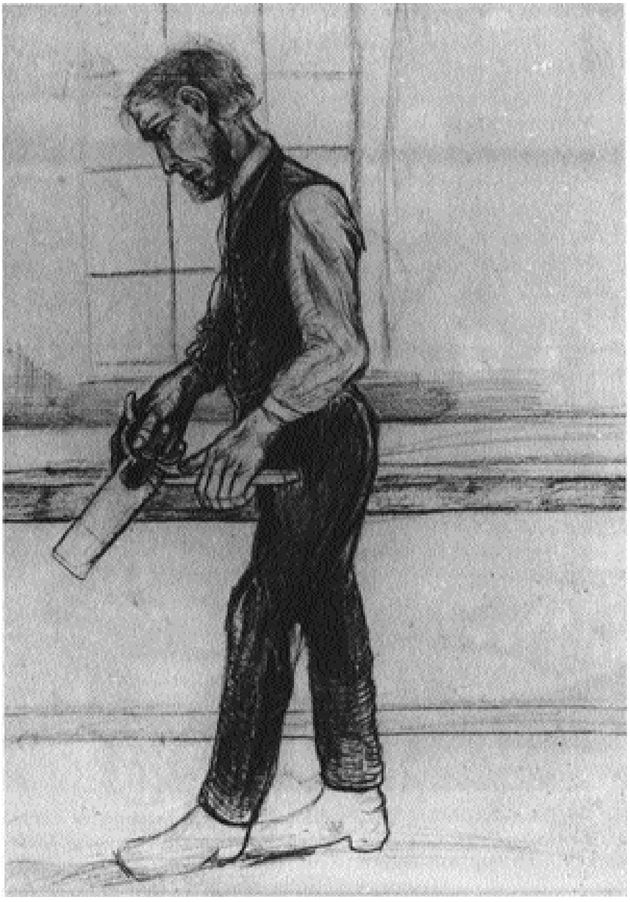

You can see that it’s not the features that cause the problem of wrong proportion; it’s the skull. Now turn to Figure 9-14 and see that Van Gogh in his 1880 drawing of the carpenter apparently made the “chopped-off skull” error in the carpenter’s head. Also, see the Dürer etching in Figure 9-16 in which the artist demonstrates the effort of diminishing the relative proportion of the skull to the features. Are you convinced? Is your logical left hemisphere convinced? Good. You will save yourself innumerable hours of baffling mistakes in drawing.

Fig. 9-13. The features only.

The cut-off-skull error, using the same features.

The same features again, this time with the full skull.

Fig. 9-14. Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890),

Carpenter

(1880). Courtesy of Rijksmuseum KröllerMüller, Otterlo.

Carpenter

(1880). Courtesy of Rijksmuseum KröllerMüller, Otterlo.

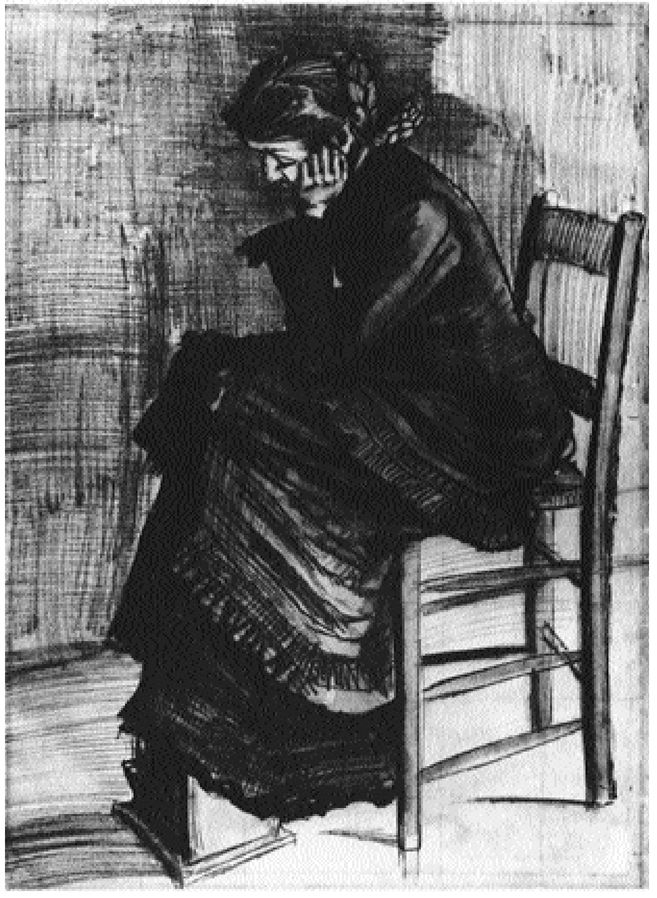

Van Gogh worked as an artist only during the last ten years of his life, from the age of 27 until he died at 37. During the first two years of that decade, Van Gogh did drawings only, teaching himself how to draw. As you can see in the drawing of the carpenter, he struggled with problems of proportion and placement of forms. By 1882, however—two years later—in his

Woman Mourning,

Van Gogh had overcome his difficulties with drawing and increased the expressive quality of his work.

Woman Mourning,

Van Gogh had overcome his difficulties with drawing and increased the expressive quality of his work.

Fig. 9-15. Vincent Van Gogh,

Woman Mourning

(1882). Courtesy of Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo.

Drawing another blank and getting a line on the profileWoman Mourning

(1882). Courtesy of Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo.

Draw another blank now, this time for a profile. The profile blank is a somewhat different shape—like an oddly shaped egg. This is because the human skull (Figure 9-17), seen from the side, is a different shape than the skull seen from the front. It’s easier to draw the blank if you look at the shapes of the negative spaces around the blank in Figure 9-17. Notice that the negative spaces are different in each corner.

Other books

El ladrón de días by Clive Barker

My Guardian (Bewitched and Bewildered Book 6) by Alanea Alder

A Great Deliverance by Elizabeth George

Wild in the Field by Jennifer Greene

The Pregnancy Shock by Lynne Graham

Why Is Milk White? by Alexa Coelho

Pyramid Quest by Robert M. Schoch

Maverick Wild (Harlequin Historical Series) by Stacey Kayne

The Second Forever by Colin Thompson

It's Not What You Think by Chris Evans