The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (31 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

11.07Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Fig. 8-4.

The next perception required is how wide the table is (from this viewpoint) in relation to its length. This apparent width relative to length will vary from viewpoint to viewpoint, depending on where the viewer’s eye level happens to be.

1.

Holding the pencil on a plane parallel to your eyes and at arm’s length, with the elbow locked to keep the scale constant, measure the width of the table. Place the eraser of the pencil so it coincides with one corner of the table and place your thumb at the other corner. This is your Basic Unit (Figure 8-5).

Holding the pencil on a plane parallel to your eyes and at arm’s length, with the elbow locked to keep the scale constant, measure the width of the table. Place the eraser of the pencil so it coincides with one corner of the table and place your thumb at the other corner. This is your Basic Unit (Figure 8-5).

2.

Still keeping your elbow locked and with the pencil still parallel to your eyes, carry that measurement to the long side of the table (Figure 8-5). How long is the table, relative to its width? In this instance, the ratio is one to one and a half (1:1½) (Figure 8-6).

Still keeping your elbow locked and with the pencil still parallel to your eyes, carry that measurement to the long side of the table (Figure 8-5). How long is the table, relative to its width? In this instance, the ratio is one to one and a half (1:1½) (Figure 8-6).

3.

Next, you will take a sight on the table legs by holding your pencil vertically, taking note of the angle of one leg relative to vertical. Are the table legs perfectly vertical or are they at an angle? Draw the leg closest to you. You can take a sight on the length of the leg relative (again) to the width, your Basic Unit (Figure 8-7).

Next, you will take a sight on the table legs by holding your pencil vertically, taking note of the angle of one leg relative to vertical. Are the table legs perfectly vertical or are they at an angle? Draw the leg closest to you. You can take a sight on the length of the leg relative (again) to the width, your Basic Unit (Figure 8-7).

Fig. 8-5.

Fig. 8-6.

Fig. 8-7.

“Point of view is worth eighty points of IQ.”

—Alan Kay, computer

scientist and Disney

Fellow

scientist and Disney

Fellow

Learning to draw in perspective requires that we see things as they are out there in the external world. We must put aside our prejudgments, our stored and memorized stereotypes and habits of thinking. We must overcome false interpretations, which are often based on what we think must be out there even though we may never have taken a really clear look at what is right in front of our eyes.

I’m sure you can see the connection to problem solving. One of the first steps in solving problems is to scan the relevant factors and to put things “into perspective” and “into proportion.” This process requires the capacity to see the various parts of a problem in their true relationship.

Defining perspectiveThe term “perspective” comes from the Latin word “prospectus,” meaning “to look forward.” Linear perspective, the system most familiar to us, was perfected during the Renaissance by European artists. Linear perspective enabled artists to reproduce visual changes of lines and forms as they appear in three-dimensional space.

Various cultures have developed different conventions or perspective systems. Egyptian and Oriental artists, for example, developed a kind of stair-step or tiered perspective, in which placement from bottom to top of the format indicated position in space. In this system, which is often used intuitively by children, the forms at the very top of the page—regardless of size—are considered to be the farthest away. More recently, artists have rebelled against rigid conventions of perspective and have invented new systems employing abstract spatial qualities of colors, textures, lines, and shapes.

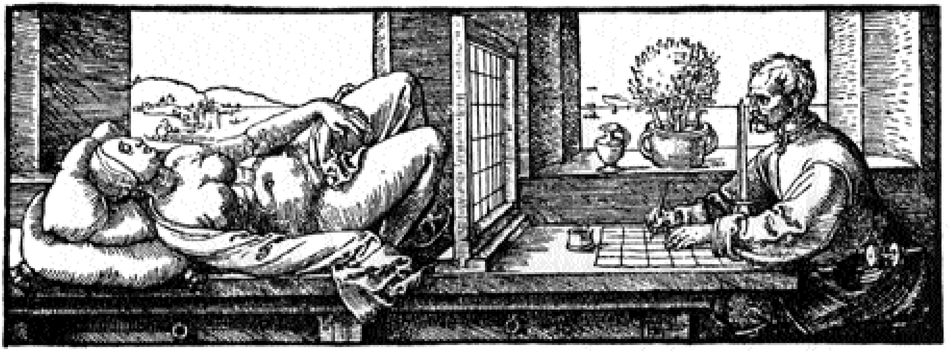

Fig. 8-8. Albrecht Dürer,

Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Woman

(1525). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Felix M. Warburg, 1918.

Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Woman

(1525). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Felix M. Warburg, 1918.

Traditional Renaissance perspective conforms most closely to the way people in our Western culture perceive objects in space. In our perceptions, parallel lines appear to converge at vanishing points on a horizon line (the viewer’s eye level) and forms appear to become smaller as distance from the viewer increases. For this reason, realistic drawing depends heavily on these principles. The Dürer etching (Figure 8-8) illustrates this perceptual system.

Dürer’s deviceThe great sixteenth-century Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer, invented a device to help him draw in proportion and in perspective. Your plastic Picture Plane is a simplified version of Dürer’s device. Let’s look at the artist’s depiction of his device in Figure 8-8. Dürer’s draughtsman, holding his head in a stationary position (note the vertical marker for his viewpoint), looks through an upright wire grid. The artist peers at his model from a viewpoint that foreshortens his visual image of the model—that is, a viewpoint in which the main axis of the woman’s figure from head to foot coincides with the artist’s line of sight. This view causes the more distant parts of the figure (the head and shoulders) to appear to be smaller than they actually are, and the nearby parts (the knees and lower legs) to appear to be larger.

Fig. 8-9. What Dürer saw: Sighting parts one by one.

A foreshortened view of a leg and foot, as seen flattened on the Picture Plane.

In front of Dürer’s draughtsman on his drawing table is a paper the same size as the wire grid, marked off with an identical grid of lines. The artist draws on the paper what he perceives through the grid, matching in his drawing the exact angles and curves and lengths of lines compared to the verticals and horizontals of the grid. In effect, he is copying what he sees flattened on the picture plane. If he copies just what he sees, he will produce on the paper a foreshortened view of the model. The proportions, shapes, and sizes will be contrary to what the artist knows about the actual proportions, shapes, and sizes of the human body; but only if he draws the untrue proportions he perceives will the drawing look true to life.

What did Dürer see through his grid? (See Figure 8-9.) Dürer sights point one, the top of the left knee, and marks that point on his gridded paper. Next, he sights point two, the top of the left hand, and then point three, the top of the left knee. Beyond these points he sights the torso and the head. He connects all the points and ends with a foreshortened drawing of the entire figure.

The problem with foreshortening in drawing is that what we know about the subject of a drawing somehow intrudes into the drawing, and we draw what we know rather than what we see. The purpose of Dürer’s device, using the grid and the fixed viewpoint, was to force himself to draw the form exactly as he saw it, with all of its “wrong” proportions. Then, paradoxically, the drawing “looked right.” A viewer of the drawing, then, might wonder how the draughtsman was able to make the drawing look “so real.”

The achievement, therefore, of Renaissance perspective was to codify and systematize a method of bypassing artists’ knowledge about shapes and forms. The science of “formal” perspective provided a means by which they could draw forms just as they appeared to the eye—including distortions created optically by a form’s position in space relative to the viewer’s eye.

The system worked beautifully and solved the problem of how to create an illusion of deep space on a flat surface, of re-creating the visible world. Dürer’s simple device evolved into a complicated mathematical system, enabling artists from the Renaissance onward to overcome their mental resistance to optical distortions of the true shapes of things and to draw realistically.

Formal perspective versus “informal” perspectiveBut the system of formal perspective is not without problems. Followed to the letter, strictly applied perspective rules can result in rather dry and rigid drawings. Perhaps the most serious problem with the formal perspective system is that it is so “left-brained.” It employs the style of left-hemisphere processing: analysis, sequential logical cogitation, and mental calculations within a pre-prescribed system. There are vanishing points, horizon lines, perspective of circles and ellipses, and so on. The system is detailed and cumbersome, the antithesis of R-mode style with its antic/serious, pleasurable quality. For example, in anything but the simplest one-point perspective setup (Figure 8-10), vanishing points may be several feet beyond the edge of the drawing paper, requiring pins and strings to mark them.

Fortunately, once you understand “informal” perspective (sighting), you don’t really need to know formal perspective at all. That’s not to say the study of perspective is not useful and interesting. In my view, knowledge never hurts! But sighting is sufficient for basic drawing skills.

Other books

Claire Delacroix by My Ladys Desire

The Ruins of Karzelek (The Mandrake Company series Book 4) by Lionsdrake, Ruby

Last Blood by Kristen Painter

A Shade Of Vampire 5: A Blaze Of Sun by Forrest, Bella

Sin by Josephine Hart

Protecting the Future (SEAL of Protection Book 8) by Susan Stoker

Protector of the Realm by Gun Brooke

The Oasis by Pauline Gedge

Blood of Wolves by Loren Coleman

Blood Oath by Tunstall, Kit