The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (29 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

9.77Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

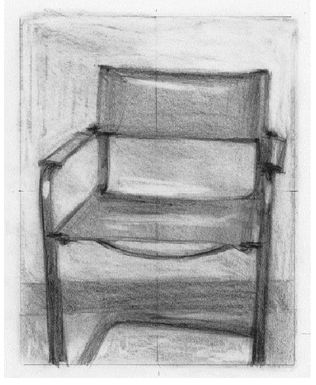

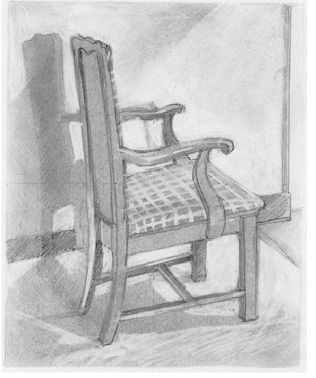

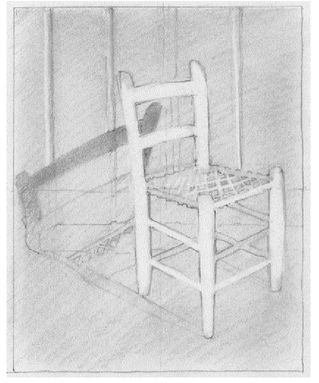

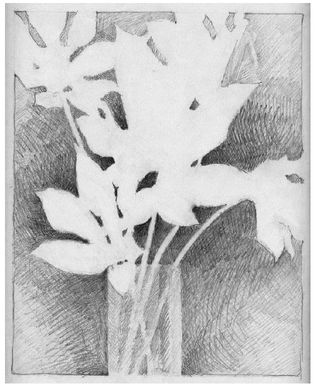

7. When you have finished drawing the edges of the spaces, you may want to “work up” the drawing a bit by using your eraser to remove the tone in some areas, perhaps erasing the negative spaces and leaving the chair in tone (Figure 7-15). If you see shadows on the floor or on the wall behind, you may want to add them to your drawing, perhaps adding in some tone with your pencil, or erasing out the negative spaces of the shadows. You may also want to “work up” the positive form of the chair itself, adding some of the interior contours.

After you have finished:I feel confident that your drawing will please you. One of the most striking characteristics of negative-space drawings is that no matter how mundane the subject—a chair, an eggbeater, a can opener—the drawing will seem beautiful.

Perhaps negative-space drawings remind us of our longing for unity, or perhaps of our actual unity with the world around us. No matter what the explanation, we simply like to look at negative-space drawings. Don’t you agree?

With only this brief lesson, you will begin to see negative spaces everywhere. My students often regard this as a great and joyful discovery. Practice seeing negative spaces as you go through your everyday routine and imagine yourself drawing those beautiful spaces. This mental practice at odd moments is extremely helpful in putting perceptual skills “on automatic,” ready to be integrated into a learned skill that you own.

What follows is one last example of the usefulness of negative spaces.

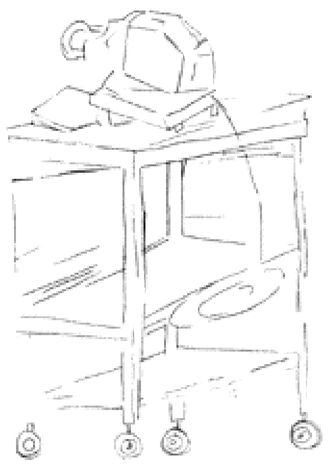

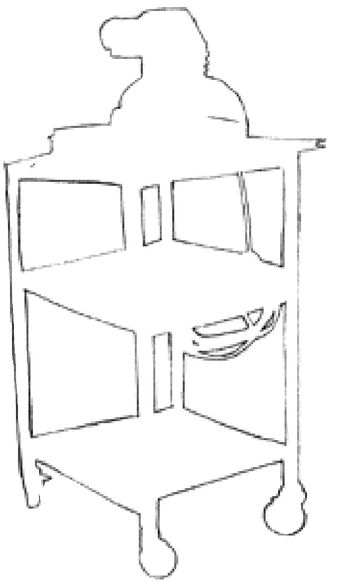

The cognitive battle of perceptionFigures 7-16 and 7-17 show an interesting graphic record of the struggle and its resolution in two drawings by a student of a cart and slide projector. In Figure 7-16, the first drawing, the student had great difficulty reconciling his stored knowledge of what the objects were “supposed to look like” with what he saw. Notice in the drawing that the legs of the cart are all the same length, and a symbol is used for the wheels. When he shifted to using a viewfinder and drawing only the shapes of the negative spaces, he was far more successful (Figure 7-17). The visual information apparently came through clearly; the drawing looks confident and as though it were done with ease. And, in fact, it was done with ease, because using negative space enables one to escape the mental crunch that occurs when perceptions don’t match conceptions.

It’s not that the visual information gathered by regarding spaces rather than objects is really less complex or is in any way easier to draw. The spaces, after all, share edges with the form. But by looking at the spaces, we free R-mode from the domination of L-mode. Put another way, by focusing on information that does not suit the style of the verbal system, we cause the job to be shifted to the mode appropriate for drawing. Thus, the conflict ends, and in R-mode, the brain processes spatial, relational information with ease.

Showing all manner of negative spacesThese drawings are intriguingly pleasurable to look at, even when the positive forms are as mundane as schoolroom chairs. One could speculate that the reason is that the method of drawing raises to a conscious level the unity of positive and negative shapes and spaces. Another reason may be that the technique results in excellent compositions with particularly interesting divisions of shapes and spaces within the format.

Learning to see clearly through drawing can surely enhance your capacity to take a clear look at problems and to be better able to see things in perspective. In the next chapter, we’ll take up the perception of relationships, a skill you can put to use in as many directions as your mind can take you.

Fig. 7-16.

Fig. 7-17.

Demonstration drawing by instructor Lisbeth Firmin.

Demonstration drawing by the author.

Demonstration drawing by the author.

Student drawing.

Student drawing by Sandy DePhillippo.

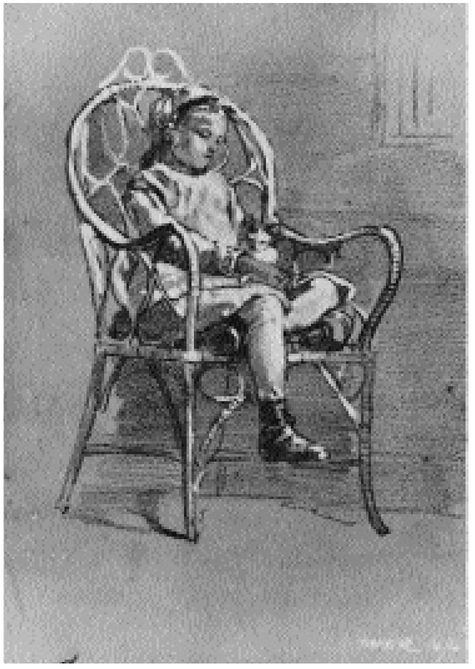

Winslow Homer (1836-1910),

Child Seated in a Wicker Chair

(1874). Courtesy of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Child Seated in a Wicker Chair

(1874). Courtesy of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Observe how Winslow Homer used negative space in his drawing of a child in a chair. Try copying this drawing.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Studies of Arms and Legs.

Courtesy of Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Studies of Arms and Legs.

Courtesy of Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Copy this drawing. Turn the original upside down and draw the negative spaces. Then turn the drawing right side up and complete the details inside the forms. These “difficult”

foreshortened

forms become easy to draw if attention is focused on the spaces around the forms.

foreshortened

forms become easy to draw if attention is focused on the spaces around the forms.

8

Relationships in a New Mode: Putting Sighting in Perspective

Other books

That Summer in Sicily by Marlena de Blasi

Savage Courage by Cassie Edwards

Crazy Ever After by Kelly Jamieson

The Sinner by Tess Gerritsen

Ice in My Veins by Kelli Sullivan

Moloch: Or, This Gentile World by Henry Miller

The Unbound by Victoria Schwab

William H. Hallahan - by The Monk