The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (15 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

2.02Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Fig. 4-12; far right: The Picasso drawing copied upside down the next day by the same student.

This puzzle puts L-mode into a logical box: how to account for this sudden ability to draw well, when the verbal mode has been eased out of the task. The left brain, which admires a job well done, must now consider the possibility that the disdained right brain is good at drawing

For reasons that are still unclear, the verbal system immediately rejects the task of “reading” and naming upside-down images. L-mode seems to say, in effect, “I don’t do upside down. It’s too hard to name things seen this way, and, besides, the world isn’t upside down. Why should I bother with such stuff?”

Well, that’s just what we want! On the other hand, the visual system seems not to care. Right side up, upside down, it’s all interesting, perhaps even more interesting upside down because R-mode is free of interference from its verbal partner, which is often in a “rush to judgment” or, at least, a rush to recognize and name.

Why you did this exercise:The reason you did this exercise, therefore, is to experience escaping the clash of conflicting modes—the kind of conflict and even mental paralysis that the “Vase/Faces” exercise caused. When L-mode drops out voluntarily, conflict is avoided and R-mode quickly takes up the task that is appropriate for it: drawing a perceived image.

Getting to know the L→

R shift

Two important points of progress emerge from the upside-down exercise. The first is your conscious recall of how you felt after you made the L→R cognitive shift. The quality of the R-mode state of consciousness is different from the L-mode. One can detect those differences and begin to recognize when the cognitive shift has occurred. Oddly, the moment of shifting between states of consciousness always remains out of awareness. For example, one can be aware of being alert and then of being in a daydream, but the moment of shifting between the two states remains elusive. Similarly, the moment of the cognitive shift from L→R remains out of awareness, but once you have made the shift, the difference in the two states is accessible to knowing. This knowing will help to bring the shift under conscious control—a main goal of these lessons.

“Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness, as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation.”

—William James

The Varieties of Religious

Experience,

1902

The Varieties of Religious

Experience,

1902

L-mode is the “right-handed,” left-hemisphere mode. The L is foursquare, upright, sensible, direct, true, hard-edged, unfanciful, forceful.

R-mode is the “left-handed,” right-hemisphere mode. The R is curvy, flexible, more playful in its unexpected twists and turns, more complex, diagonal, fanciful.

“I have supposed a Human Being to be capable of various physical states, and varying degrees of consciousness, as follows:

“(a) the ordinary state, with no consciousness of the presence of Fairies;

“(b) the ‘eerie’ state, in which, while conscious of actual surroundings, he is

also

conscious of the presence of Fairies;

also

conscious of the presence of Fairies;

“(c) a form of trance, in which, while

un

conscious of actual surrounding, and apparently asleep, he (i.e., his immaterial essence) migrates to other scenes, in the actual world, or in Fairyland, and is conscious of the presence of Fairies.”

un

conscious of actual surrounding, and apparently asleep, he (i.e., his immaterial essence) migrates to other scenes, in the actual world, or in Fairyland, and is conscious of the presence of Fairies.”

—Lewis Carroll

Preface to

Sylvie and

Bruno

Preface to

Sylvie and

Bruno

The second insight gained from the exercise is your awareness that shifting to the R-mode enables you to see in the way a trained artist sees, and therefore to draw what you perceive.

Now, it’s obvious that we can’t always be turning things upside down. Your models are not going to stand on their heads for you, nor is the landscape going to turn itself upside down or inside out. Our goal, then, is to teach you how to make the cognitive shift when perceiving things in their normal right-side-up positions. You will learn the artist’s “gambit”: to direct your attention toward visual information that L-mode cannot or will not process. In other words, you will always try to present your brain with a task the language system will refuse, thus allowing R-mode to use its capability for drawing. Exercises in the coming chapters will show you some ways to do this.

A review of R-modeIt might be helpful to review what R-mode feels like. Think back. You have made the shift several times now—slightly, perhaps, while doing the Vase/Faces drawings and more intensely just now while drawing the “Stravinsky.”

In the R-mode state, did you notice that you were somewhat unaware of the passage of time—that the time you spent drawing may have been long or short, but you couldn’t have known until you checked it afterward? If there were people near, did you notice that you couldn’t listen to what they said—in fact, that you didn’t want to hear? You may have heard sounds, but you probably didn’t care about figuring out the meaning of what was being said. And were you aware of feeling alert, but relaxed—confident, interested, absorbed in the drawing and clear in your mind?

Most of my students have characterized the R-mode state of consciousness in these terms, and the terms coincide with my own experience and accounts related to me of artists’ experiences. One artist told me, “When I’m really working well, it’s like nothing else I’ve ever experienced. I feel at one with the work: the painter, the painting, it’s all one. I feel excited, but calm—exhilarated, but in full control. It’s not exactly happiness; it’s more like bliss. I think it’s what keeps me coming back and back to painting and drawing.”

R-mode state is indeed pleasurable, and in that mode you can draw well. But there is an additional advantage: Shifting to R-mode releases you for a time from the verbal, symbolic domination of L-mode, and that’s a welcome relief. The pleasure may come from resting the left hemisphere, stopping its chatter, keeping it quiet for a change. This yearning to quiet L-mode may partially explain centuries-old practices such as meditation and self-induced altered states of consciousness achieved through fasting, drugs, chanting, and alcohol. Drawing induces a focused, alert state of consciousness that can last for hours, bringing significant satisfaction.

Before you read further, do at least one or two more drawings upside down. Use either the reproduction in Figure 4-13, or find other line drawings to copy. Each time you draw, try consciously to experience the R-mode shift, so that you become familiar with how it feels to be in that mode.

Recalling the art of your childhoodIn the next chapter we’ll review your childhood development as an artist. The developmental sequence of children’s art is linked to development changes in the brain. In the early stages, infants’ brain hemispheres are not clearly specialized for separate functions. Lateralization—the consolidation of specific functions into one hemisphere or the other—progresses gradually through the childhood years, paralleling the acquisition of language skills and the symbols of childhood art.

Lateralization is usually complete by around age ten, and this coincides with the period of conflict in children’s art, when the symbol system seems to override perceptions and to interfere with accurate drawing of those perceptions. One could speculate that conflict arises because children may be using the “wrong” brain mode—L-mode—to accomplish a task best suited for R-mode. Perhaps they simply cannot work out a way to shift to the visual mode. Also, by age ten, language dominates, adding further complication as names and symbols overpower spatial, holistic perceptions.

“I know perfectly well that only in happy instants am I lucky enough to lose myself in my work. The painter-poet feels that his true immutable essence comes from that invisible realm that offers him an image of eternal reality. . . .

I feel that I do not exist in time, but that time exists in me. I can also realize that it is not given to me to solve the mystery of art in an absolute fashion. Nonetheless, I am almost brought to believe that I am about to get my hands on the divine.”

—Carlo Carra

“The Quadrant of the

Spirit,” 1919

“The Quadrant of the

Spirit,” 1919

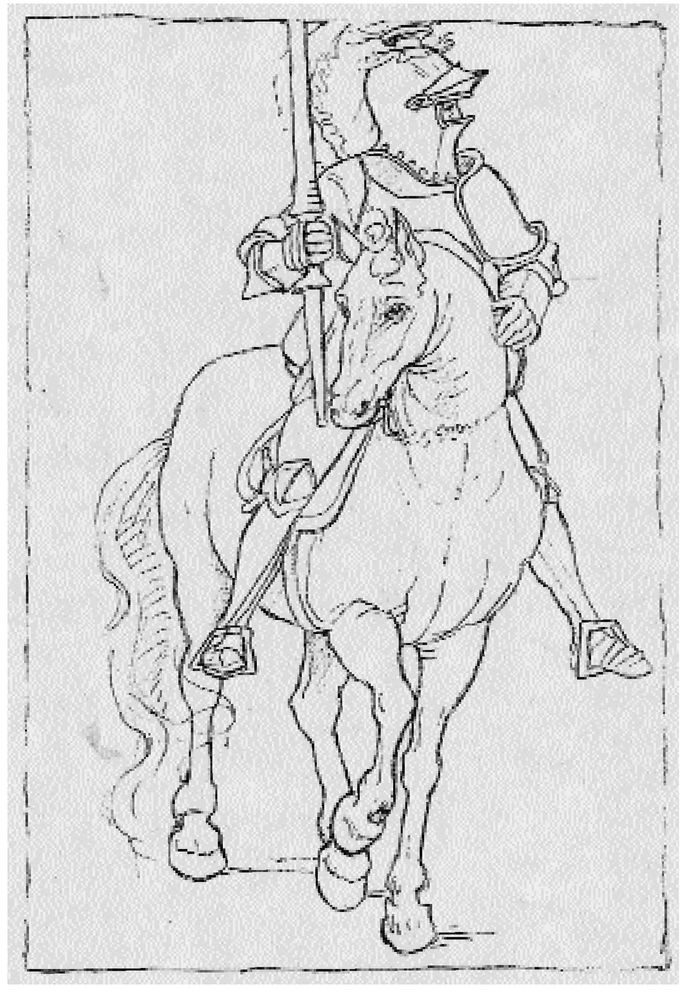

This sixteenth-century drawing by an unknown German artist offers a wonderful opportunity to practice upside-down drawing.

Fig. 4-13. Line drawing copy of the German horse and rider.

Reviewing your childhood art is important for several reasons: to look back as an adult at how your set of drawing symbols developed from infancy onward; to reexperience the increasing complexity of your drawing as you approached adolescence; to recall the discrepancy between your perceptions and your drawing skills; to view your childhood drawings with a less critical eye than you were able to manage at the time; and finally, to set your childhood symbol system aside and move on to an adult level of visual expression by using the appropriate brain mode—the right mode—for the task of drawing.

5

Drawing on Memories: Your History as an Artist

Other books

Revealed by Amanda Valentino

Second Opinion by Suzanne, Lisa

What's The Worst That Could Happen by Donald Westlake

The Devil's Deuce (The Barrier War) by Moses, Brian J.

Future Winds by Kevin Laymon

Tricking Loki by Shara Azod, Marteeka Karland

The Strangler's Honeymoon by Hakan Nesser

News For Dogs by Lois Duncan

The Once and Future King by T. H. White

Significant Others by Baron, Marilyn