The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (21 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

5.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Pure Contour Drawing is so effective at producing this strong shift that many artists routinely begin drawing with at least a short session of the method, in order to start the process of shifting to R-mode.

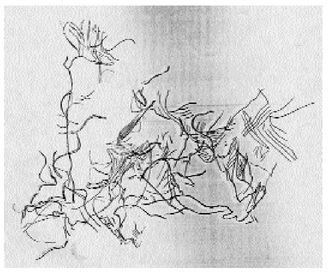

Looking at your drawing, a tangled mass of pencil marks, perhaps you will say, “What a mess!” But look more closely and you will see that these marks are strangely beautiful. Of course, they do not represent the hand, only its details, and details within details. You have drawn complex edges from actual perceptions. These are not quick, abstract, symbolic representations of the wrinkles in your palm. They are painstakingly accurate, excruciatingly intricate, entangled, descriptive, and specific marks—just what we want at this point. I believe that these drawings are visual records of the R-mode state of consciousness. As a witty friend of mine, writer Judi Marks, remarked on viewing a Pure Contour Drawing for the first time, “No one in their left mind would do a drawing like that!”

Why you did this exerciseThe most important reason for this exercise is that Pure Contour Drawing apparently causes L-mode to “reject the task,” enabling you to shift to R-mode. Perhaps the lengthy, minute observation of severely limited, “non-useful,” and “boring” information—information that defies verbal description—is incompatible with L-mode’s thinking style.

Note that:

The paradox of the Pure Contour Drawing exercise• Your verbal mode may object and object, but eventually will “bow out,” leaving you “free” to draw. This is why I asked you to continue drawing until the timer sounds.

• The marks you make in R-mode are different from and often more beautiful than marks made in your more usual L-mode state of consciousness.

• Anything can be a subject for a Pure Contour drawing: a feather, a piece of shredded bark, a lock of hair. Once you have shifted to R-mode, the most ordinary things become inordinately beautiful and interesting. Can you remember the sense of wonder you had as a child, poring over some tiny insect or a dandelion?

For reasons that are still unclear, Pure Contour Drawing is one of the key exercises in learning to draw. But it’s a paradox: Pure Contour Drawing, which doesn’t produce a “good” drawing (in students’ estimations), is the best exercise for effectively and efficiently causing students later to achieve good drawing. Even more important, though, this is the exercise that revives our childhood wonder and the sense of beauty found in ordinary things.

A possible explanationApparently, in our habitual use of brain modes, L-mode seeks quickly to recognize (and name and categorize) by picking out details, while R-mode wordlessly perceives whole configurations and seeks how the parts fit together—or perhaps whether the parts fit together.

In regarding a hand, for example, the nails, the wrinkles and creases are details and the hand itself is the whole configuration. This “division of labor” works fine in ordinary life. In drawing a hand, however, one must give equal attention—visual attention—to both the configuration and the details and how they fit together into the whole. Pure Contour Drawing may function as a sort of “shock treatment” for the brain, forcing it to do things differently.

Pure Contour Drawing, I believe, causes L-mode to “drop out,” perhaps, as I mentioned before, through simple boredom. (“I’ve already named it—it’s a wrinkle, I tell you. They’re all alike. Why bother with all this looking.”) Once L-mode has “dropped out,” it seems possible that R-mode then perceives each wrinkle—normally regarded as a detail—as a whole configuration, made up of even smaller details. Then each detail of each wrinkle becomes a further whole, made up of ever-smaller parts, and so on, going deeper and deeper into ever expanding complexity. There is some similarity, I believe, to the phenomenon of fractals, in which whole patterns are constructed of smaller detailed whole patterns, which are constructed of ever smaller, detailed whole patterns.

“In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is to surrender to them. When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualizing, you probably hunt about till you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning clear as one can through pictures or sensations.”

—George Orwell

“Politics and the English

Language,” 1968

“Politics and the English

Language,” 1968

If perhaps you did not attain a shift to R-mode in your first Pure Contour Drawing, please be patient with yourself. You may have a very determined verbal system. I suggest that you try again. You might try using a crumpled piece of paper, a flower, or any complex object that appeals to you. My students sometimes have to make two or even three tries in order to “win out” against their strong verbal modes.

Set a timer, perhaps for eight or even ten minutes. In the beginning, it takes time to cause a shift to R-mode. Later on, as American artist Robert Henri proposed in the sidebar quotation on page 5, the shift “to the higher state” will occur just by starting to draw.

These strange marks on the wall of a cave were made by Paleolithic humans. In their intensity, the marks seem to resemble Pure Contour Drawing.

—

Shamans of Prehistory,

J. Clottes and D. Lewis-

Williams. New York:

Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,

1996

Shamans of Prehistory,

J. Clottes and D. Lewis-

Williams. New York:

Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,

1996

Whatever the actual reason may be, I can assure you that Pure Contour Drawing will permanently change your ability to perceive. From this point onward, you will start to see in the way an artist sees and your skills in seeing and drawing will progress rapidly.

Look at the Pure Contour Drawing of your hand one more time and appreciate the quality of the marks you made in R-mode. Again, these are not the quick, glib, stereotypic marks of symbolic L-mode. These marks are true records of perception.

The next exercise will pull together everything learned so far and you will be doing a wonderful “real” drawing.

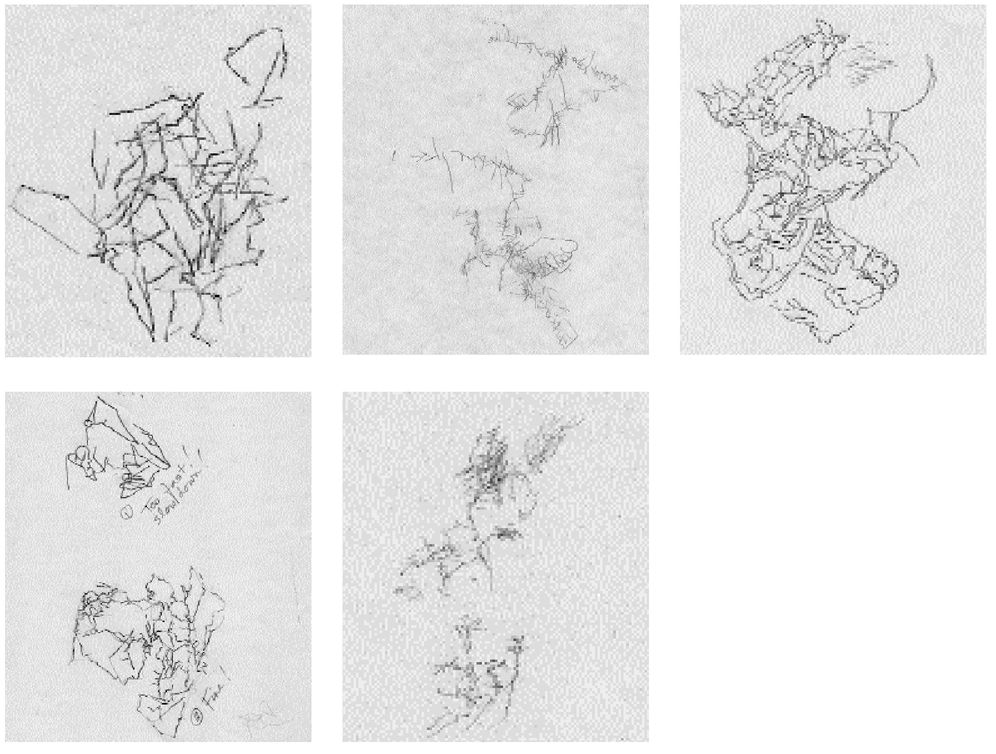

Student showing: A record of an alternative stateFollowing is a Student Showing of some Pure Contour Drawings. What strange and marvelous markings are these! Never mind that the drawings don’t resemble greatly the overall configuration of a hand—that’s to be expected. We will attend to the overall configuration in the next exercise, “Modified Contour Drawing.”

In Pure Contour Drawing, it is the quality of the marks and their character that we care about. The marks, these living hieroglyphs, are records of perceptions. To be found nowhere in the drawings are the thin, glib, stereotypic marks of casual, rapid L-mode symbolic processing. Instead, we see rich, deep, intuitive marks made in response to the thing-as-it-is, the thing as it exists out there, marks that delineate the is-ness of the object. Blind swimmers have seen! And seeing, they have drawn.

Before moving on to the next step, Modified Contour Drawing, let’s review the important concept of edges in art.

The first component skill: The perception of edgesPure Contour Drawing has introduced you to the first component skill of drawing: the perception of edges. In drawing, the term

edge

has a special meaning, different from its ordinary definition as a

border

or

outline.

edge

has a special meaning, different from its ordinary definition as a

border

or

outline.

In drawing, an edge is where two things come together. In the Pure Contour Drawing you just finished, for example, the edge you drew was the place (the wrinkle) where two parts of the flesh of your palm came together to form a single boundary for both parts. That shared boundary, in drawing, is described by a line that is called a contour line. In drawing, therefore, a line (a contour line or, more simply, a contour) is always the border of two things simultaneously—that is, a shared edge. The Vase/Faces exercise illustrates this concept. The line you drew was simultaneously the edge of the profile and the edge of the vase.

To sum up this concept: In drawing, an edge is always a shared boundary.

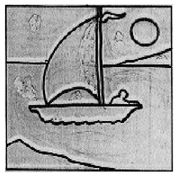

Fig. 6-2.

A good definition of “picture plane” from

The Art Pack,

Key Definitions/Key Styles, 1992.

The Art Pack,

Key Definitions/Key Styles, 1992.

“Picture plane: Often used—erroneously—to describe the physical surface of a painting, the picture plane is in fact a mental construct—like an imaginary plane of glass . . . Alberti (the Italian Renaissance artist) called it a ‘window’ separating the viewer from the picture itself . . . ”

John Elsum, in his 1704 book

The Art of Painting After the Italian Manner,

gave instructions for making “a handy device”:

The Art of Painting After the Italian Manner,

gave instructions for making “a handy device”:

“Take a Square Frame of Wood about one foot large, and on this make a little grate [grid] of Threads, so that crossing one another they may fall into perfect Squares about a Dozen at least, then place [it] between your Eye and the Object, and by this grate imitate upon your Table [drawing surface] the true Posture it keeps, and this will prevent you from running into Errors. The more Work is to be [fore]shortened the smaller are to be the Squares.”

Quoted in

A Miscellany of Artists’ Wisdom,

compiled by Diana Craig, Philadelphia: Running Press, 1993, p. 79.

A Miscellany of Artists’ Wisdom,

compiled by Diana Craig, Philadelphia: Running Press, 1993, p. 79.

The child’s jigsaw puzzle, Figure 6-2, illustrates this important point. The edge of the boat is shared with the water. The edge of the sail is shared with the sky and the water. Put another way, the water stop where the boat begins—a shared edge. The water and the sky stop where the sail begins—shared edges.

Note also that the outer edge of the puzzle—its frame or

format,

meaning the bounding edge of the composition—is also the outer edge of the sky-shape, the land-shapes, and the water-shape.

format,

meaning the bounding edge of the composition—is also the outer edge of the sky-shape, the land-shapes, and the water-shape.

Other books

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Gawande, Atul

Jennifer August by Knight of the Mist

London Urban Legends by Scott Wood

How To Set Up An FLR by Green, Georgia Ivey

Get a Clue by Jill Shalvis

Three Women of Liverpool by Helen Forrester

Slaves of the Billionaire by Raven, Winter

Witches Under Way by Geary, Debora

The Bronze Bow by Elizabeth George Speare

Black Sea Affair by Don Brown