The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (42 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

9.53Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“Portrait of Joy” by student Jerome Broekhuijsen.

A student drawing by Heather Tappen.

Demonstration drawing by the author.

“Portrait of Scott” demonstration drawing by instructor Beth Furmin.

10

The Value of Logical Lights and Shadows

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895).

Self-Portrait,

c. 1885. Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Self-Portrait,

c. 1885. Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Fig. 10-1. Drawing by student Elizabeth Arnold.

Light logic.

Light falls on objects and (logically) results in the four aspects of light/shadow:

Light falls on objects and (logically) results in the four aspects of light/shadow:

1.

Highlight:

The brightest light, where light from the source falls most directly on the object.

Highlight:

The brightest light, where light from the source falls most directly on the object.

2.

Cast shadow:

The darkest shadow, caused by the object’s blocking of light from the source.

Cast shadow:

The darkest shadow, caused by the object’s blocking of light from the source.

3.

Reflected light:

A dim light, bounced back onto the object by light falling on surfaces around the object.

Reflected light:

A dim light, bounced back onto the object by light falling on surfaces around the object.

4.

Crest shadow:

A shadow that lies on the crest of a rounded form, between the highlight and the reflected light. Crest shadows and reflected lights are difficult to see at first, but are the key to “rounding up” forms for the illusion of 3-D on the flat paper.

Crest shadow:

A shadow that lies on the crest of a rounded form, between the highlight and the reflected light. Crest shadows and reflected lights are difficult to see at first, but are the key to “rounding up” forms for the illusion of 3-D on the flat paper.

Now that you have gained experience with the first three perceptual skills of drawing—the perception of edges, spaces, and relationships—you are ready to put them together with the fourth skill, the perception of lights and shadows. After the mental stretch and effort of sighting relationships, you will find that drawing lights and shadows is especially joyful. This is the skill most desired by drawing students. It enables them to make things look three-dimensional through the use of a technique students often call “shading,” but which in art terminology is called “light logic.”

This term means just what it says: Light falling on forms creates lights and shadows in a logical way. Look for a moment at Henry Fuseli’s self-portrait (Figure 10-2). Clearly, there is a source of light, perhaps from a lamp. This light strikes the side of the head nearest the light source (the side on your left, as Fuseli faces you). Shadows are logically formed where the light is blocked, for example, by the nose. We constantly use this R-mode visual information in our everyday perceptions because it enables us to know the three-dimensional shapes of objects we see around us. But, like much R-mode processing, seeing lights and shadows remains below the conscious level; we use the perceptions without “knowing” what we see.

Learning to draw requires learning consciously to see lights and shadows and to draw them with all their inherent logic. This is new learning for most students, just as learning to see complex edges, negative spaces, and the relationships of angles and proportions are newly acquired skills.

Seeing valuesLight logic also requires that you learn to see differences in tones of light and dark. These tonal differences are called “values.” Pale, light tones are called “high” in value, dark tones “low” in value. A complete value scale goes from pure white to pure black with literally thousands of minute gradations between the two extremes of the scale. An abbreviated scale with twelve tones in evenly graduated steps between light and dark is shown in Figure 11-4 in the color section following page 210.

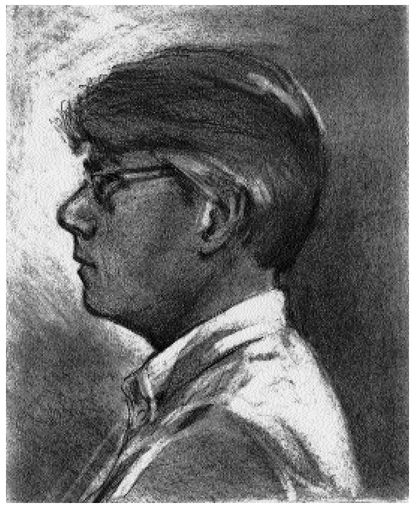

Fig. 10-2. Henry Fuseli (1741-1825),

Portrait of the Artist.

Courtesy of The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Portrait of the Artist.

Courtesy of The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Find the four aspects of light logic in Fuseli’s self-portrait.

1.

Highlights:

Forehead, cheeks, etc.

Highlights:

Forehead, cheeks, etc.

2.

Cast shadows:

Cast by the nose, lips, hands.

Cast shadows:

Cast by the nose, lips, hands.

3.

Reflected lights:

Side of the nose, side of the cheek.

Reflected lights:

Side of the nose, side of the cheek.

4.

Crest shadows:

Crest of the nose, crest of the cheek, temple.

Crest shadows:

Crest of the nose, crest of the cheek, temple.

In pencil drawing, the lightest possible light is the white of the paper. (See the white areas on Fuseli’s forehead, cheeks, and nose.) The darkest dark appears where the pencil lines are packed together in a tone as dark as the graphite will allow. (See the dark shadows cast by Fuseli’s nose and hand.) Fuseli achieved the many tones between the lightest light and the darkest dark by various methods of using the pencil: solid shading, crosshatching, and combinations of techniques. Many of the white shapes he actually erased out, using an eraser as a drawing tool. (See the highlights on Fuseli’s forehead.)

“Shadows are capricious. They change constantly—with time of day, wattage of light bulbs, placement of lamps, and changes in your own location. Although you depend on shadow for visual information about the form of an object, you are not usually aware of it as a quality separate from the object itself. You usually discount the shadow and exclude it from conscious perception of the object. After all, shadows change, but objects do not.”

—Carolyn M. Bloomer

Principles of Visual

Perception,

New York:

Van Nostrand Reinhold,

1976

Principles of Visual

Perception,

New York:

Van Nostrand Reinhold,

1976

In this chapter, I’ll show you how to see and draw lights and shadows as shapes and how to perceive value relationships to achieve “depth” or three-dimensionality in your drawings. These skills lead directly to color and subsequently to painting, as I outlined in the Preface.

As we proceed, keep in mind the following: The perception of edges (line) leads to the perception of shapes (negative spaces and positive shapes), drawn in correct proportion and perspective (sighting). These skills lead to the perception of values (light logic), which leads to the perception of colors as values, which leads to painting.

The role of R-mode in perceiving shadowsIn the same curious way that L-mode apparently will pay almost no attention to negative space or upside-down information, it seems also to ignore lights and shadows. L-mode, after all, may be unaware that R-mode perceptions help with naming and categorizing.

You will therefore need to learn to see lights and shadows at a conscious level. To illustrate for yourself how we interpret rather than see lights and shadows, turn this book upside down and look at Gustave Courbet’s

Self-portrait,

Figure 10-3. Upside down, the drawing looks entirely different—simply a pattern of dark areas and light areas.

Self-portrait,

Figure 10-3. Upside down, the drawing looks entirely different—simply a pattern of dark areas and light areas.

Now, turn the book right side up. You will see that the dark/ light pattern seems to change and, in a sense, disappear into the three-dimensional shape of the head. This is another of the many paradoxes of drawing: If you draw the shapes of lighted areas and shadowed areas just as you perceive them, a viewer of your drawing will not notice those shapes. Instead, the viewer will wonder how you were able to make your subject so “real,” meaning three-dimensional.

Fig. 10-3.

Self-portrait,

Gustave Courbet, 1897. Courtesy of The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Self-portrait,

Gustave Courbet, 1897. Courtesy of The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Other books

Hurricane Gold by Charlie Higson

3013: FATED by Susan Hayes

The Watchers by Reakes, Wendy

Held by You by Cheyenne McCray

Everything We Ever Wanted by Sarah S.

Gifts of Desire by Kella McKinnon

Roo'd by Joshua Klein

Undertow (The UnderCity Chronicles) by Stelmack, S. M.

A Misty Mourning by Rett MacPherson