Reluctant Genius (54 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Alec would happily play with his grandchildren, as long as he knew he could retreat when he wanted. And while he left management of the estate to his wife, he insisted on complete control of his own work routines. Every year seemed to reinforce his obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Convinced that his physical surroundings induced specific trains of thoughts, he established particular workspaces for particular purposes. During the summers, he had three. In the little office near the laboratory on Beinn Bhreagh, recorded Daisy, “he occupied his mind with problems connected with the experiments; in his study in the house, he thought and worked over his theories of [flight]; while the

Mabel of Beinn Bhreagh

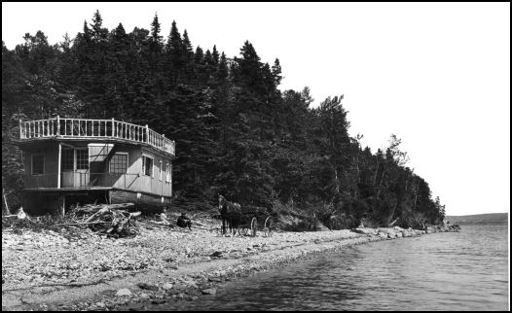

was the place to think of genetics and heredity.” By now, the houseboat in which he and friends had once cruised around Bras d’Or Lake had become unseaworthy, so it had been hauled onto the shore below the Point. Alec regularly retreated to its solitude from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning; there he would think, scribble down ideas, smoke his pipe, and subsist on baked beans and hardtack. On hot summer days, he would strip off and wade naked—“in

puris naturalibus,”

as he liked to say—into the lake. (On one occasion, he was sitting in his favorite state of nature on the houseboat roof when he realized he was in full view of a tour boat that was steaming up the lake, with a guide pointing out “the summer home of a great inventor.”) “Theoretically,” noted Daisy, “no one went near him when he was in retreat but actually John [McDermid, the coachman] always went down on Sunday morning to clear up, take provisions, lay a fire in the stove and bring back a report to Mother that Father was alright.”

Alec also clung to his nocturnal work habits. If seized by a brilliant inspiration in the middle of the night, he would frequently wake Mabel to tell her about it and ask her to take dictation so he could work on it the following day. Everything was grist for invention. One day, a beautiful and expensive set of venetian blinds, specially ordered from Italy, arrived at Beinn Bhreagh. But before Mabel had a chance to hang them, Alec had spirited them off to his laboratory to be transformed, with strong glue, into a spiral-shaped propeller. A few months later he couldn’t find any insulating material, so he suggested to his laboratory assistant John MacNeil that they rip up some carpets from the Point. Remembering Mrs. Bell’s face when she discovered the fate of her venetian blinds, MacNeil secured another source of insulation.

Mabel of Beinn Bhreagh: the beached houseboat where nobody was allowed to disturb Alec.

A young Baddeck woman named Catherine Mackenzie became Alec’s secretary on Beinn Bhreagh in 1914, and she soon learned that her boss was more than set in his ways:

In the office [near the laboratory] Mr. Bell had a small wooden table, cherry-stained, made by a local carpenter, with a drawer for his pipes and tobacco, a spare pair of spectacles and his reading glass… . The arrangement of this table was the same as that of his study table, and any change in its accustomed order annoyed him. There was a receptacle filled with birdshot, something like a wooden pyramid cut off 2/3rds of the way up, for pens and pencils. His lead pencils in the nearest corner, pen and red and blue marking pencils always in the same places and a piece of wire for a pipe cleaner stuck down the middle. Occasionally someone tidying up in my absence would fill up this holder with all the pens and pencils on the table, and when this happened it never failed to draw a “what are all these things doing here?” from Mr. Bell, and a rearrangement before he settled down to work.

Everything on Alec’s desk had its place, including the black inkwell, the red inkwell, the penknife, the tin of Dill’s Best Tobacco, the pipe cleaners, the bowl for spent matches, and the two pipes he always kept on hand (one to smoke and a cool one as a relay). The blotter hung on a particular hook, and the only ashtray he would use was one he had made himself from an old tin box fitted crossways with two metal bars. He would ritualistically bang out his pipe on the bars, “and he could bang out his mood in those raps more fluently than in words,” according to Catherine Mackenzie.

Bell employees quickly learned when they could and couldn’t disturb the boss. To break his train of thought was a cardinal sin: nobody was allowed to knock on the door. “If he was busy he paid no attention to the visitor, but if he had to interrupt his work to say ‘come in,’ or worse, if he had to rise to open the door, it annoyed him. The lab employees and the maids at the house were schooled in this, and luncheon trays were brought in and fires replenished, and so on, and unless spoken to Mr. Bell worked on undisturbed. But if there were many interruptions a big NO was printed on a sheet of paper and pinned on the study door, and then even Mrs. Bell dared not penetrate.”

Punctuation had its own rules in Alec’s papers. “Home Notes [a daily record of activity, separate from the Lab Notes] had to be taken always with the date, day and place at the top of the page. Mr. Bell was particular about the margin, the use of the colon, and underlining. He … had an antipathy to the use of the period after an abbreviation, it was ugly and a waste of space.”

Try as he might, however, Alec was far too impulsive a person to stick to the routines he prescribed for himself. He would announce that he was going to have breakfast at ten, dictate his Home Notes from eleven to twelve, drive to the office for one, be home at five. But within days, the schedule would collapse for any number of reasons—because his dictation had gone on too long, or he had become absorbed in the

New York Times,

or he had worked until dawn on a new idea, or there had been a midnight storm and he had been unable to resist rushing out in a swimsuit and rubber boots to enjoy the raging elements. “But he liked to have other people live on schedule,” according to Catherine Mackenzie. “He liked to have the regularity of life there to count upon and be independent of when he chose.”

Alec’s daily routines were as rigid during the winter months in Washington. There, too, he had three different workspaces: his study at 1331 Connecticut Avenue in which to do correspondence; the Volta Bureau in Georgetown, where he could focus on his work with the deaf; and a small hut in the Fairchilds’ backyard, overlooking Rock Creek, for more abstract thinking. “A sofa, a fireplace or stove, a box of shot in which he could stick his pens and pencils, a few pipe cleaners and a rug of some kind to throw over him were all the material comforts which Mr. Bell ever required,” recalled David Fairchild. “But the most important thing of all was quiet.”

When Mabel was absent, Alec’s eccentricities went uncurbed. During a heatwave early one year in Washington, a reporter turned up to interview the inventor of the telephone. He was asked to return later, but when the reporter suggested six or seven that evening, the inventor replied, “Oh no, nothing before 11. You could come at 11, or 12, or 1, or 2 at night and we’ll be quiet and I’ll be very glad to see you.” When the reporter returned at midnight, Alec answered the door clad in a long dressing gown fastened around his ample girth with a length of cord. He ushered the reporter into the pantry with the words, “Mrs. Bell is always very careful about what I eat, so we’ll just raid the icebox and get something good to eat.” After he had gorged on such forbidden delights as ham and buttered toast, he informed the reporter that they would move on to the swimming pool.

The reporter protested that he did not have a swimsuit. “Oh, you don’t need a bathing suit,” Alec replied. “There is no water in the tank. It is just an experiment that I am making in cooling the house, as it seems to me it is just as sensible to cool a house in summer as it is to heat it in winter.” The two men proceeded down the back stairs of the house into a concrete tank, at the bottom of which, according to Daisy Fairchild’s account of the incident, “[m]y Father had a rug, a writing table with a student lamp on it, and two comfortable chairs in it.” In an era before either refrigerators or air-conditioning had been invented, Alexander Graham Bell had put an icebox in a third-floor bathroom and then installed a fan that blew the cold air from the ice down through a canvas firehose into the swimming pool. “Of course,” added Daisy, “he didn’t mention the big expense involved.”

The demise of the Aerial Experiment Association left a vacuum at Beinn Bhreagh. Casey Baldwin, along with his wife, Kathleen, remained in Baddeck, and he continued to work on flying projects with Alec. At one point, it had seemed possible that the Canadian government was interested in the aviation experiments of the famous Dr. Alexander Graham Bell. He was invited to travel to Ottawa in March 1909 and speak to the Canadian Club at the Chateau Laurier Hotel. Mabel encouraged him to accept the invitation: “The Govt. may take over the whole expense of further experimenting with the

Silver Dart

and the engine and we may evolve something for the

Cygnet”

The following August, Casey and Douglas McCurdy took their latest biplane prototypes

(Baddeck No. 1

and

Baddeck No.

2) to Ottawa for military trials. But the trials were held on a bumpy cavalry field, both planes were wrecked, and Mabel’s hopes died with them. Alec returned to his lonely (and doomed) crusade to prove that kites constructed from tetrahedral cells had as much potential as biplanes for powered, manned flight.

Yet Alec’s fertile mind was already going in a new direction. “Why should we not have heavier than water machines as well as lighter than water?” he had asked himself in 1906, after an article about hydrofoils had appeared in

Scientific American.

An American hydrofoil pioneer explained in the article the basic principle of hydrofoils: plates or blades that would act in water the same way that airplane wings act in air. As a craft fitted with hydrofoils gathered speed in water, the submerged hydrofoils would lift the hull until it left the water entirely, and the vessel would then skim along the surface. In 1909, soon after the Cape Breton flights of the

Silver Dart,

Alec and Casey started building hydrofoils, or “hydrodromes”as Alec insisted on calling them. But disaster dogged attempts to launch their early prototypes, which looked like clumsy rafts with large wooden propellers mounted above the stern. As soon as the vessels achieved any speed on Bras d’Or Lake, they collapsed into a mangled mess of wooden supports and jerry-built propellers.

It was time for a change, and Mabel suggested her favorite remedial activity: international travel. In 1910, the Bells and the Baldwins set off for a year-long world tour—a tour that did wonders for Alec’s morale. “One of the nice things,” Mabel wrote to her daughters from New Zealand, “is the way so many perfect strangers have come to say how glad or honored they are that Papa should come to their country.” The inventor of the telephone was acclaimed everywhere. An Australian reporter described Alec as “one of the two most interesting visitors Australia has ever had from the United States” (Mark Twain was the other). In China, the Bells and Baldwins were invited to an official lunch in the new Foreign Office in Beijing, and feted with fried silver fish, shark’s fin soup, Yunnan ham, bamboo sprouts with caviar, pheasant, roast duck, and cakes with almond sauce. (The shark’s fin soup left Alec cold: he was much more interested to see the popularity of the telephone in China, where the profusion of Chinese characters had rendered the telegraph too unwieldy.)

Alec never really enjoyed meeting strangers; a few years later, Mabel recalled the “determination he showed to escape any [invitations] while we were in Australia.” But he did agree to visit the Melbourne home of Marie McBurney, née Eccleston, to whom the young Alexander Graham Bell had proposed in London forty years earlier. Recently widowed and struggling to support herself by giving music lessons, Marie McBurney impressed Mabel as a “bright, plucky, energetic woman.” In India, the party sent off their first airmail letters in a tiny, rickety airplane at Allahabad; the plane hopped bravely across the Ganges and landed the mailbag on the opposite bank.

But Alec’s mind still raced with new ideas and new approaches to old ideas. All the way across the Pacific, he experimented with composite photography and made schematic representations of his sheep studies. He studied the soaring flight of albatrosses as the party steamed from Australia to New Zealand, pointing out to Casey how their heavy heads and short tails contradicted all the latest theories about manned flight. He noted plants and insects that he saw for the first time (the stinging tree, the lawyer vine). In the South Pacific, he was fascinated by the speed and efficiency of outrigger canoes and immediately began making sketches of catamaran hulls he intended to build in Cape Breton. Everywhere he went, he visited institutions for the deaf and collected government publications about educational methods, infant mortality, natural resources, rainfall. And he continued to ruminate about flying machines.

Alec’s interest in such machines finally found an outlet when the party reached Europe. In Monte Carlo, he and Casey were intrigued to see flat-bottomed hydroplane boats roar noisily across the blue water of the Mediterranean. They were even more excited to see, on Italy’s Lake Maggiore, similar vessels designed by the Italian engineer Enrico Forlanini speed across the water with much less commotion than the Monte Carlo boats. The enthusiastic Signor Forlanini insisted that the great American inventor and his assistant take a demonstration ride. Alec, who never rode in any of the contraptions produced by his own laboratories, was nervous, but too polite to decline. “Both Father and Casey had rides in the boat over Lake Maggiore at express train speed,” Mabel wrote to Elsie. “They described the sensation as most wonderful and delightful. Casey said it was as smooth as flying through the air. The boat… at about 45 miles an hour glides above the water… being supported on slender hydro-planes which leave hardly any ripple.”