Reluctant Genius (52 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

“In scientific experiments,” Alec believed, “there are no unsuccessful experiments. Every experiment contains a lesson. If we stop right here, it is the man that is unsuccessful, not the experiment.” The lesson from the

Red Wing

was that a biplane needed a better system to ensure horizontal stability and prevent roll than simply a shift of weight by the pilot. “Movable wing tips,” suggested Alec, who had noted years earlier that some birds altered the angle of their wing feathers in flight. Casey Baldwin incorporated this suggestion in his biplane, the

White Wing

(white cotton muslin had replaced the red silk). The

White

Wing’s wings had hinged tips, attached by wires to the pilots seat. Casey controlled these devices, called “ailerons,” by leaning in the direction he wished the plane to go. The plane also boasted another innovation: a tricycle undercarriage for takeoff and landing on solid ground. By now Lake Keuka was no longer frozen, so this plane needed to take off from an old abandoned racetrack outside town. The track was partly covered in grass and uncomfortably close to a potato patch and vineyard.

Obsessed as always by safety, Alec was extremely nervous: “[T]he machine is distinctly of

the dangerous kind.…

[T]he young men here are prepared to take risks.” He longed for Mabel’s calm presence at his side (“I feel

awfully lonely”)

and confided to her, “[F]or my own part, I should prefer to take my chances in a tetrahedral aerodrome, going more slowly over water. However, I have not the heart to throw a damper over the ambitious attempts of the young men associated with me.” Thankfully, there were no mishaps. Between May 18 and 23, when Douglas McCurdy crashed the

White Wing,

all four young men successfully flew it.

The race to fly was now the biggest story in North America. In the fall of 1907,

Scientific American

had offered a trophy for the first public flight over a measured course of one kilometer. Charles Munn, the magazine’s publisher, hoped to lure the Wright brothers into a public demonstration of their aircraft—they were being widely challenged to prove they were either “flyers or liars.” The Wrights were way ahead of their competitors: they had already developed a way to make their Flyers turn to left and right, as well as fly in straight lines. But they had not yet developed a wheeled plane that took off under its own power. Their machines were launched from a track, propelled forward by a cable and pulleys attached to a half-ton weight that was dropped from a tall derrick. And despite Munn’s nudging, they spurned the opportunity to participate in the

Scientific American

race because of their fear of copycats. This left the field clear for every other aviation pioneer on the continent to dream of winning the coveted trophy—an elaborate silver sculpture of an airplane circling the globe, on a pedestal ringed by flying horses.

Bell’s Boys were eager to go for it. The AEA’s obvious candidate was the fourth biplane it had developed: Glenn Curtiss’s

June Bug

—named, Mabel told her mother, “because Alec said its wings resemble those of an insect in flight and it is to fly in June.” Both Alec and Mabel were in Hammondsport to watch Curtiss take the little plane through its early test flights, but they did not stay long; as usual, Alec was determined to return to Cape Breton. He agreed, though, that his boys should continue their aviation experiments in Hammondsport, and that the

June Bug

should be entered for the

Scientific American

trophy.

That summer, Hammondsport racetrack had a carnival atmosphere, as flying-machine buffs, schoolboys playing truant, and cranky inventors milled about. The inventors all learned technical tricks from each other. Although the Wright brothers had patented a version of ailerons two years earlier (they called their system “wing warping”), most people saw them for the first time on the

White Wing.

For his part, Alec had been fascinated by a Mr. Myers, “the inventor of an Orthopter (or Ornithoper)—a machine akin to the beating-wing type, but which does not operate by beating wings.… ‘The boys’ call it the ‘Wind-grabber.’” Each day, various flying machines were trundled out to wait for either a good wind (for kites) or no wind (for powered biplanes). A pack of reporters did not dare visit the local town, “even to eat, for fear they might be absent at the critical time.”

After days of waiting for the right conditions, Curtiss took the

June Bug

up on the Fourth of July 1908. David and Daisy Fairchild were among the crowd that clustered around the aircraft before takeoff. It looked such a fragile contraption, with its vast yellow wings of fabric and bamboo atop three rickety bicycle wheels, and the forty-horsepower motorcycle engine behind the pilot’s seat. The top set of wings arched gently down, while the lower set arched upward. A new feature of this machine was that the wing fabric had been soaked in a mixture of paraffin, gasoline, turpentine, and yellow ocher, to reduce air resistance. (This “doping” dramatically increased the little plane’s lift and was incorporated into all subsequent machines that employed cloth wings.) A frowning Curtiss was perched on a seat in the middle, with the whirring propeller in front of him, as the biplane trundled down the runway. Liftoff seemed at first impossible, as the tricycle wheels rumbled over the stony ground; then, as Curtiss pulled on the front “lift” control, it happened almost effortlessly.

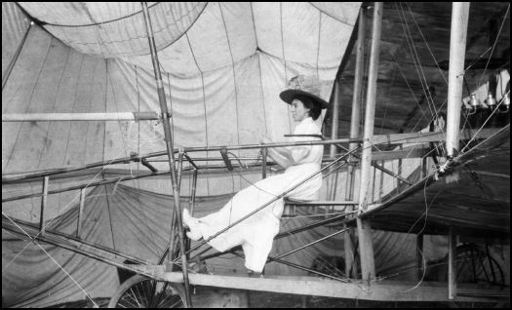

At Hammondsport, New York, Daisy Fairchild posed in the June Bug before it was trundled out of its hangar.

Against the pale gray of the evening sky, the

June Bug

rose thirty feet above the ground. Curtiss’s hair streamed out behind him as the flimsy little plane hurtled forward, straight toward the finish line. Daisy was ecstatic at her first glimpse of “a man flying through the air.” She wrote to her father, “As Mr. Curtiss flew over the red flag that marked the finish and way on toward the trees, I don’t think any of us quite knew what we were doing. One lady was so absorbed as not to hear a coming train and was struck by the engine and had two ribs broke.… We all lost our heads and David shouted and I cried and everyone cheered and clapped and engines tooted.”

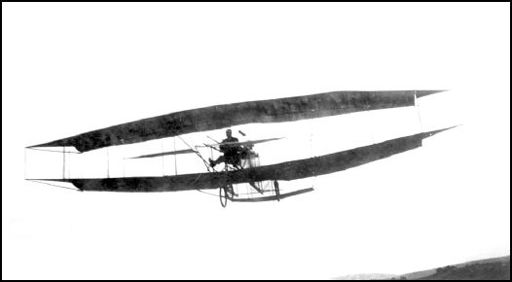

Victory! The June Bug, piloted by Glenn Curtiss, wins the Scientific American trophy in 1908 for being the first flying machine to fly one kilometer in a public demonstration.

Curtiss had flown 5,090 feet—just short of a mile, or 1,810 feet more than the

Scientific American’

s specified distance of a kilometer. His flight took the coveted trophy. The Wright brothers might have achieved the first manned flight, but Alexander Graham Bell’s AEA had won the first

Scientific American

trophy. It was a huge achievement. Bell’s Boys did what the Wrights had failed to do: they finally convinced the world that human flight—the dream of centuries—was real.

Bell’s Boys were on a roll. Casey Baldwin agreed to return to Baddeck, to help Alec with the next generation of tetrahedral kite. Douglas McCurdy stayed in Hammondsport to work on his flying machine, which, since its wings were covered in a silvery waterproofing material, was already nicknamed the

Silver Dart.

“All the A. E. A. have learned a lot from the Hammondsport machines,” Mabel told her mother, and they were all eager to challenge the Wrights’ machines in the next competition.

But then tragedy struck. Tom Selfridge had been appointed to the U.S. military board that was conducting trials of the Wrights’ planes, with a view to offering them what they had sought for years: a lucrative army contract. On September 17, 1908, Tom volunteered to be Orville Wright’s passenger on a required two-man flight at Fort Myer, an army base in Virginia. Everything appeared fine at first—“Wright could be seen, hands on levers, looking straight ahead, and Lieutenant Selfridge to his right, arms folded and as cool as the daring aviator beside him,” reported one observer. Suddenly, after four minutes aloft, during which the plane circled the airfield, there was a loud crack, and a piece of the propeller blade flew off. The plane shivered, then nosedived into the parade ground. The engine tore loose and thudded into the earth. Dust exploded like the burst of a mortar shell. Orville Wright was badly injured; Thomas Selfridge never regained consciousness and died later that day. He had the melancholy distinction of becoming the first person to die in an airplane accident.

The Bells were devastated. “I can’t get over Tom being taken,” Mabel wrote to her mother. “Isn’t it heart-breaking?” She had always cared about all four young men in the AEA, but Tom was the one who went out of his way to care for

her,

looking after her “in a hundred little ways I have never been looked after before.” The loss of Tom deeply depressed Alec, who had always been so conscious of the risks of flying. “I am still quite stunned by the news from Washington,” he confided to Mabel.

There was one more success ahead for the Aerial Experiment Association. Mabel Bell had extended the life of the association’s original agreement by a further six months and by an investment of a further ten thousand dollars. Douglas McCurdy completed his

Silver Dart

and shipped it to Beinn Bhreagh. On February 23, 1909, the little biplane was wheeled onto the ice of Baddeck Bay. Baddeck townspeople streamed onto the ice to watch Dr. Bell’s latest madness; they stroked the little plane’s silver wings with mittened hands, watched Douglas as he checked the machine, and pulled their woolen coats tighter against the winter wind that was tearing down St. George’s Channel. Then John McDermid, the Bell’s coachman, cranked the propeller and Douglas revved the engine. When it had reached top speed, he put the engine in gear and tore down the lake, followed by a crowd of schoolboys on skates. Once the

Silver Dart

took to the air, the schoolboys were left far behind. In the crisp winter air, the machine twinkled like a brilliant gem in the sunlight as it roared off, at forty miles an hour, then turned and completed a flight of more than half a mile.

Piloted by Douglas McCurdy, the Silver Dart soars over Bras d’Or lake in February 1909.

A cheer had arisen from the crowd below, but nobody’s grin was wider than Alexander Graham Bell’s. Knowing that the Wrights had already achieved this distance and speed in the United States, Alec reverted to his British origins as he declared that this was the first heavier-than-air flight by a British subject in the British Empire. Then, flinging his arms wide open with characteristic generosity, he invited everybody present back to Beinn Bhreagh for sandwiches, coffee, and raspberry juice made from berries that grew wild on the headland.

The

Silver Dart

incorporated every piece of knowledge then available about aviation. By now the Bell team had developed the technology required to fly the plane in circles. The next day, Douglas covered more than four miles in a flight around the bay. In this rugged, ravishing corner of Canada, aviation history was made. Over the next month, Douglas would make thirty more flights across Bras d’Or Lake. “Silver Dart Flies for Eleven Minutes,” reported the

New York Times

on March 9, 1909. “Dr. Bell’s Flying Machine Covers Twelve Miles in Circular Course. Hopes to Beat Record.”