Reluctant Genius (47 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

The death of his father-in-law had a second, more onerous impact on Alexander Graham Bell. Without its founder, the National Geographic Society began to wobble. Membership had stalled, its journal was boring, and its debts were growing. Alec had little interest in this dull little Washington club, but both Mabel and her mother were determined that Gardiner Hubbard’s creation must survive. Despite his misgivings (and a dread of getting tied down more firmly in Washington), Alec buckled under their pressure and agreed to become the society’s second president. In the first months he watched its membership decline to less than a thousand, and glumly acknowledged he had to find a way to give the society a new lease on life. Since the money-losing journal was, in his words, something that “every one put upon his library shelf and few people read,” he decided to relaunch it as a much more popular publication. It would be the hook to bring new members into the society. Two of his favorite periodicals were

McClure’s

and the

Century

(both had carried articles about him)—he liked their choice of material and their lively writing. The new

National Geographic Magazine

would have as its slogan, “The world and all that is in it.” But he wanted to add an additional element: lots of good illustrations and photographs— pictures of life and action,” he explained. “Pictures that tell a story!”

The first requirement for the new magazine was a full-time editor. Alec dug into his own pockets, as he had for

Science

in the 1880s. He announced to the society’s board that he would underwrite for the first year a monthly salary of $100 for an editor. Then, urged by Elsie, he persuaded young Gilbert Grosvenor—always known as “Bert”—to quit his teaching job in New Jersey and start work as the National Geographic Society’s first full-time employee on April 1, 1899. Once Gilbert started work in the magazine’s one-room office at 1330 F Street, Alec was a fount of support. When he heard that the new editor had found the room “a perfect pigsty,” with paper all over the floor, dust everywhere, and a spittoon but no desk, Alec sent over his own rolltop desk from Connecticut Avenue. He bombarded Gilbert with ideas for articles; the list included China’s influence in the Philippines, polar exploration, Spanish earthquakes, waltzing mice, waves, and auroras. He urged Gilbert to write personal letters to newspapers, suggesting to editors that they review the new publication. Every issue of the magazine included a blank subscription form—the first time such a tactic, dreamed up by Alec, had ever been used.

Bert must have found his proprietor’s enthusiasm rather suffocating. But if he did, he kept his cool—particularly since he enjoyed his visits to the Bells’ Washington household. Bert had become a fixture there, always happy to make up the numbers at dinner and to escort Elsie to events. One evening, Mabel watched as Elsie flirted with Bert. She held his hand, teased him for being “so sweet,” and put her own hand on his knee when she casually leaned over him to speak to her mother. Bert sat silent, smiling but unresponsive. “They are evidently extremely good friends,” Mabel reported to Alec. But Gilbert’s stolid, throttled-back style was certainly at odds with the passionate courtship Mabel had experienced from Alec. “Is it possible for a young man in love to be so perfectly self-possessed when his lady-love is around and near him?” she mused. “I am sure you weren’t.” Mabel was not thrilled by Gilbert’s prospects, either. She felt that Elsie was “fitted for a more brilliant position than Gilbert can give her,” she confided to a friend: a penniless young man employed by her husband was not her dream son-in-law. “It will never do for her to marry a poor man and have to live in a small house,” she wrote, “yet she seems drifting that way.”

Mabel had expected that the National Geographic Society would force Alec to spend more time in Washington, where he might mingle with eminent scientists as well as spend more time with his wife and children. He might even, she hoped, pursue money-making inventions in the little laboratory he still maintained behind his father’s Georgetown house. But Alec had other ideas: his priorities did not include his daughter’s flirtations, the society’s day-to-day health, or Mabel’s social ambitions. A new note of urgency had crept into his ruminations about flight: “Every bird that flies is a proof of the practicability of mechanical flight by objects heavier than air.” He was not alone—even the U.S. War Department was getting interested in man-carrying flying machines. In 1898, when the United States went to war with Spain over Cuba, the American military brass started to put money into Samuel Langley’s aerodromes. Alec hungered to keep abreast of his friend and to have one more grand invention in the years ahead. “The more I read of the war news, the more I realize the importance of a flying machine in warfare,” he wrote. “Not only for scouting purposes—but for actual offensive work…. I am not ambitious to be known as the inventor of a weapon of destruction but I must say that the problem, simply as a problem, fascinates me.” He had already decided that, unlike most other American aviation enthusiasts, he was going to explore the potential of kites rather than winged machines. He had established a kiteflying station on Beinn Bhreagh’s highest point. Now he ached to head north to the headland’s windy slopes, so he could continue his investigation of the airborne characteristics of kites.

Alec didn’t have to wait long. Within a year of Bert’s arrival, the number of subscribers (always known as “members” within the society) to the

National Geographic Magazine

had almost doubled. Confident that the redesigned magazine was in good hands, Alec returned to Cape Breton. Once back at Beinn Bhreagh, he resumed his correspondence with Mabel. There were continued mentions of his sheep, and from time to time he left Cape Breton to attend deaf-education conferences and visit schools for the deaf. But the dominant theme was kites. He built kites shaped like stars, large cylindrical kites, big round kites. He built a box kite, resembling a box that had had both ends and a section of the middle removed, that was

huge:

fourteen feet long and ten feet wide—“a monster, a jumbo, a full-fledged white elephant.” (His description was correct: he and Ellis had to remove a wall of the laboratory in order to get the kite outside, but they never could get the monster to fly) His most interesting innovation during this period was the idea of constructing kites out of tetrahedrons: four equilateral triangles joined together to form a pyramid. The cells could be arranged in twos or threes or thousands. Kites constructed out of several of these cells were lighter and less wind-resistant than more conventional kites. The sight of all these weird and wonderful shapes aloft in the Cape Breton skies prompted one boatman, who was rowing a visitor across to Beinn Bhreagh, to describe Mr. Bell’s experiments as “the greatest foolishness I have ever seen.”

Alec’s ring kite proved surprisingly airworthy.

Alec admitted to his wife that building a manned flying machine (he and Langley persisted in calling their machines “aerodromes”) “will be an expensive thing to construct, quite apart from the money that must be sunk in abortive experiments.” But he tried to persuade Mabel—and himself—that his obsession with kites could well pay off financially. “Suppose a new form of flying toy—or kite—could be put upon the market…. There might be money enough made from the toy to build an actual machine.” Hoping to convince his wife that these weren’t castles in the air, he argued that if only a quarter of America’s seventeen million children bought such a kite, he could raise as much as $100,000.

Mabel gently inquired in one letter how he was getting on with drafting his presidential address for the

National Geographic Magazine.

Her question triggered an outburst of frustration. Alec could barely stop his hand shaking as he sat at his desk upstairs in Beinn Bhreagh, and wrote back, “Simply can’t do it!!” He considered all his unfinished projects. Ever since they had rushed down to Washington when Gardiner Hubbard was dying, he complained, he had been unable to achieve anything: “I will not give up my work again excepting for matters of

life and death.

I have given up too much of my time already. I am no longer young, and the experiments on which I have been engaged for years should be completed sufficiently for publication…. I am sick at heart when I think of the waste of my life and ideas during the last year.”

In vain, Mabel argued that Alec’s daughters still needed him to accompany them on another trip to Europe to widen their experience and social circle. “They have not had the opportunities that most other girls of their position have. They do suffer from having a deaf Mother, and a Father so absorbed in his work that he won’t go out and make friends for them. They have had to do the best they could almost alone.” She urged him to rethink his priorities. “Are you willing that Elsie should drift into an engagement with Gilbert without further opportunity of seeing other men? … Elsie and Daisy are also works of yours…. You started them before you started aeronautics so they ought to be finished first!” Alec was adamant. Convinced he was wasting both time and inspiration, he begged, “Don’t ask me to spend my summer abroad this year. I cannot do it.” She, the girls, and “Charles the faithful” were welcome to go abroad; he would not leave Baddeck.

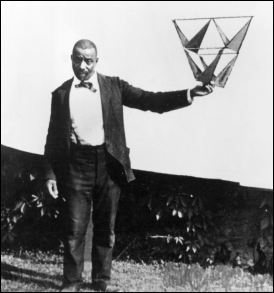

Charles Thompson holding a tetrahedral construction.

Mabel knew when she was beaten. She could see that Alec would be miserable anywhere but at Beinn Bhreagh because he was so determined to be part of the race to build a flying machine. And she also knew that only on Beinn Bhreagh was Alec capable of relaxing and enjoying his family at the same time as he built bigger and better kites. So she changed tactics and arranged for the whole family to spend the summer of 1900 in Baddeck and enjoy visits from an endless stream of friends and relatives.

Among the visitors was Dr. Simon Newcomb, the irascible director of the American Nautical Almanac with whom Alec often dined in Washington. Nova Scotia-born Newcomb was a brilliant mathematician and astronomer who had never graduated from a university. Since his career path so closely mirrored that of Samuel Pierpont Langley, one might have imagined that the two men were friends. But nothing could be further from the truth: rivalry crackled between them. Mabel was appalled to discover that, somehow, the two Washington scientists were scheduled to stay at Beinn Bhreagh the same week. Alec, however, just chuckled.

It was a Beinn Bhreagh ritual for the family and guests to spend the early evening lounging on the comfortable wicker furniture on the sunporch, gazing at the patterns that breezes made on the lake. During the Langley-Newcomb week, however, the preprandial conversation was anything but amiable. The two men just couldn’t stop arguing. “It was very amusing to Mr. Bell,” Charles Thompson would recall after Alec’s death, “to sit and listen to those two great scientists discuss both sides of a given subject, often very heatedly.” Alec often disappeared into the library next door when the two men started squabbling, but Charles would find him still in earshot, “holding his sides with laughter.” One day, a fierce argument arose between Langley and Newcomb as to whether a cat would always land on its feet when in free fall, even if it was upside down when it was dropped. Langley insisted it always happened; Newcomb said that was ridiculous. “Here’s a good chance for an experiment,” said their host. “Let’s try it.” Charles was dispatched to “round up some cats,” as Elsie recalled years later, while she and Daisy rushed around and found mattresses and put them under the porch. Newcomb was ceremoniously presented with a kitten: he held it upside down, squalling and squirming in discomfort, over the balustrade and dropped it. Somehow, it landed on its feet. Newcomb hurrumphed that this was “an accident.” Charles was quickly summoned. “I had to recapture [it] a dozen times or more,” Charles remembered. “But the cat’s landing on its feet every time did not end the discussion, it only added fuel to it.”

How Alec loved such exploits at Beinn Bhreagh! Mabel watched her husband laugh as he puffed away on his pipe (he had finally abandoned his cigar habit in 1898, when Mabel pointed out it was costing more than sixty dollars a month). She realized he would never be the intellectual leader within Washington society that her father had been and she had always hoped her husband might become, so she didn’t take the girls to Europe. By the end of the summer, Elsie had accepted a proposal of marriage from Bert, and Mabel had welcomed Bert into the family as warmly as her own mother had welcomed Alec. Mabel had accepted that, if Alec would not go off and mingle with men of science in the metropolis, the men of science would have to come to him, in remote Cape Breton.