Reluctant Genius (59 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

But Mabel herself was starting to flag. “I have my hands full of things I want to do for Father and I have not much energy, it takes a long time to get anything done,” she confided to Bert Grosvenor. Her world was shrinking in every way. She was having great difficulty in making out what people were saying, because her sight had started to deteriorate. Neither of her daughters or anybody else in the family knew the manual language that Alec had sometimes used with her. As the reality of isolation bore down on her, the darkness created by Alec’s death became more and more oppressive. What was left for her to live for? She missed her husband dreadfully; she wept copiously, wretchedly, miserably. Her daughters realized that their mother was suffering more than normal grief.

On Beinn Bhreagh’s mountaintop, a brass memorial tablet marks Alec’s and Mabel’s graves.

When Mabel returned to Washington in December, she finally saw a physician. He told her that she had a terminal form of pancreatic cancer. She was almost relieved to hear the diagnosis. “Wasn’t I clever,” she remarked to Daisy, “not to get ill until Daddysan didn’t need me anymore?” She died only days later, on January 3, 1923, five months after Alec. Below the headline “Widow of Inventor Is Dead,” the

New York Times

reported that “[t]he recent death of her famous husband affected Mrs. Bell’s health. Since the day the inventor was buried in Nova Scotia, his widow has been grieving. She never recovered from the shock, it was said today.” The Associated Press report, widely republished, was blunter: “Mrs. Bell passed away after a long illness beginning with a breakdown suffered at the time of Dr. Bell’s death last August.”

Mabel Bell’s funeral took place at Twin Oaks, once her parents’ home, where her last surviving sister Grace now lived with her husband (and Alec’s cousin) Charlie Bell. The following summer, exactly one year after the funeral of Alexander Graham Bell, Mabel’s son-in-law Gilbert Grosvenor placed her ashes in the grave beside him on Beinn Bhreagh.

A large rock, with a brass memorial tablet on it, now marks the final resting place of both Bells. The symmetrical inscriptions on the memorial reflect the balance and harmony of their relationship. On the left-hand side, the tablet reads, “Alexander Graham Bell, Inventor Teacher, Born Edinburgh March 3 1847, Died a Citizen of the U.S.A., August 2, 1922.” On the right-hand side, it reads, “Mabel Hubbard Bell, His Beloved Wife, Born Cambridge Mass, November 23 1857, Died Washington D.C., January 3 1923.”

Nearly a century after the deaths of Alexander Graham Bell and his wife, the headland they loved so dearly remains undisturbed—still owned and visited every year by their many descendants. Today, in front of their grave, Bras d’Or Lake sparkles in summer sunshine or glitters in winter frosts. The Cape Breton bald eagles soar above it, riding the air currents with effortless majesty.

“An inventor,” Bell once remarked, “is a man who looks around the world and is not content with things the way they are; he wants to improve what he sees; he wants to benefit the world.” Alexander Graham Bell was such a man.

Epilogue

T

HE

L

EGACIES OF

A

LEXANDER

G

RAHAM

B

ELL

A

lexander Graham Bell’s greatest invention changed the world forever. If Samuel Morse’s telegraph shrank geography, by compressing distance, Bell’s telephone liberated the individual because it allowed the transmission of a human voice. Almost all the inventions and technologies of the Industrial Revolution—steam engines, machine tools, mining equipment, microscopes, textile machinery—required special training in their use, and in some cases could be dangerous to their operators. But the telephone was easy and safe to use, and, unlike the telegraph, anybody could use it. It had a profound impact on both personal relationships and the social fabric of society. No wonder Stalin vetoed the idea of a modern telephone system in Russia after the revolution, according to Trotsky’s

Life of Stalin.

“It will unmake our work,” said the dictator. “No greater instrument for counterrevolution and conspiracy can be imagined.”

The effect of Bell’s invention on business, commerce, industry, politics, and warfare in the early twentieth century was instant and quickly self-evident. Thanks to the telephone, generals could stay in contact with field officers, an architect could confer with a foreman straddling a girder hundreds of feet above him, politicians could rally supporters during elections. The telephone has been blamed for urban sprawl (buildings no longer had to be within walking distance of each other for ease of communication) and credited with suppressing crime (police officers could summon help). In rural areas, the early party-line system created a virtual community, as farmers gathered by their phones each evening to exchange news and gossip. At Beinn Bhreagh, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the telephone’s inventor quickly learned to be discreet on the party line that Alec Bell himself had rigged up between various houses and offices on the estate. “Aunt Daisy loved to listen in to our conversations,” recalled Dr. Mabel Grosvenor, aged one hundred in 2005 and the Bells’ last surviving grandchild. “If the conversation got too personal, we’d hear her voice: ’Don’t forget, I’m here!’”

By the early decades of the twentieth century, the telephone was entrenched in popular culture and literature. Songs with titles like “Hello, Central, Give Me Heaven” and “All Alone by the Telephone” became parlor favorites in an era when every home had a piano. Telephone calls crop up in two of the masterpieces of modern literature: James Joyce’s

Ulysses,

first published in 1922, and Marcel Proust’s

Remembrance of Things Past,

published from 1912 to 1922. The telephone came to loom so large in stage plays that, as writer John Brooks has pointed out, “the telephone onstage became the leading cliché of Broadway.” And we can all list movies in which the telephone has a starring role, from the 1950s classics like

Dial M for Murder

and

Pillow Talk

to more recent releases such as

Legally Blonde,

in which cellphones seem to be glued to the ears of the main characters.

The telephone challenged existing technologies (local mail service lost business), existing hierarchies (France was slow to develop a phone system because the state controlled access), and existing employment patterns. The demand for “hello girls,” as switchboard operators were known, opened a vast new field of white-collar employment for women.

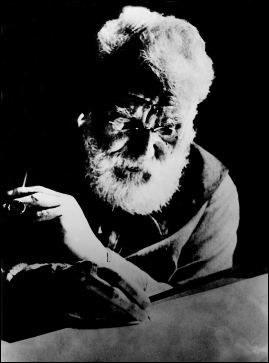

Genius at work.

By the time Bell himself died, a continental web of telephone wires, suspended from telephone poles for which whole forests had been razed, covered North America and Europe. And that was all before technology took another leap forward, with the introduction of wireless service. Today, a world without instant voice communication to any point on the globe is, for most of us, inconceivable.

Alexander Graham Bell is far more than his telephone. But this one device says so much about his genius—it evolved from his determination to help the deaf; a process of intuition, rather than calculation, prompted the crucial conceptual breakthrough that allowed him to transform electric impulses into sound; and once he had made that breakthrough, he was eager to move on to other things. Bell’s gift as an inventor was creative leaps of the imagination rather than the rigorous research that characterized such contemporaries as Thomas Edison. Wealth and fame were important to him only insofar as they freed him up to

think.

For the rest of his life, he was a spectator on the industry he had spawned, as others transformed the telephone into an effective instrument by means of marketing and technological improvements such as automatic switchboards and multiplexing systems that can send many conversations simultaneously over a single pair of wires. His patents and his family’s stock in the Bell Telephone Company made him rich, but he showed little interest in subsequent advances in the technology.

But Bell ached to be more than a one-hit wonder. What of his other inventions? What about the patents he received for the photophone, the graphophone, tetrahedral cells, flying machines, and hydrodromes? Did any of these leave a lasting mark on the world, or make him any money?

The patents that Bell and Sumner Tainter received for the graphophone yielded some capital for the Bells, when Thomas Edison purchased the patents in order to work on a device that recorded sound. The Edison phonographs, as early record players were known, owed some of their technology to Bell’s work, but it was Edison rather than Bell who got rich from them. The technical breakthroughs achieved by the Aerial Experiment Association were incorporated into subsequent flying machines, but the Wright brothers had done most of the groundbreaking work on early airplanes. The AEA patents did have a small payoff to Alexander Graham Bell, when Glenn Curtiss purchased them for $5,899.49 in cash and $50,000 in Curtiss stock in 1917, but Mabel Bell always felt that Curtiss had cheated them, because Curtiss turned around and sold all his patents, of which the AEA ones were considered the most valuable, to the United States government for a reported $2 million, and kept all the proceeds.

The rest of the patents granted to Alexander Graham Bell and his associates—the patents for photophones, tetrahedrals, and hydrodromes—expired before anyone showed much interest in them. Yet the technologies they described would all be exploited in subsequent years. In 1957, Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow developed the laser for Bell Laboratories, and in 1977 the Bell Corporation installed under the streets of Chicago a fiber-optic system that carried digital data and voice and video signals on pulses of light. Tetrahedral kites never justified their inventor’s faith in them as manned flying machines, but the American architect, engineer, and poet Buckminster Fuller popularized tetrahedral construction in 1957 when he constructed his first geodesic dome. Today, several large structures employ the technology—the retractable roof of Toronto’s Rogers Centre stadium, for one, relies on tetrahedral construction. And the research done by Alexander Graham Bell and Casey Baldwin on hydrofoils was the foundation for the development of various naval prototypes after the Second World War. Canada’s Defence Research Board built a spectacular vessel and named it the

Bras d’Or

in memory of Bell. These days, commercial hydrofoils operate on inland and coastal waterways around the world, particularly in Japan and Russia.

In 1997, when I first visited the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, I was immediately intrigued by both Bell and his wife. As I entered the building, I was confronted first by a huge photo of Dr. Bell, bearded and benevolent, and next by a picture of a long-skirted Mabel Bell, with an expression that was both girlish and maternal. I was hooked. I wanted to understand how he invented the telephone, but I also wanted to find out why he had left Scotland, what had propelled him to marry a woman so different in age and background, whether she had played an important role in his life, and how he came to build a research laboratory in one of North America’s most remote corners. When I set out to write about Alexander Graham Bell a couple of years later, I was determined to write more than a biography of an inventor. I wanted to explore his life within the context of his family relationships and of the ferment of the late nineteenth century.

During the years that I have spent in the company of this man, I have discovered a much more neurotic and unconventional individual than I had expected. I have come to realize his incredible dependence on his wife, Mabel Hubbard Bell. Brilliantly intuitive in his research, Bell could be demanding and insensitive to those he loved. Mabel Hubbard was a warm-hearted, clever woman who had to make all the compromises and sacrifices in their marriage. Yet, as I traced the Bells’ relationship through their journals and letters, I saw a wonderful love affair, in which each partner supplied what the other most needed. Mabel gave Alec stability and a safe haven in which he could pursue his obsessions. Alec ensured that Mabel, far from being shoved to the margins of speaking society like most deaf people in her day, had an exhilarating and challenging life. When Alec predeceased his wife, her world collapsed. Maybe cancer was the word on Mabel Bell’s death certificate, but those around her all knew that she died of a broken heart. As the Bells’ granddaughter Dr. Mabel Grosvenor observes, “[s]he was the center of the family for the rest of us, but everything she did was for him.”