Reluctant Genius (56 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Chapter 21

T

HE

L

AST

H

URRAH

1915–1923

T

he outbreak of war in Europe in September 1914 had presented Alexander Graham Bell with a painful dilemma. He was torn between loyalty to the British Empire, which was at war and in which he spent his summers, and to the United States, of which he was a citizen and which remained resolutely neutral during the first years of the European conflict.

However, the Bells did not allow the distant hostilities to disturb their routine of long summers in Cape Breton and winters in Washington. One Sunday afternoon in Cape Breton in July 1917, Alec and Mabel decided to forget “our heavy burden of years, the war, and every other trouble,” as Mabel put it, and go for a walk. They were quite a sight: seventy-year-old Alec, his white hair long and uncombed, wore a swimsuit and a Japanese raincoat, while Mabel, aged fifty-nine, sported an old-fashioned ankle-length khaki skirt. But a stranger would quickly realize that this eccentric couple was very close. As usual, they held hands (although the observer wouldn’t know that this was so that Alec could spell words into Mabel’s hand). As usual, they often turned to face each other, so Mabel could read her husbands lips.

The Bells started off on the main road from the Point toward Baddeck. But Alec had never been satisfied with the beaten track, and he persuaded Mabel that they should plunge into the woods that covered the slope between the road and the shoreline. There was no path, and the Bells both ended up sliding down to the water’s edge on their behinds. Undaunted, they decided to remove their clothes and go for a swim, “the first time in a dozen years I have been in,” Mabel confided to Daisy, “and the water was simply delicious.” After their dip, they got dressed and walked along the rocky shore for a while, then struck back up the cliff. The going was so steep that they had to clamber up on all fours, grabbing at branches to haul themselves forward. By the time they reappeared at the Point, their clothes were filthy but their expressions were gleeful. “It was simply just such a tramp and scramble as Daddysan loves,” Mabel wrote, “but we haven’t had it together for a long time.” This was a couple for whom thirty-nine years of marriage had done nothing to diminish delight in each other’s company.

If there were two things that invigorated Alec, they were a bracing ramble and an embryonic invention. And by 1917, he was convinced he was about to present the world with a new and incredible invention—an innovation that would prove, forty years after the development of the telephone, that Alexander Graham Bell’s mind was as creative and original as ever.

Six years earlier, when the Bells and Baldwins had completed their round-the-world trip, Alec and Casey had returned to the challenge of designing their own species of hydrofoil vessels. Alec spent hours at the bench in the long laboratory building (situated between the boathouse and the cottage where Casey and his wife, Kathleen, now lived) overseeing the construction of tin models of hydrofoil hulls. Casey spent his time at the boathouse, fitting foils to existing hulls to see which style provided the most “lift” out of the water. Prototypes ranged from wooden foils of various sizes and shapes to a ladder-like arrangement of angled steel knife blades attached to the bottom of the hull.

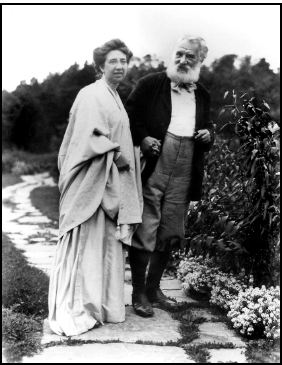

Alec and Mabel Bell in the garden at Beinn Bhreagh.

For a while, the experiments went well. Casey labored on, even when Alec was wintering in Washington or preoccupied with Montessori education or telephone celebrations. In 1911, a craft called the

HD-1

(for “hydrodrome,” as Alec persisted in calling it), powered by a fifty-horsepower engine, was ready for testing. It consisted of a rectangular twenty-six-foot-long body with short wings for balance and an aerial propeller at the stern, and it looked like a stubby seaplane. Alec and Mabel watched from the wharf as the propeller slowly drove the chunky construction out into the lake then picked up speed so that the vessel rose in the water on its foils. Once it was obvious that, this time, the craft was not going to fall apart, Alec hugged his wife and announced, “public attention will be riveted on Beinn Bhreagh.”

HD-i

was followed by

HD-2

(also known as

Jonah,

since at one point it was rescued from the deep) and

HD-3,

as Baldwin continued to refine the HD series design and increase the power of the motor. It looked, as Mabel told her daughter Elsie, “like [a] grasshopper, having [a] long slim body with four very long bent legs.” By 1913,

HD-3

had achieved speeds of fifty miles an hour. But Alec’s hydrofoil boats were still fragile constructions, staying afloat literally on a wing and a prayer.

HD-3

came to a spectacular end when it turned turtle in Baddeck Bay during a special demonstration for the prince of Monaco, whose yacht was moored nearby.

Alec’s spirits remained on the upswing, reaching toward the state of euphoria that success always induced. His mind raced with possibilities: he began to talk of building a houseboat with sails, and of propulsion by flapping wing devices. “I believe you can design a boat to beat the world record,” he told Casey, whom he had appointed manager of the estate and of the laboratory. He did add, perhaps in recognition of his own tendencies, “[o]therwise we may spend all our days in experiments and improvements and never reach the end.” He then encouraged Casey to start another project: a hydrofoil sailboat.

But in 1914, the trials ground to a complete halt: Great Britain declared war on Germany.

In common with most of their fellow North Americans, the Bells were shocked by events in Europe—the continent through which they had traveled so often. “We were all pursuing the even tenor of our lives when suddenly the news was flashed across the ocean,” Mabel noted. “It came like a knife cutting sharply and forever our present world from that of yesterday, and left us stunned, bewildered, utterly unable to conceive how this dreadful, this impossible event had happened.” As a citizen of the United States, Alec felt that he should remain neutral. So he reluctantly abandoned the hydrofoil vessel trials, feeling that, if successful, they could be used in war. However, during the winter of 1915 he couldn’t resist mentioning to Josephus Daniels, the U.S. secretary of the Navy, that

HD-3

had potential as a high-speed submarine chaser. But the secretary of the Navy showed no inclination to rush off in midwinter to a remote and snowbound corner of the British Empire to check out a boat that was unable to reverse direction, invented by an elderly eccentric with an Old Testament beard.

The Bells chafed to do something for the war effort without violating American neutrality. They experimented with drying dandelion leaves and other foodstuffs, in case of food shortages. (They tried rhubarb leaves “and found them very good,” Mabel told Daisy, “but Cousin Lily thinks they are not quite safe.”) Alec designed a candle-powered heater with which soldiers might dry their clothes in the trenches of France. Their most important initiative was to convert the Beinn Bhreagh laboratories into a boat-building plant, to produce lifeboats out of local timber. Mabel bemoaned the impact that this had on the headland: “[W]e are hewing down cherished trees, destroying the best-loved beauty spots on Beinn Bhreagh and erecting in their place huge ugly sheds just in the hope that we may be allowed to build ships for the U.S. government.” Nevertheless, in July 1917, an order from the British government for fourteen lifeboats was completed ahead of deadline, and Casey Baldwin delivered them to Sydney.

To celebrate, Alec organized a big dinner at the Point for the forty-four people who had worked on the boats. As a table centerpiece, Mabel had placed little silver paper models of the fourteen boats on mirrors edged with moss. That evening, she wrote to Daisy, “[t]hey sat down at 8.30 and got up somewhere about 11.30 and apparently are still at the piano led by Daddysan who is in high feather, looking his best Santa Claus in white waistcoat and velvet coat and very much alive. He stood talking with old time energy and vim [and] made a long speech on his favorite theme, the laboratory boat building and our fastest motor boat in the world.”

Alec’s spirits were high because, by the time the lifeboat order was completed, he was back on the hydrofoil warpath, in every sense. On April 6, 1917, the United States had finally declared war on Germany. In common with most of his scientist friends, Alexander Graham Bell had deplored American isolationism. The Bells had been appalled by the bloodshed, brutal conditions, and mounting casualties in France and by the German air raids on London. They shared the widespread outrage in the United States when a German torpedo sank the Cunard liner

Lusitania

off the coast of Ireland in May 1915, with the loss of over 1,000 lives, including those of 124 Americans. “We cannot allow American lives to be endangered in a species of warfare without precedent among civilized nations, and which is a distinct return to the most brutal practices of barbarism,” the

Baltimore Sun

had announced, in an editorial that captured the reaction of most of the Bell circle. But it took another two years—and the German decision to begin unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic—before President Wilson led the United States into war.

Alec’s regular Wednesday-evening soireé was in full swing when news of the president’s decision reached 1331 Connecticut Avenue. “The Graham Bell circle broke loose,” according to Dr. L. O. Howard, chief of the United States Bureau of Entomology and one of those present. “Few of [us] realized how heavy a burden of shame [we] were bearing…. [Various speakers] gave voice to … our enormous joy that at last our country had taken her place on the side of right and justice.”

Alec felt there was no time to lose if the hydrofoil was going to be part of the war effort, and he immediately headed for Baddeck. But five days after leaving Washington, he discovered he could not reach his destination. He had crossed the Strait of Canso and traveled as far as Grand Narrows, halfway up Bras d’Or Lake. But the thick ice on the lake had barely begun to break up, and the roads were unpassable. Casey Baldwin had managed to get down to Grand Narrows to meet his boss, and he watched the old man fume with frustration for three days. Finally, as Alec explained to Mabel, Casey had “a brilliant idea.” They would take the train along the eastern shore of St. Andrew’s Channel, as far as the little fishing village of Shunacadie, and then

row

the twelve miles across the lake to Beinn Bhreagh.

It probably sounded like a merry outing when Casey first aired his plan. In fact, the “brilliant idea” was madness. Soon after the two men set off, a wind sprang up and the water grew increasingly choppy. Alec had anticipated taking his turn at the oars, but Casey refused to contemplate the idea of his boss’s 250-pound bulk maneuvering around the little boat. “An upset was an uncomfortable thing to contemplate,” Alec admitted. If the boat tipped, there was no prospect of rescue, and they would never survive immersion in the freezing water. Large ice pans knocked against the rowboat, and powerful gusts of wind threatened to blow it too far south. By the time the two men reached the Beinn Bhreagh wharf, nearly five hours later, icicles clung to Alec’s beard, and Casey’s hands were blistered and raw. But it took only a brandy and hot supper at the Baldwins’ house to spur Alec on to planning a new vessel, the

HD-4,

which would be capable of speeds of over fifty miles an hour.

Alec was convinced that a hydrofoil boat could be of incalculable benefit in the Allies’ war effort. German U-boats were exacting a vicious toll on Allied shipping, and a hydrofoil, he argued, was the perfect vessel for coastal patrol duty. The minimal area of hydrofoil blades that would be submerged would render the vessel relatively safe in mined areas, and the air propellers would transmit no water vibration that might alert enemy shipping. The U.S. Navy Department was sufficiently intrigued to send two 350-horsepower Liberty motors.

The vessel that Casey and Alec designed that summer was huge. The

HD-4

had a wooden hull that was sixty feet long and shaped like a monster cigar. Outrigger floats projected like fins, one each side at the bow. These carried the engines, and slung on a steel tube that passed through the hull were the two main ladderlike sets of steel hydrofoils. In addition, there were two smaller sets of hydrofoils: one at the bow, to prevent any tendency to dive during liftoff, and one at the stern, to act as a rudder.

The war edged closer to North America. There were even rumors of German submarines in Bras d’Or Lake. On Thursday, December 6, 1917, several of the men working on the

HD-4

heard a huge explosion in the distance and speculated that the Germans had launched an attack nearby. In fact, the noise came not from enemy mortars but from the great Halifax explosion, 250 miles away, the largest man-made disaster in history up to that point. A French munitions ship laden with high explosives had collided with a Belgian relief ship as they navigated the narrow channel between Halifax harbor and Bedford Basin; over two thousand people were killed, and almost ten thousand injured. “I sent all our houseboat blankets to Halifax the very day of the disaster,” Mabel informed Bert Grosvenor. “We are told there is not a pane of glass left in Halifax.” Alec intensified his efforts on the

HD-4.