Reluctant Genius (57 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

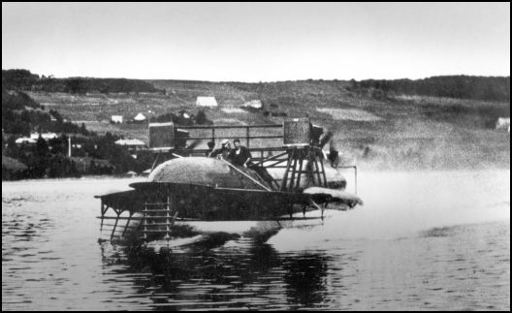

HD-4 roared down St. Andrew’s Channel in 1918.

In October of the following year, Alec, Mabel, and the laboratory staff watched anxiously as Casey Baldwin took the

HD-4

on its maiden voyage. The

HD-4

did not let them down. Once Casey had got the craft going at around twenty miles an hour, it lifted smoothly out of the water. Within seconds this monster vessel, weighing close to five and a half tons, was skittering across Bras d’Or Lake on about four square feet of submerged steel blades. The noise was deafening. “If you want to hear anything for the rest of the day,” declared the editor of

Motor Boat

magazine after joining Casey in the cockpit for a later trial, “stuff some cotton into your ears…. At fifteen knots you feel the machine rising bodily out of the water, and once up and clear of the drag she drives ahead with an acceleration that makes you grip your seat to keep from being left behind. The wind on your face is like the pressure of a giant hand and an occasional dash of fine spray stings like birdshot…. Baddeck, a mile away, comes at you with the speed of a railway train.”

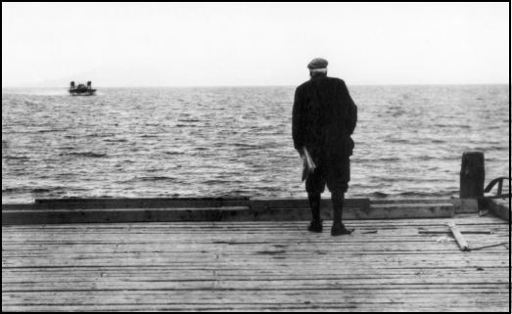

An anxious Alec watched Mabel speed across the water.

Alexander Graham Bell himself never rode in this, his latest creation, but his wife had always been more physically intrepid than he was. On November 11, 1919, Alec stood on the wharf, shoulders hunched and fists clenched, as Mabel (accompanied by Casey) went for a spin in

HD-4,

which achieved a speed of thirty-five miles an hour. Mabel was euphoric. “It was a most wonderful trip,” she wrote in her husband’s notebook. “She felt like a rock, so steady, and kept on an even keel…. Really the remarkable thing to me was the feeling of perfect confidence she inspired.” As Alec read this, did he notice that his wife had unconsciously described her own role in his life? Probably not, since he rarely explored his own feelings. He was simply overwhelmed with relief that nothing had gone wrong.

With the

HD-4

an unqualified design success, Mabel began to fret about patenting its unique features. She was bitter that Glenn Curtiss had recently made a killing from patents granted to the Aerial Experiment Association. Curtiss had purchased the AEA patents for a few thousand dollars when he formed his own aircraft company, but he had then sold all his patents, of which the AEA patents were by far the most valuable, to the U.S. government for a reported two million dollars. Curtiss, in Mabel’s view, had “been scheming to betray [his AEA partners] in such a way as to make it practically impossible for them to reap their fair share of their mutual benefits.” She insisted to her son-in-law David Fairchild that Curtiss owed “the equipping of his shop, the training of his men, and the doing of the experimental work … to Mr. Bell’s money, his brains, and the doings of his other associates.” Had her father, Gardiner Hubbard, been alive, he would never have allowed this to happen. Her husband would have achieved his burning ambition to secure another world-famous invention, and the names and fortunes of Casey Baldwin and Douglas McCurdy would have been made. But none of these three could plot a development strategy like the one that her father, a born promoter as well as a skillful patent attorney and knowledgeable entrepreneur, had devised for the telephone forty years earlier. She appealed to David to find somebody to help Alec and Casey now that they had something else to offer the world.

David Fairchild was unable to find such a person. And Alec had made a lifetime habit of ignoring these kinds of commercial issues. He had no interest in plunging back into patent litigation, especially as he watched Orville and Wilbur Wright conduct the same bitter battles as he had faced with the telephone. (The Wrights’ ruthless defense of their 1906 flying-machine patent is estimated to have cost them $150,000, or well over two million dollars in today’s terms.) He was far too busy lobbying both the British Admiralty and the U.S. government to take an interest in his new baby. In the summer of 1919, Baddeck pulsated with excitement. The village was full of newspaper men and newsreel photographers waiting for the roar of

HD-4

’s engines. Local residents proudly talked of “our Dr. Bell” as though he were Nova Scotia born and bred. Small boys hung around the Beinn Bhreagh wharf, staring at the strange craft and hoping to be invited to sit in the cockpit. It was a repeat of the scene at Hammondsport in the summer of 1907, when all those magnificent men in their flying machines had assembled at a disused racetrack to vie for the

Scientific American

trophy. On warm July mornings, the big brown boat would streak across the smooth bay, startling the seagulls into wheeling flight. The roar of its engines would cause everybody around the lakeshore to stop in their tracks and stare out at the torpedo-shaped vessel as it hurtled across the water. The white sails of schooners would flutter in its slipstream, yet it created so little wake that the sailboats would barely stir. To demonstrate its potential as a submarine chaser,

HD-4

carried more than three thousand pounds of extra load in dummy torpedoes, dropping them off one at a time to show that the maneuver would not upset its balance.

Best of all,

HD-4

achieved a speed of 70.86 miles per hour on one test run. This made it the fastest boat in the world. U.S. Navy observers reported that “at high speed, in rough water, the boat is superior to any type of high-speed motor boat or sea sled known.” Both Washington and London expressed interest in Alec’s hydrofoil work.

But once again, interest fizzled out. What was to blame? This time, it was not Cape Breton’s distance from political and financial centers that prevented businessmen and government officials from noticing what was going on there, as had been the case with tetrahedral cell construction. Nor was the problem Alec’s lifelong reluctance to hustle on behalf of his inventions. With the hydrofoil, it was timing. The American and British governments had just emerged from a devastating conflict that was already dubbed, with ghastly optimism, “the war to end all wars.” The market for new weapons of war had collapsed, and so had any public enthusiasm for spending on naval armaments. It was, wrote Mabel, “the death of all our hopes and high endeavors.” A “ship with wings,” as it was frequently described in newspapers, seemed more like a rich man’s toy in peacetime than a serious naval craft.

Alec and Mabel continued to hope that there might be a private market for the world’s fastest boat. Casey’s brother-in-law, a Toronto corporate lawyer named Colonel Jack Lash, helped Alec and Casey establish a company to protect their interests, and four patents were issued for original features of the hydrofoil. But Bell-Baldwin Hydrodromes Ltd. was a short-lived affair. In 1923, the company ceased operations and the shell of the amazing

HD-4

was left to rot on the rocky shore of Beinn Bhreagh.

Nevertheless, Alexander Graham Bell’s hydrofoil was an extraordinary invention, way ahead of its time. It kept its record as the fastest boat in the world for over a decade. And hydrofoil technology would be rediscovered half a century later.

By the end of the First World War, Alec had begun to show his age. There was no more floating in the lake at night with a lit cigar clamped between his teeth. His energies flagged, and Mabel became increasingly protective of the husband to whom she now wrote as “Darlingest Boysie.” In the summer of 1918, Helen Keller asked her great benefactor to appear in a motion picture of her life. Helen’s literary style was always lush, but on this occasion she went over the top:

If I had not had so many proofs of your love and forbearance, I should not dare even to consider making the request…. Dear Dr. Bell, it would be such a happiness to have you beside me in my picture travels! … Even before my teacher came, you held out a warm hand to me in the dark! … You have always shown a father’s joy in my successes and a father’s tenderness when things have not gone right…. You have poured the sweet waters of language into the deserts where the ear hears not, and you have given might to man’s thought, so that on the audacious wings of sound it pours over land and sea at his bidding. Will you not let the thousands who know your name and have given you their hearts look upon your face and be glad?

Helen’s letter “would move a heart of stone and it has touched me deeply,” replied Alec. Although he had the “greatest aversion to appear in a moving picture,” he promised to travel down to Boston or Washington if required by the filmmakers. To Helen he wrote, “I can only say that anything you want me to do I will do for your sake.” But a few days later, Helen received a further missive from Beinn Bhreagh, this time from Mabel. “Helen dear,” she wrote, “my husband is no longer a young man. At any time such a journey … would be a great tax on his strength, but just now, in midsummer, the risk would be greater than I am willing he should take.” Unlike her husband, Mabel was prepared to say no. “He is dreadfully sorry to refuse any request of yours, and so am I, but I know you will realize how much his life and health mean to me, and that I cannot let him take what I know is a real risk to both.”

Alec’s health had always been a concern. There were the early brushes with tuberculosis, his abnormal sensitivity to light, severe headaches, frequent insomnia, and breathlessness. Ever since his marriage, Alec had always been a hearty eater, and he was seriously overweight. An exasperated Mabel complained to Daisy in 1914, “Discovered depths of iniquity and deceit in my husband undreamt of during 36 years of marriage. He complains of indigestion. We are all in despair, worried to death over chicken curry. Husband absolutely quiet about surreptitious lunch on ham and bad eggs! Guilt detected by egg spots on waistcoat!”

Moreover, Alec had been diagnosed with diabetes in 1915. The incurable and (before the discovery of insulin) untreatable disease was starting to take its toll. Mabel tried even harder during these years to cut extra calories from her husband’s diet. She told Charles to take Alec a lighter cereal for his breakfast. But within minutes of Alec’s noticing his breakfast tray, Charles was summoned. “I see you’ve brought me a dish of shavings for my breakfast,” an indignant Alec protested. “Are you playing a prank on me?”

Charles replied, “That is not shavings, sir, it is corn flakes, a new breakfast food.” Alec would have none of it. “Then flake it away and bring me my oatmeal and brown sugar,” he growled. “Whoever heard of oatmeal hurting a Scotchman?”

For all his bravado, however, Alec felt time pressing on him. He focused his waning energies on his hydrofoils and let other Beinn Bhreagh projects fade away. He decided it was time to get rid of his sheep. “The constant labor of the records was becoming burdensome,” according to Alec’s secretary, Catherine Mackenzie, “and there were other things to which he wanted to give his energies.” Alec was delighted to see his coachman, John McDermid, bidding on some ewes and rams at the auction—he had had no idea that McDermid had an interest in animal husbandry. His delight evaporated when he walked into the sheep barn the following morning and was greeted with a chorus of “baas.” Mabel had commissioned McDermid to bid for her at the auction, because she did not want to say goodbye to the sheep. Alec exploded with wrath, telling everyone in earshot, “I thought I was

through

with those damn sheep!” But he swallowed his exasperation because he didn’t want to hurt his wife’s feelings. “I can see him now,” Catherine wrote, “patting Mrs. Bell’s hand affectionately and dictating a pleased account of it for ’Home Notes.’”

And yet Alec’s fertile brain was as active as ever. He continued to stay abreast of events beyond the Beinn Bhreagh workshops. Although he felt no particular loyalty to any political party, he had become an ardent supporter of Woodrow Wilson after hearing him speak at a dinner in Philadelphia in 1912. He followed avidly the debates at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, and those on the establishment of League of Nations. Catherine Mackenzie would turn to the report in the

New York Times

while her boss “would pull up the rug around his knees, lay down his glasses, light up his pipe and shout, ‘Now! Let’s have it, in your best oratorical manner, my dear!’… I would declaim the whole speech [with] Mr. Bell shouting, ‘Hear! Hear!’ ‘Yaw! Yaw!’ and ‘Applause’ at intervals.” The afternoon would wear on, the fire in the big woodstove in the laboratory office would die down, the pile of letters would remain untouched, and Alec would comfort himself that, thanks to his political hero, the world might achieve a permanent peace.