Reluctant Genius (51 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Alec was convinced that experiments with an airborne structure made of tetrahedral cells might move the science of flight along, because they might yield valuable information about aerodynamic stability. And he now had an additional assistant. Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, a twenty-five-year-old graduate of West Point, was an aviation enthusiast who had introduced himself to Alec in Washington and wangled an invitation to Cape Breton to see the kites. Mabel was charmed by this tall, soft-spoken Californian who always held the door open for her, helped her carry parcels, and quickly learned to speak directly to her so she could read his lips. At her urging, in September 1907 Alec persuaded the U.S. Army to dispatch Lieutenant Selfridge to Beinn Bhreagh as an observer. As Robert V. Bruce describes in

Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude,

“the lieutenant and the two engineers introduced a new precision to Bell’s meticulously recorded but poetically calibrated measurements. Now wind velocity was read from an anemometer, not the look of the waves; altitude from a clinometer rather than the snapping of a manila rope or the pulling loose of a nailed cleat.”

At this stage, the Bell team was still trying to develop a powered kite, and for this they needed a lightweight engine. Alec ordered one from G. H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company in Hammondsport, a small town fifty miles south of Rochester in northern New York State; the company had already provided motors for several makers of dirigible balloons. Alec had met Curtiss in January 1906 at the New York City Auto Show, at which aviation pioneers had also been invited to participate. The Wrights had treated the show with their customary suspicion, telling the organizing committee that they would display only the crankshaft and flywheel of their 1903 engine, because “[i]t would interfere with our plans if we should make public at once a description of our machine and methods.” Alec had not only exhibited a large tetrahedral kite but had also taken a great interest in other exhibitors, especially Curtiss’s engines. He started referring to the young engine-builder as “the greatest motor expert in the country,” and when the Beinn Bhreagh group decided it needed an engine, Curtiss was the obvious source. But first Glenn Curtiss took a long time to fill the order, and then the model he supplied proved unsatisfactory. Alec ordered a larger one and offered Mr. Curtiss twenty-five dollars a day to deliver and demonstrate it in person.

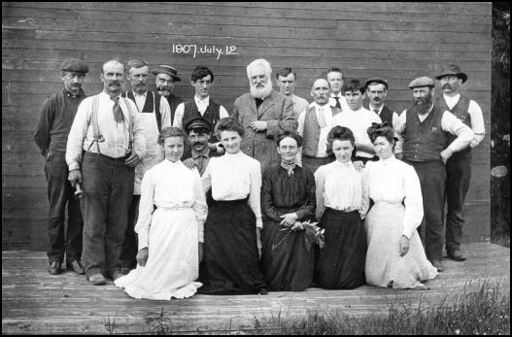

As Alec’s obsession with manned flight grew, his Baddeck workforce expanded.

When Glenn Curtiss arrived in Cape Breton, he struck Alec and his young colleagues as a rather glum young man who rarely joined the college-boy pranks enjoyed by the others. But Casey, Douglas, and Tom had to admire the twenty-nine-year-olds technical skills. Curtiss had started a bicycle shop from scratch and then had begun building motorcycles. He was creative and ingenious (tomato cans had served as both carburetor and gas tank on his first makeshift engine), and in 1903 he had won the U.S. national motorcycle championship. A few weeks before he traveled to Canada, he had broken the world record for speed, averaging 136 miles an hour on his motorcycle over the course of a mile. And although he was a fish out of water in rural Cape Breton, Curtiss was intrigued by the Bell setup and by the Grand Old Man’s ambitions. He also felt a special bond with his deaf hostess: since his own sister Rutha had lost her hearing to meningitis as a child, he was used to enunciating his words clearly so his lips could be read. He decided to stay. He was the fourth and final member of the team.

Alec now had four enthusiasts at his side. He “enjoys his boys immensely,” Mabel told her mother, “and they all seem pleased with him.” After dinner each evening, once Mabel had retired to bed, “the four make straight tracks for Alec’s study.” While their benevolent patron puffed away at his pipe, the young men sketched out plans for flying machines. Alec listened carefully, pointing out different ways of coming at a problem or suggesting refinements to their ideas. After the younger men had gone to bed, Alec would “put on his dressing gown,” according to Charles Thompson, and “get his note-book and pen and settle down to work.” He would still be working when Charles bought him coffee at 6 a.m., but then he would retire, leaving his notebook open on his table. While their patron slept, the younger men would translate his drawings, sketches, and notes into prototypes and experiments.

This was just the kind of collaboration that Mabel had wanted for Alec: a group who would provide the structure, drive, and skills to keep his experiments and spirits on the rails. The creative atmosphere that now suffused Beinn Bhreagh was, in the words of Seth Shulman, biographer of Glenn Curtiss, a cross between “the rigors of a fast-track engineering laboratory and the playful pleasures of a child’s summer camp.” That September, after an afternoon of messing about with boats and kites, Alec and his four protégés returned to the Point to dry themselves in front of the fireplace. Mabel poured them all tea, handed around buttered toast, and made her proposal.

She had recently received $20,000 ($415,000 in today’s currency) from the sale of a piece of property in Washington that she had inherited from her father, she announced. She wanted to put the group on a formal, legal footing by underwriting their expenses, construction materials, and salaries. Douglas McCurdy and Casey Baldwin would each receive a salary of $1,000 a year. Curtiss, already an established businessman, would receive $5,000 a year while in Cape Breton and half that amount when away. Tom Selfridge would not receive a salary since he was already on full pay as an army officer; Alec would serve as chairman without salary. “My special function, I think,” Bell decreed, “is the co-ordination of the whole—the appreciation of the importance of steps of progress—and the encouragement of efforts in what seem to me to be advancing directions.”

The Bells and the four young men traveled to Halifax to sign the Aerial Experiment Association agreement on October 1, 1907, in front of a notary and the U.S. consul general. The AEA had a life expectancy of at least one year, and a goal (as Tom Selfridge put it) of getting “into the air.” Bell’s boys took up residence at the Point. “I have a perfect forest of them, 30 feet of Americans and about fifteen of Canadian,” Mabel told her mother. She loved the vigor and gusto of the young men. They had transformed her and Alec’s life at Beinn Bhreagh from that of an aging and now childless couple exchanging desultory comments on the day each evening into a lively extended family eagerly planning their next adventure. Her guests were “as nice as they can possibly be and a hundred times less trouble than girls to entertain.” And for Alec, this was one of the happiest periods in his life, as he and his new colleagues lived and breathed aviation.

The AEA’s first manned craft was a huge tetrahedral kite, composed of 3,400 pyramidal cells, each covered in hand-sewn bright red silk. Alec had named this extraordinary creation, which looked like a giant slab of scarlet honeycomb, the

Cygnet.

“Friday, Dec. 6, 1907,” wrote Alec, “is a day ever to be remembered.” This was the day that Tom Selfridge crawled into a small space in the center of the

Cygnet.

The kite was then placed on a small boat, and the

Blue Hill

(a local steamer that had a regular run between Baddeck and Grand Rapids) towed the whole assemblage out of Baddeck Bay. Tom “lay on his face on the ladder floor provided,” recalled Alec, “covered up with rugs to keep him warm for he was lightly clad in oilskins and long, woollen overstockings without boots.” Once the

Blue Hill

had steamed well out into the chilly, wind-whipped waters of Bras d’Or Lake, the men on the

Cygnef’s

launch boat cut the ropes that held the kite down and gave the signal to the

Blue Hill

to go full steam ahead. Alec, Mabel, Douglas, and Casey all held their breath as they watched the

Cygnet

give a slight tremor, then rise gracefully at the end of its towline and fly steadily about 150 feet above the lake, where it hovered for seven minutes until the wind dropped. The spectators cheered like mad, but Selfridge was now in difficulties. His forward vision was obscured by red silk, and the kite’s descent was so slow that he did not realize he should cut the towline until he was already in the water. After alighting gently and safely upon the water, Lieut. Selfridge found the kite being towed through the water at the full speed of the steamer

Blue Hill.

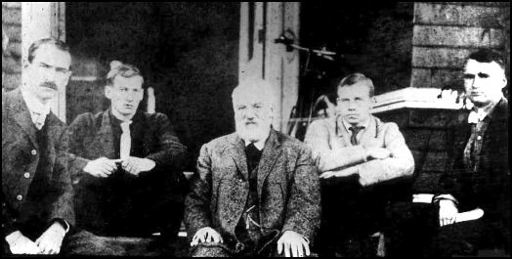

The Aerial Experiment Association: (left to right) Glenn Curtiss, Douglas McCurdy, Alec Bell, Casey Baldwin, and Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge.

The spectators were terrified. Where was Tom? They couldn’t see him in the tangle of ropes and spars, and they knew that nobody could survive long in the icy water. If he had been knocked unconscious, he would drown.

Within minutes, though, Tom appeared—he had managed to swim clear of the fragile contraption. But the

Cygnet

was dragged to pieces. The next day, little girls from Baddeck ran along the lakeshore gathering up the red silk remnants of the tetrahedral cells from which to make dolls’ dresses.

Alec’s immediate reaction was that the kite’s destruction was a “catastrophe.” Yet he proved unusually resilient on this occasion— within a few days, Mabel told her mother that he was “jolly again.” He felt vindicated: his kite experiment had not resulted in any injury to the pilot, and the

Cygnet

had proved, in Alec’s words, that “the tetrahedral system can be utilized in structures intended for aerial locomotion.” The kite had proven itself incredibly stable in the gusts of wind over the lake. With a bit more research, he speculated, he might be able to construct a kite so that a man could climb up a rope ladder, start the motor, and fly off to Halifax. (Tom Selfridge, however, challenged Alec’s calculations by pointing out that the

Cygnet

was seriously overbuilt: only 41 percent of the tetrahedral cells contributed any lift.)

At the same time, the Aerial Experiment Association was performing just as Mabel had hoped: Alec’s young colleagues were keeping him abreast of scientific developments elsewhere. Bell’s Boys, as they were widely nicknamed, now took their boss in a different direction. They convinced Alec that it was time to look at issues of control in the air, as well as stability. This meant moving on to manned gliders and, for the sake of milder winter weather, shifting the AEA’s seat of operations to Hammondsport, where Glenn Curtiss had his machine shop and where prototype biplanes could take off from the frozen surface of Lake Keuka. By January 1908, the young men were hard at work on a rigid biplane design similar to an early Wright model. Alec had too many commitments in Washington to let him join his boys, so he and Mabel remained in Washington, four hundred miles away. He was kept up to date on their work through a weekly newsletter with the splendidly important title the

AEA Bulletin.

The AEA members agreed that each of the five of them should design his own aircraft but would be on call to help any of the others. The group’s major achievements, however, all came from the younger men. Tom Selfridge was first out of the gate, with

Red Wing,

a biplane named for the red silk that covered its wings—the same red silk that they had used on the Beinn Bhreagh kites. “It is a beautiful machine,” Alec, who could keep away no longer, reported to Mabel in March. Its propeller, mounted at the rear, was powered by a forty-horsepower Curtiss engine, and the pilot had two controls: an elevating device at the front and a rudder at the rear, for direction. On March 12, Tom was absent, so Casey was the pilot as Douglas and Glenn pushed it out onto the frozen lake. Its forty-three-foot span of scarlet wings glowed against the blue winter sky and the brilliant white ice. On its first flight, in front of a crowd of excited spectators, the little plane managed to climb for 10 feet and fly 319 feet in a straight line (the rudder’s only purpose seems to have been to prevent it from veering to right or left). Since the Wright brothers had done almost nothing to publicize their test flights, this was the first public demonstration of a powered, manned flying machine in North America. Casey had become the first British subject and the seventh human being to fly. Unfortunately, on its next flight, a gust of wind from the wrong direction caught the

Red Wing

and it tipped sideways and crashed into the ground. Casey walked away.