Reluctant Genius (50 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Mabel (left) encouraged her husband to patent the tetrahedral cell system of construction.

In mid-November, an Atlantic gale came shrieking up the Bras d’Or, whipping the water into mountainous waves and tearing the sloops in Baddeck harbor from their moorings. This was what Alec had been waiting for. Early the following morning, Mabel watched her husband roar out of the house with excitement and stride toward the newly built kite house with the vigor of a man half his age. But the Baddeck workmen had looked at the raging bay and decided not to row across a mile of choppy water to Beinn Bhreagh that day.

Alec was devastated by what he regarded as his employees’ treachery. Perhaps his father’s death had affected his emotional stability after all, although he had appeared to survive it without a problem. Mabel watched her husband slowly walk back to the Point, his shoulders slumped in dejection as he muttered “Sheesh, sheesh” between clenched teeth. “The shock was terrible for Father,” she told her son-in-law Bert. “He looked gray when he came home, wrote a short note dismissing the staff and closing the laboratory, turned his face to the wall and never spoke again that day or night.”

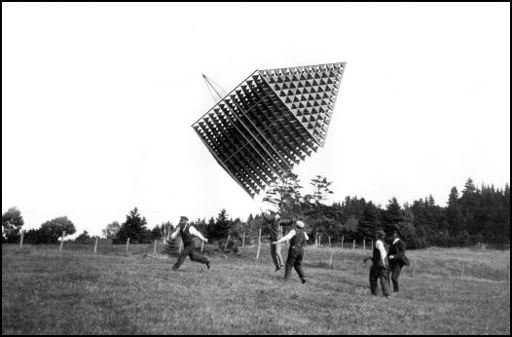

Mabel sat in her study for a few hours, watching the whitecaps on the lake water and remembering all the times in their marriage when Alec had overreacted to setbacks or plunged into despair. Then, as evening approached, she took matters in hand. “While he slept,” she admitted to Elsie, “I called for volunteers as I knew he would never ask himself.” The following morning, as the gale continued to blow, she rounded up all the men on the estate—Charles Thompson, Arthur McCurdy, the shepherd, and various boys hired to help with the garden. Mabel roused Alec, and the small party made its way down to the kite house. Braving a wind that whipped the caps off their heads and brought tears to their eyes, they lugged the giant kite up to the kite field and maneuvered it into position. The red silk in each tetrahedral cell bellied out, and as a particularly strong gust tore across the headland, the kite rose. While the men hung on to the guide ropes with all their might, the inventor almost took wing himself with glee. “The experiment was so satisfactory,” reported Mabel, “that it demonstrates that this form of kite could sustain a much greater weight than he had dared hope.”

As usual, success sent Alec’s spirits soaring again. He quickly hired back all his Baddeck workmen and sketched for them a new design: a kite composed of 1,300 cells, providing 440 square feet of lifting surface, packed together into a wedge shape. He named his enormous new creation

Frost King,

because Arthur McCurdy’s daughter Susie had recently married a man called Jack Frost. Within a month,

Frost King

was not only airborne but also had proved one of its inventor’s key hypotheses: that a kite could have sufficient lift to bear the weight of a man. Neil McDermid, brother of the Bells’ coachman, forgot to let go of the tether rope he was holding and was wafted thirty feet into the air. The kite’s designer was torn between euphoria and fear—euphoria that

Frost King

supported McDermid’s weight, and fear that McDermid might let go of the rope and be killed. Alec did, however, have the presence of mind to capture the moment on film. Once McDermid was safely back on terra firma, Alec rushed back to the Point and burst into his wife’s study, waving the Kodak camera.

when the enormous Frost King caught the wind, it appeared to vindicate Alec's faith in kites.

“Develop, develop,” Alec shouted at his startled wife. “We’ve got him!” Mabel took the film down to her basement darkroom and developed the film “slowly and calmly,” as she informed Bert, “in spite of Mr. Bell popping in and out the door, jumping about like a boy.”

“Mr. Bell is so happy and so excited underneath a very quiet demeanor—it means so terribly much to him,” Mabel confided in Bert Grosvenor. “We’ve just lived for this moment.” She hadn’t seen Alec so elated since he had invented the photophone in 1880, while she was pregnant with Daisy; his sense of accomplishment infected the whole household. For over twenty years, until the patent for tetrahedral cells had been issued, Alec had been unsettled and struggling—flinging “seaweed on the sand,” as she had put it to Daisy, then retreating “to fling more seaweed in some other wildly separated place.” Now he had an invention that he could concentrate on.

At the same time, Mabel had watched him enjoy a new experience: the company of his sons-in-law. “He and Bert went off yesterday … in Bert’s boat,” she told her mother in 1904. “They were in such good spirits and pleased with each other. I can’t remember Alec’s being so much interested in a spree before for years.” The sight of her husband bonding with men young enough to be his sons triggered wistful thoughts in Mabel of the might-have-beens of their marriage—if only those two little baby boys had lived. But Mabel was never one to dwell on lost opportunities. She decided to act on her own suggestion of years past and bring in some competent men to help her husband and fill the space those long-lost sons might have occupied. “You want heirs to your ideas,” she told her husband firmly. She began to put together a team that would, within a few years, have a significant impact on the development of flying machines.

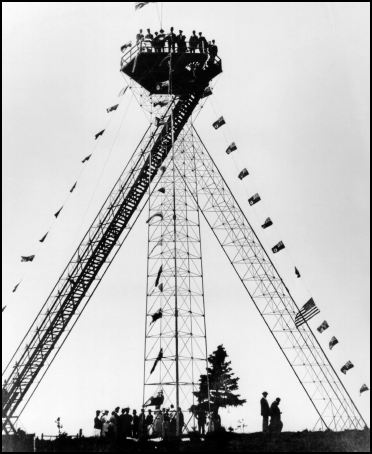

The first young man Mabel recruited to help her husband was a Baddeck native: Douglas McCurdy, son of Alec’s longtime secretary Arthur McCurdy. Douglas was a dark-haired, long-limbed, bright fellow who had enrolled as an engineering student at the University of Toronto. Since childhood he had been like an adoptive son to the Bells, and now he spent his summers back in Baddeck, often helping on the Beinn Bhreagh estate. In 1906, Mabel wrote to him and asked him to see if he could recruit any of his fellow engineering students to come to Baddeck and help Alec with tetrahedral constructions. Mabel knew that her husband needed the assistance of someone who was on top of the advances in mechanical and electrical engineering in recent years. Alec could operate brilliantly on intuition—his notebook shows a sketch of a trestle bridge constructed of tetrahedral forms, with a train chuffing over it, a scribble of smoke rising from the engine—but he always needed a skilled craftsman for scale drawings, models, and execution. Who would be his new Tom Watson? In particular, which of Douglas’s friends was trained in the kind of calculations required for a construction that Alec had had in mind for some years: a tower on Beinn Bhreagh’s highest point? Mabel was eager to see the tower built, to demonstrate the potential of tetrahedral construction.

Douglas talked to a Toronto crony, Frederick Baldwin—known to all his friends, on the strength of his baseball abilities, as “Casey,” after the poem “Casey at the Bat.” The grandson of Robert Baldwin, a famous statesman in pre-Confederation Canada, Casey combined the easy congeniality of an upper-crust Torontonian with a sportsman’s enthusiasm for outdoor life. He arrived in Baddeck in the summer of 1906 for a two-week visit, met the famous Alexander Graham Bell, and promised to come back in the fall. On his return, he began hammering out of half-inch iron pipe the four-foot tetrahedral cells from which the tower would be assembled. Mabel wrote to Daisy, “Mr. Baldwin begins tomorrow on the construction of a steel tetrahedral tower. He expects to get the whole thing up with just a jackscrew instead of the expensive and complicated machinery usually necessary, so perfectly are the cells fitted one into another.”

Flags waved when the tetrahedral tower was opened in August 1907.

By November that year, construction of the huge tower, looking like a giant camera tripod with its three seventy-two-foot legs, was well underway. Mabel’s spirits rose alongside the construction: as she confided to her mother, “It is such a lovely thing to see my husband at last, before it is too late, working in company with a capable young man who so thoroughly believes in him and his latest invention that he is staking his whole future on it.” The following August, Alec organized an elaborate opening ceremony for the tower, with bunting, speeches, and a commemorative article in the

National Geographic Magazine.

Tetrahedral cell construction had obvious advantages: Buckminster Fullers patented octet truss uses a similar concept, and some large geodesic domes are reinforced with struts that form tetrahedrons. But Alec’s invention received no attention in 1907 because no structural engineers were ready to make the three-day journey to check out this amazing tower in the backwoods of Cape Breton. In any case, Alec’s mind was on flying machines, not three-legged towers. He had just learned that aviation science had taken a great leap forward—and he wanted to be part of it.

Chapter 19

B

ELL’S

B

OYS

1906-1909

O

n December 17, 1903, a young bicycle mechanic called Wilbur Wright had made the first-ever flight in a powered biplane, named the

Flyer,

at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The plane had been built by Wilbur and his younger brother, Orville, who together ran a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio.

Like Alexander Graham Bell, these two young men, sons of a bishop in the Church of the United Brethren, had followed with keen interest the exploits of pioneer aviators such as Otto Lilienthal and Samuel Langley. In 1899, they had written to the Smithsonian Institution requesting everything available on aerodynamics, gliders, and planes, and then they had started building gliders in their bicycle shop. But to fly their gliders, they needed big winds. The U.S. Weather Bureau recommended to them Kitty Hawk, a long sandy beach on the one-hundred-mile Outer Banks of North Carolina, and one of the windiest stretches of ground in the country. It was ideal for the grimly brilliant Wrights, since only a handful of people lived there and the brothers were obsessed with secrecy. At Kitty Hawk, from 1900 onward, the brothers graduated from unmanned gliders to manned gliders to powered, manned biplanes. Through painstakingly methodical research, they managed to develop what had eluded their competitors in the race to the skies: a system of flight control for their creations. While other aviation pioneers, including Langley and Alec Bell, directed all their attention to getting a machine into the air, Orville and Wilbur Wright had worked out how to control the movements—the pitch, roll, and yaw—of a flying machine once it was airborne.

Although the

Flyer’s

successful flight took place only six days after Langley’s aerodrome made its disastrous plunge into the Potomac, the Wrights were not keen to publicize their achievement. They wanted to patent their innovations before rivals could steal them, so they refused to release photographs of the

Flyer

and they discouraged reporters. When their first attempts to fly an airplane in a cow pasture outside Dayton failed, newspapers lost interest. There were so very many avid aviators claiming supremacy in the air for their colorful assortment of balloons, dirigibles, and heavier-than-air flying machines—who knew which ones had really made a breakthrough?

However, in 1906, Alec had held one of his Wednesday-evening get-togethers of scientists in Washington. Among those present was Octave Chanute, an elderly civil engineer who had published a volume entitled

Progress in Flying Machines

in New York in 1894 and who had been a mentor to the Wrights. With great aplomb, Chanute stuck his thumbs in his vest pockets and stood up to announce that the Wrights had built a flying machine that really flew. According to David Fairchild, who was attending the distinguished gathering in his new status as the host’s son-in-law, Alexander Graham Bell asked, “What evidence have we, Professor Chanute, that the Wrights have flown?” Chanute, who had visited the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk and loved the drama of this moment, paused until he had everybody’s attention. Then, with great solemnity, he replied, “I have seen them do it.”

Alec could hardly wait to get back to Beinn Bhreagh and share the news with Douglas and Casey. When he discovered an account of the Wright brothers’ flying machine in the French journal

L’Aérophile,

he expressed his exasperation to Mabel: “It seems strange that our enterprising American newspapers have failed to keep track of the experiments in Dayton, Ohio, for the machine is so large that it must be visible over a considerable extent of country.… This seems to be due to the desire for secrecy.”