Reluctant Genius (49 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Daisy herself was another reason why, during these years, Alec had great difficulty in devoting himself to the workbench. In the spring of 1904, she announced that she wanted to explore her interest in art rather than become a Washington debutante like Elsie. She and a friend took an apartment in New York and began attending drawing lessons in the studio of Gutzon Borglum, an American sculptor who had studied in Paris with Auguste Rodin. Mabel was sympathetic to her daughter’s aspirations but shocked by the raffish mores of New York’s art world. Alec was no help: it was already lambing season in Cape Breton, and he had fled society life to pursue his sheep-breeding experiments and fly his huge kites at Beinn Bhreagh. Mabel felt ill equipped to venture alone into the art-student scene. After years of taking most of the responsibility for their daughters’ upbringing, Mabel felt that headstrong Daisy’s bohemian ambitions were more than she could handle. She wrote to Alec outlining Daisy’s plans, which she knew would startle him.

Whatever Daisy’s spoken reasons for her dive into New York, her unspoken motivation was clear: she wanted to catch her father’s notice. And she more than succeeded. Alec was so shocked that he downed his tools in his laboratory. “I do not approve of this at all,” he announced. He complained that Daisy had not consulted him about her new direction. He worried that Borglum “is a man I never heard of before, and of whose moral character I know nothing.” He insisted on making a special trip to New York to “call upon Mr. Borglum and satisfy myself concerning him.” Gutzon Borglum had a way with wealthy men, whom he cultivated assiduously as patrons. He had recently completed a sculpture of the apostles for New York’s St. John the Divine Cathedral, and would later be commissioned to carve the monumental sculptures of presidents George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Thomas Jefferson into Mount Rushmore, in South Dakota. He seems to have worked his magic on Alec. Alec left New York reassured that his daughter was in safe hands: his “darling Daisums” was allowed to stay.

One day, however, Daisy airily mentioned to her mother that she had accompanied her friend Alice Hill on a visit to a gentleman’s boardinghouse. Such behavior was simply “not on” for the daughters of America’s ruling class. Visions of her daughter getting a reputation as fast and loose gripped Mabel. “I cannot see any need of your breaking the conventions so far in order to have a good time,” she scolded Daisy. “I am liberal enough and broadminded enough to go against every convention in the land, if enough is to be gained by doing so, but I cannot see that you are gaining enough to warrant running counter to your mother’s and fathers feelings of propriety…. [I]t is not customary for young ladies to go to a gentleman’s boarding house and club and I do not like you doing it.” Mabel knew that if Alec heard about this, he would hit the roof. This time, Mabel swallowed hard and dealt with the situation by herself: “I have not said anything to Papa about this or shown him your letters.”

Mabel needn’t have worried. In November 1904, Daisy’s brother-in-law, Gilbert, introduced her to a distinguished botanist, David Grandison Fairchild, who had recently lectured to the National Geographic Society. A tall, thin thirty-four-year-old with sandy hair, a pale mustache, and a pair of dark-rimmed pince-nez, David worked for the U.S. Agriculture Department and had just returned from Baghdad for the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction. He was far more interested in plants than paints. But the affable, adventurous scientist was dazzled by this self-assured young woman eleven years his junior, who drove through the Washington countryside in her own electric automobile “at incredible speed, twelve miles an hour.” And for all her bohemian escapades, at heart Daisy was as conventional as her parents. Romance quickly developed, and David and Daisy were married in April 1905. Both Bell girls had met their husbands through the aegis of the National Geographic Society. Mabel had been right to bemoan Alec’s detachment from his daughters’ prospects: it was thanks to the society founded by her father rather than to the fame of her husband that her daughters had found suitable partners within Washington’s status-conscious society.

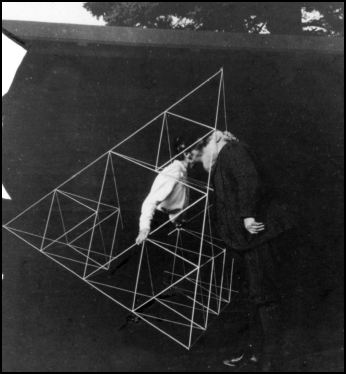

Alec’s mind, as usual, was on other things—specifically, on tetrahedral cells, the four-sided cells in which each side is an equilateral triangle. He could see that tetrahedral construction might have all kinds of applications in engineering projects, owing to its three-dimensional strength. As he wrote in an article for the

National Geographic Magazine

in 1903, the tetrahedral cell combined the qualities of strength and lightness: “Just as we can build houses of all kinds out of bricks, so we can build structures of all sorts out of tetrahedral frames…. I have already built a [sheep] house, a framework for a giant wind-break, three or four boats, as well as several forms of kites, out of these elements.” Mabel had even persuaded him to complete all the paperwork required to patent his work, which she was convinced had potential for railroad-bridge trusses. (?Alec would never have done anything more than talk about it, I am pretty sure,” she wrote later.) On September 20, 1904, Patent No. 770,626, for “aerial vehicle or other structure,” was granted to Alexander Graham Bell— the first patent he had received since 1886, when he and his associates patented the graphophone, an early form of phonograph. He was also granted a joint patent with his Baddeck assistant Hector P. McNeil for a tetrahedral connector.

It was the potential of tetrahedral cells in kite construction that intrigued Alec. He had started making tetrahedral cells, each side measuring ten inches, out of aluminum tubing rather than the black spruce of his earlier experiments. Teams of girls from Baddeck were hired to sew red silk onto two of the four triangular faces of each cell. Alec had selected silk because it was light and strong; he preferred the color red because it offered more contrast in the black-and-white photographs that he or his assistant Arthur McCurdy now took of all his experiments.

Kites appealed to Alec because they were inherently safer and more stable than biplanes and presented less risk to their pilots in test flights. He was consumed with the challenge of building the biggest kite he could—a kite that, eventually, might both carry a man and be powered by an engine. He watched his friend Dr. Langley come to terrible grief in December 1903 with his first two attempts at manned biplanes, powered by gasoline engines. The first of Langley s manned aerodromes, launched from the houseboat on the Potomac River, plunged into the river like “a handful of mortar,” according to the

New York Sun.

The reporters present, who had always found Langley arrogant and rude, guffawed. The second biplane (nicknamed “Buzzard” by the press) collapsed in midair. Langley’s chief engineer and designated pilot, Charles Manly, scrambled to safety, but the newspapers had a field day mocking the director of the Smithsonian Institution. Langley himself never recovered. Alec believed that the ridicule “broke his heart” and contributed to his death from a series of strokes only three years later.

But Alec was swimming against the tide by concentrating on kites rather than on winged planes. Many of Alec’s friends thought his obsession with kites was leading him up a blind alley. His former patron Sir William Thomson, who had been so enthusiastic about the telephone at the 1876 Philadelphia Exhibition and who had become Lord Kelvin in 1892, expressed extreme skepticism. Now elderly but still a highly respected physicist, Kelvin met Alec in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1897 and suggested to him that he was “wasting his valuable time and resources.” In 1901, Alec’s protégée Helen Keller visited the Bells in Cape Breton. She had a fine time holding the guide ropes on one of her mentor’s constructions and feeling the powerful tug of the airborne contraption. Nonetheless, she privately told a friend, “Mr. Bell has nothing but kites and flying machines on his tongue’s end. Poor dear man, how I wish he would stop wearing himself out in this unprofitable way.”

“The word ’Kite’ unfortunately is suggestive to most minds of a toy,” admitted Alec, “just as the telephone at first was thought to be a toy.” But he had no time for any doubting Thomas who didn’t realize that

his

kites were “enormous flying structures.” “Keep on fighting” had now become Alec’s motto, and his kites just grew and grew in size. In 1904, he built a kite with a single wingspan composed of dozens of tetrahedral cells, plus a short horizontal tail. “We have everything ready for experiment with the big kite,” he told Mabel. “So we are whistling for wind—not too much, and not too little, and not in the wrong direction.” That kite took wing and looked so like a great soaring bird that he named it the

Oionos

—the Greek word for a bird of omen.

That summer, Melville Bell came to Beinn Bhreagh for what would be a last visit. He had not slowed down after the death of Eliza Bell in 1897: he had always had an eye for a pretty girl, and he soon remarried. His bride was a fifty-four-year-old Canadian widow named Harriet Shipley— “as sweet and good as she can be,” according to Alec, who also noticed his father “stepping out briskly like a young man.” But as Melville entered his eighties, his health began to fail. He now tried to arrange his life so that he was always close to his son, in either Cape Breton or Washington. Mabel told her mother that her father-in-law’s first question in the morning, “constantly repeated throughout the day, [is] ’Where is Alec? Is he well? When will he come?’ And Alec reads to him for hours every evening, or he likes to listen to Alec playing and singing.”

In November 1904, Alec wrote to Mabel, who had already returned to Washington to be with her mother:

I am much troubled by my fathers weakness. He is not in a condition to stand a long journey to Washington at the present time, and I am perplexed to know what to do. He seems to be happy here, but hardly says a word. He likes to have me sit beside him and looks forward

pathetically

to the evening, when he knows I will give him all my time. .. . Although claiming to be perfectly well, his physical weakness is so great, and his somnolency, as to make me fear that he may not be long with us. It is a great comfort to me to be able to be with him now, and a great happiness that he wants me and craves for my society…. Sad changes will come soon enough. Let us be happy while we can….I can’t write more now, my sweet little wife, so good night for the present.

A few days later, Alec organized a private sleeping car in which he and his father could travel by rail undisturbed from Iona, near Grand Narrows on Bras d’Or Lake, all the way to Boston. On a sunny December day, Melville was carefully carried onto a steamer at the Beinn Bhreagh dock, then equally carefully transferred to the sleeping car at the other end. Alec settled his father onto the red plush upholstery of the bunk bed, tucked a couple of woolen blankets over him, and switched on the gleaming brass lamps on the opposite side of the compartment. But the light was too dim for his eyes, so he could not read. He could only stare out at the dark woods and the first snow powdering the hills, and reflect on his father’s life that was visibly seeping away.

It must have been a poignant journey for both Melville and Alec. Melville was now so dependent on the son from whom he had demanded dependence all those years ago. While the sleeping car swayed and rumbled over the rails, he held tight to Alec’s big-knuckled hand and drifted in and out of sleep. For his part, Alec gazed silently at his father’s face—a face that, with its dark eyes, big nose, gruff expression, and bushy white beard, was so similar to his own. Did he recall his resentment of Melville’s attempts to mold him in his own image as a proponent of Visible Speech, and his hurt when Melville scorned his experiments with wires and dynamos? Did he remember his hunger for his father’s approval, even as he struggled to escape Melville’s overbearing presence? Only when Mabel had become the emotional center of Alec s life had Melville lost his hold on his son. But now Alec could recognize what he owed his father. If his father had not insisted that his family leave London, after the deaths of Melly and Edward, he himself would likely not have survived. Without everything his father had taught him about speech and hearing, he might not have invented the telephone. Without the example of his parents’ happy marriage and of Melville’s obliviousness to his wife’s deafness, he himself might have thought twice about marrying a profoundly deaf woman.

When Alexander Melville Bell died, Alec would be the last remaining member of his own family, and the last of the Alexander Bells trained to be a “professor of elocution.” The journey to Washington, with a change of trains at Boston, took more than two days. Melville felt entirely cocooned in his son’s care. Alec felt entirely alone.

The end came in August 1905. Alec was not present, but Mabel was with Melville in his Georgetown house as he struggled to take his last breaths. He was as theatrical in death, she wrote to her husband, as he had been so often in life. He “held up his hand and then spread it down as he does when a thing is finished, the characteristic elocutionist’s gesture, marking the last fluttering breath.”

Alec left no written record of his feelings as he contemplated the passing of his father. It was one of the many occasions in his life when he retreated to his laboratory and refused to examine his emotions because the experience might have been too painful. Instead, in Cape Breton, he plunged into his newest project: the construction of a huge kite that consisted of two banks of tetrahedral cells and was so massive that it required a howling gale to lift it from the ground.