Reluctant Genius (25 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

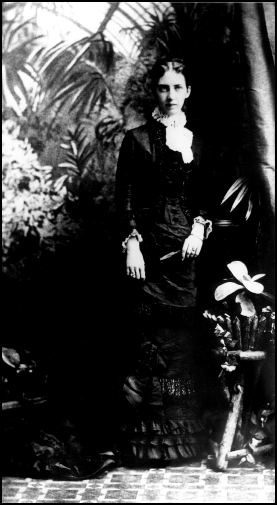

Mabel, aged twenty, in the brown silk dress she wore for the Brantford party.

Gertrude Hubbard’s immediate response was to announce that she would leave her husband in Washington and join her daughter in London as soon as possible. However, Alec solved the servant problem by recruiting Mary Home, his grandfather’s former housekeeper at Harrington Square, to come and live with them. Mabel explained that “[w]e propose to have one servant to do general work and Mary Home will manage her and relieve me of all the trouble while, Alec says, she will let me have my own way in all things. She knows all about the stores and marketing and would see that I did not get cheated…. She can also do a little sewing for me, and go out shopping with me thus saving the expense of a woman like the one I am employing now.” The only problem was that Mary’s front teeth were missing, which made it hard for Mabel to follow what she was saying. Emma, the little maid hired to help Mary, was no easier, because she had such a thick Cockney accent and was “wonderfully stupid about everything outside her own duties.”

By mid-November, Mabel was over morning sickness and back to her own sturdy self. She urged her mother not to come until the spring: “Alec…can take care of me.” Alec had found a house in South Kensington, and toothless Mary Home introduced Mabel to the challenges of housekeeping in the world’s largest and dirtiest city. Mabel was astonished when Mary told her she would need two dozen dusters at least, including “round cloths, kitchen cloths, house flannels and I know not what else.” She still had to come to terms with London’s “blacks,” as Londoners called the flakes of soot that floated in the air, marking everything they touched, inside and outside. Mary Home took Mabel to Hitchcock and Williams’s wholesale shop, “where all the best Dresden table damask comes from,” to purchase tablecloths, sheets, pillowcases, bolster covers, napkins, and half a dozen damask towels. Alec presented his wife with a housekeeping allowance of £10 a month to cover rent, coal, gas, wages, and food (in today’s currency about £700, or US$1,400), and with a book called

Common Sense Housekeeping.

Mabel pored over the esoterica of housekeeping, marveling that “a splendid fire is made with ashes sifted and mixed in a little water with coal dust mixed to a paste,” adding, for her mother’s edification, “It must be baked in the fire and the poker not used.”

The Bells moved into 57 West Cromwell Road on December 1. It was a typical mid-Victorian four-story house, part of a block-long terrace of similar houses constructed of gray brick with creamy stucco facings, each with two chimneys on the roof and a well below sidewalk level with a basement entrance. In those days, West Cromwell Road was an unremarkable street on the edge of London, lined with elm trees and stretching from Earl’s Court in the east to Hammersmith Cemetery in the west. It was, however, safely middle-class, within walking district of the more rarefied (and expensive) neighborhood of Kensington High Street, where Mabel would be able to enjoy well-stocked department stores like Barker’s. Closer to home were the busy little shops along Fenelon Road, where Mary Home could patronize the butcher, greengrocer, bootmaker, and confectioner. West Cromwell Road also had the advantage of being near Earl’s Court Station, on the newly opened District Railway line, which connected the area with the city and all the main-line train stations.

The West Cromwell Road house had seventeen rooms and many modern features, including gas lighting throughout and a bathroom with hot running water on the second floor. To an American eye, the rooms were small and cramped, and Victorian clutter—pots of ferns, china ornaments, knickknacks made of ivory or ebony, occasional tables—added to the claustrophobia. Alec appropriated as his workspaces three rooms, one on each of the upper floors, which he would connect with telephone wires. Only one room was big enough to hold a double bed, and Mabel started fretting about where her mother and sister would sleep when they arrived the following spring. But by the third evening, as she sat in the dining room with the gas jets lit, the heavy curtains drawn, and the brass fender reflecting the flames in the tiled fireplace, Mabel wrote to her mother that life in the new house was “fun.”

Mid-pregnancy, Mabel enjoyed a burst of energy. She turned her attention to organizing domestic routines—key to every Victorian homemaker’s self-image. She established a rigid cleaning routine, with Emma the Cockney maid dusting the study, drawing room, and dining room every day and the halls and bedrooms every other day. Mabel kept Boston standards firmly in mind: “I cannot see that even Cousin Mary would think the house dirty,” she boasted. Next, she drew up a weekly menu of unappetizing monotony: “I had stewed beef for dinner Saturday; Sunday … sirloin of beef, potatoes, brussel sprouts, bread pudding and fruit; Monday the beef warmed, potatoes ditto because I was away; yesterday mutton, potatoes, cauliflower; today we are to have the mutton cold with potatoes and macaroni.” She asked her mother for domestic tips: “I should like your recipe for … floating islands…. How do you make fish balls, and what can I do with the remains of cold chicken?” Two months before her wedding, Mabel had written to Alec’s mother that “like a true Briton [Alec’s] spirit depends on his having a good dinner. I am beginning to learn that my happiness in life will depend on how well I can feed him.” Regular, nutritious meals were one way of providing some stability in both their lives.

Mabel even established some control over Alec’s unconventional working hours. She forced him to get out of bed for breakfast at 8:30 each morning (“It is hard work and tears are spent over it sometimes”), and she persuaded him that, after they had dined together at seven, he would not return to work in his study until 10:00. His wife’s entreaties may have irked Alec, but the daily routine agreed with him. Now that he was married, he was no longer living on his nerves—and it showed. “Why Mamma dear,” Mabel reported, “he had his wedding trousers made larger sometime ago, and who would have thought they would so soon be tight again.” On Christmas Day, he had stooped to extinguish the candles on the Christmas tree, and his trousers had burst. The man who had been skinny since childhood and had weighed only 165 pounds on his wedding day now topped 200 pounds. From now on, he was invariably described, in that wonderful Victorian euphemism, as “majestic.”

After Christmas, Mabel made her first attempt at entertaining. Alec had invited for dinner William Preece, who, as the post office engineer-in-chief, was one of the most learned electrical engineers in the country and therefore an extremely useful business contact. Mabel cast aside cold mutton and macaroni in favor of a much more ambitious menu: jugged hare followed by her mothers famous dessert, floating islands. Her mother had not yet supplied the recipe for floating islands, an exotic concoction of poached meringues on an egg custard, but Mabel fearlessly soldiered on. “Miss Home undertook to stir the custard while I industriously beat the egg whites, of course flurried as I was about Alec, I let her go on until it boiled. That meant ruin. We took four more eggs, and I stirred while she beat. I forgot to stir, and the first thing I knew the milk was all over the floor, that meant ruin No. 2. We tried some more milk and after Herculean efforts the custard got safe through and was sent to cool.”

By now, it was five thirty. Mabel ran upstairs to change, thinking that Mr. Preece would arrive at seven. But just as she started to braid her hair, she remembered that Mr. Preece had been invited for 6 p.m. She pulled on her gown and rushed downstairs again, only to meet Mr. Preece coming up. It was an awkward moment: Alec, who had a bad cold, had stumped off to bed with instructions to be woken only after Mr. Preece had arrived; Mary Home hissed that the hare would not be satisfactorily jugged before seven; the drawing room, Mabel realized with horror, was slowly filling with smoke—Emma, the maid, had forgotten to open the damper before she lit the fire. Mr. Preece beat a hasty retreat down West Cromwell Road, assuring his hostess that he had to make a call but would return in an hour.

Poor Mabel. Her thick hair was falling out of its pins, her dress was disheveled, she was five months’ pregnant, and her first dinner party was heading toward disaster. Her face often wore a look of anxiety as she tried to follow conversations, but she was now in a panic. Nevertheless, she took a deep breath and rose to the occasion. She finished dressing, then set the table herself to ensure it was done correctly (this was a skill young ladies in Boston were taught) and told Emma to stay in the dining room throughout the dinner so there were no periods of

longueur

between courses. Mr. Preece returned, Alec woke up, the hare was cooked. But just as they were about to sit down, there was a ring at the doorbell. It was the doctor, to check on Alec’s cold. Once again, events spun out of control. There was no gravy for the hare (“Mr. Preece was surprised and I was mortified.”) The handle fell off a pitcher of water, causing the contents to soak the table. Alec had barely returned to the table after seeing the doctor when he disappeared again halfway through the meal to see a friend. Emma left the room, so Mabel had no one to help her serve. Half the floating islands custard slopped over the rim of the dish in which it was served.

It was a good thing that all present shared a sense of humor. Mabel wrote a cheerfully self-deprecating account to her mother of her first dinner party as “the worst failure I ever saw.” Mr. Preece forgave the lack of gravy, and was one of the sponsors, a few weeks later, of the special general meeting of the Society of Telegraph Engineers held in London “for the purpose of welcoming Professor Graham Bell to London.” And Alec roared with laughter and hugged his adored wife. Then he described to Gertrude Hubbard his pride in her daughters accomplishments, and their closeness as a couple:“ Mabel has hitherto been so much part of you that it seemed at first like tearing her life to pieces to remove her from your sheltering care. If there is anything that can console me for this cruelty, it is the feeling that the temporary separation has brought her nearer to me—that it has made us more truly man and wife than we could ever have hoped to become in America.” He added that marriage had transformed Mabel from “the helpless clinging girl into a self-reliant woman”—an assertion that reflects more his romantic nature than reality. Mabel had never been either helpless or clinging. However, she too recognized the deepening ties of affection between them: “Instead of finding more faults in him, as they say married people always find in each other, I only find more to love and admire. It seems to me I did not half know him when I married him.”

But even as the marriage flourished, telephone business wilted. Alec and Reynolds could not find a British manufacturer who could produce models to their specifications (“they say the British take a month to do what the Americans do in a week”). By now Reynolds had paid him in full for British patent rights, and Alec finally had a comfortable income from the capital that his father-in-law had invested for him. Alec continued giving public performances, since they yielded both fees and fame. Thousands of people attended his demonstration at the soaring glass Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton for the 1861 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Yet there seemed to be one hurdle after another before the British Bell Telephone Company could be established.

When the bell rang at 57 West Cromwell Road in early January, the elderly Mary Home, knowing her employer would not hear it, hobbled up the basement stairs and along the passage to open the front door. A boy in Post Office uniform handed over a telegram, addressed to Mr. Alexander Graham Bell. It was from Sir Thomas Biddulph, private secretary to Queen Victoria, asking when it would be convenient for Alec to show the telephone to the widowed queen at Osborne House, her residence off England’s south coast on the Isle of Wight. The whole household was galvanized with excitement, as news of this unexpected invitation from the most powerful person in the British Empire filtered up and down the stairs.

Mabel was disappointed to discover that she was

not

invited to attend the demonstration, but Alec was soon preoccupied by the challenge of ensuring crystal-clear transmission between the council room in Osborne House (the Italianate villa designed by the late Prince Albert) and two other sites—a cottage on the Osborne House grounds and the little town of Cowes a mile to the north. On January 14, 1877, singers stationed in Cowes were poised to perform over the wires in the same way that Alec’s Uncle David had performed in Ontario. A local electrician had made the queen her own polished walnut receiver, with little ivory nameplates and gold switches. Alec and Reynolds, splendid in white tie and tails, drove up to Osborne House at 8:45 p.m. and were shown into the Council Room. Meanwhile, Sir Thomas and Lady Biddulph sat by the telephone that had been installed in Osborne Cottage. Alec was frustrated to discover that the telegraph line to Cowes was broken, so the four-part harmonies from the singers stationed there would go unheard. But there was no time to fix this: a footman appeared at the door and announced that the queen was approaching. Minutes later, the swish of voluminous, crinolined skirts was heard, and a short figure appeared in the doorway. The courtiers bowed low as Her Majesty Queen Victoria glided into the room, accompanied by her youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice, and her son Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught and a future governor general of Canada.