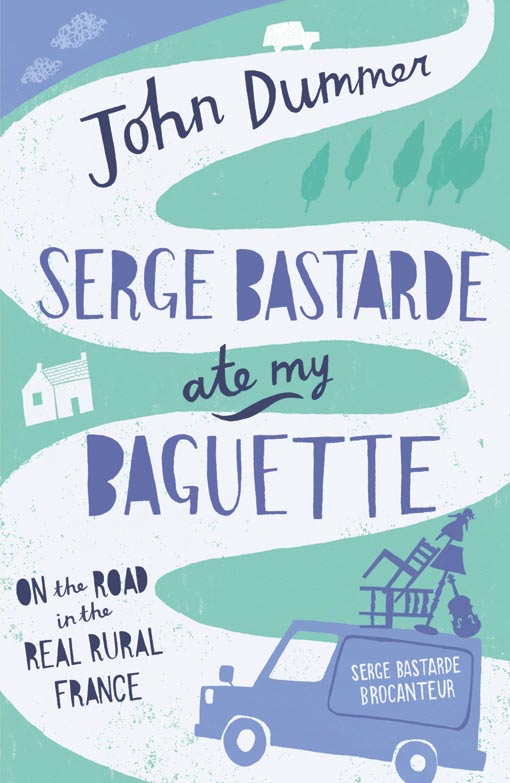

Serge Bastarde Ate My Baguette

Read Serge Bastarde Ate My Baguette Online

Authors: John Dummer

Serge Bastarde Ate My Baguette

On the Road in the Real Rural France

John Dummer

SERGE BASTARDE ATE MY BAGUETTE

Copyright © John Dummer 2009

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of John Dummer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

eISBN: 978-1-84839-953-2

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details telephone Summersdale Publishers on (+44-1243-771107), fax (+44-1243-786300) or email (

[email protected]

).

[email protected]

).

CONTENTS

Preface

1. Pigs and Pegs

2. Police and Prisoners

3. The Honeymoon is Over

4. The Little Wooden Devil

5. Gizzards and Bronze Figurines

6. Snobs

7. Hercules

8. Teddy Bears

9. Bullfights and Monkey Business

10. Tiny Tears

11. Dubious Arts

12. Parasols and Harmonicas

13. Corsets and Coquettes

14. Jive Music and Owls

15. Hauntings, Homesickness and Holy Water

16. The Miracle

17. Camping

18. Pirates and Violins

19. Rings and Romance

20. Handbags and Warriors

21. Into the Wild Blue Yonder

PREFACE

I was beginning to wish I hadn't accepted Serge's kind offer to show me 'the true life of a French broc

anteur

'.

anteur

'.

Serge's surname was Bastarde (I'm not making this up). He had 'SERGE BASTARDE â BROCANTEUR' printed in big letters on the side of his van. He was a short, tough, balding bloke with wiry grey hair and a ready wit. When he found out I was English and that I wanted to start up in the antiques trade he had gone out of his way to be helpful and had taken it upon himself to show me the ropes. A

brocanteur

is the French equivalent of a bric-a-brac or antiques dealer in England, and they have a long tradition of buying and selling in the colourful open-air markets all over France. I found Serge's advice mostly useful and it would have been churlish to have refused his invitation to accompany him on a trip out in the country to 'forage for hidden treasures'. If the truth be known I secretly couldn't resist the novelty of passing time with a bloke called Serge Bastardeâ¦

brocanteur

is the French equivalent of a bric-a-brac or antiques dealer in England, and they have a long tradition of buying and selling in the colourful open-air markets all over France. I found Serge's advice mostly useful and it would have been churlish to have refused his invitation to accompany him on a trip out in the country to 'forage for hidden treasures'. If the truth be known I secretly couldn't resist the novelty of passing time with a bloke called Serge Bastardeâ¦

1

PIGS AND PEGS

'Ooooh, look! They're washing their pig!' It was a touching sight, the epitome of simple country folk togetherness. The whole family â mum, dad, grandma, grandpa and all the kids â around a big stone trough in the yard with their sleeves rolled up. We had come bombing down a quiet country back lane in Serge's old Renault van to arrive at a typical farm

mas

â a house and several large stone barns grouped round a cobbled courtyard with a surrounding wall and big wooden gates. And there they all were, having the time of their lives.

mas

â a house and several large stone barns grouped round a cobbled courtyard with a surrounding wall and big wooden gates. And there they all were, having the time of their lives.

I could see the old sow's head and her back over the side of the trough. Pigs must get really dirty plunging about in all that mud and need a good washing now and again. Serge tooted his horn and they turned as one to wave at us, happy smiling faces enjoying their carefree country living. But now, with all their hands in the air, I realised just how mistaken I was. Blood and gore was running down their arms. These people weren't washing their pig at all. The miserable animal had just been slaughtered and they were in the process of disembowelling it.

As we drove through the gates and bumped over the cobblestones I could see a couple of legs and trotters sticking up and a long, livid slit in the carcass.

This was exactly the sort of confrontation with the realities of animal husbandry that had turned me and my wife Helen into vegetarians since moving to France. In fact, as a reformed alcoholic ex-smoker vegetarian who disliked sunbathing, I sometimes wondered what the hell I was doing living in France at all.

The farmer stood up and came towards us with a quizzical smile, followed closely by two of the youngest kids, a little boy of about four and a girl who might have been his twin sister. Their faces were spattered crimson. The farmer lifted his elbow to be shaken to avoid smearing our hands with congealed blood and waited to see what we wanted. Over in a corner by the barn a vicious dog that looked like a cross between a German shepherd and the Tasmanian Devil fought to break free of its chain and devour us.

Serge and I had been touring around all morning, 'cold calling' on the most far-flung farms and cottages. Serge would strike up a conversation with the inhabitants to ask if they had any old furniture or junk they wanted to get rid of. If his question elicited a lukewarm response he would pull out a thick wad of euro notes and wave them temptingly under the householder's nose. So far this technique had yielded a few old chairs, a broken-down kitchen table and a rusty standard lamp. But Serge remained undaunted. Maybe our luck was about to change.

He reached down, ruffled the little girl's hair and beamed his sincerest smile at the farmer. '

Bonjour, m'sieu

. We are carrying out some important work for the commune,' he lied. 'They have asked us to visit all the farms in this vicinity and perform a much-needed service, to pick up any old unwanted furniture and stuff that needs to be got rid of. We have already helped out some of your neighbours.' He waved vaguely towards the van. 'Might you have any old bits and pieces you don't want? Things that are hanging around the house gathering dust that we can take off your hands?' The farmer wiped his hands on his shirt and appeared to be considering the question. The dog had decided we were no threat and stopped barking. The rest of the family carried on with their grisly work. 'We're not here to waste your time â we're honest, professional people. We'll pay you for anything of value.'

Bonjour, m'sieu

. We are carrying out some important work for the commune,' he lied. 'They have asked us to visit all the farms in this vicinity and perform a much-needed service, to pick up any old unwanted furniture and stuff that needs to be got rid of. We have already helped out some of your neighbours.' He waved vaguely towards the van. 'Might you have any old bits and pieces you don't want? Things that are hanging around the house gathering dust that we can take off your hands?' The farmer wiped his hands on his shirt and appeared to be considering the question. The dog had decided we were no threat and stopped barking. The rest of the family carried on with their grisly work. 'We're not here to waste your time â we're honest, professional people. We'll pay you for anything of value.'

The farmer's attention was beginning to wander. He glanced back at his pig in the trough. He didn't want to appear rude. The French habit of

la politesse

is a deeply engrained one. He rubbed his hand across a bristly chin. 'No, nothing like that,' he said. 'I'm sorry, I wish I could help you, butâ¦' Serge flashed me an ironical smile. When he reached in his pocket and pulled out the wad of notes, the effect on the farmer was quite remarkable. All thoughts of sausages, bacon and smoked ham were instantly wiped from his mind. His eyes opened wide, hypnotised by the money. 'Of course, we'll pay you for anything we take⦠in cash,' said Serge. He fanned the notes in the air.

la politesse

is a deeply engrained one. He rubbed his hand across a bristly chin. 'No, nothing like that,' he said. 'I'm sorry, I wish I could help you, butâ¦' Serge flashed me an ironical smile. When he reached in his pocket and pulled out the wad of notes, the effect on the farmer was quite remarkable. All thoughts of sausages, bacon and smoked ham were instantly wiped from his mind. His eyes opened wide, hypnotised by the money. 'Of course, we'll pay you for anything we take⦠in cash,' said Serge. He fanned the notes in the air.

'What sort of things are you looking for?' asked the farmer. 'I suppose we might have some stuff we don't want.'

'I know,' said Serge. 'Why don't we take a walk round the house? I can point out the sort of thing we'd be interested in and what it's worth. Then you can see if you'd prefer to keep it or take the money.'

The farmer liked this idea. We followed him across the courtyard past the rest of the family, who carried on cheerfully hacking away at the dead pig, piling up a mess of intestines and vital organs on a stone slab.

The farmhouse was cool and shady after the hot sun and it took a moment for my eyes to adjust. We were standing in a typical French farm kitchen running into a sparsely furnished living room. The floor was tiled and, apart from a kitchen table, a few worn easy chairs and a television, there was no clutter to speak of and very few decorations of note: a cheap kitchen clock and the local fireman's calendar pinned to the wall; a palm cross; a small plaster figurine of St Bernadette of Lourdes in an alcove. These were honest, hard-working farming folk. They were out in the fields most of the day. The chances of finding any of the valuable antiques Serge was expecting were slim.

I was beginning to feel like an evil money-grabbing bastard. Serge was acting like his surname and this was the first and last time I intended coming out with him on such a cheapskate mission. Helen and I would stick to buying our

brocante

in the auction rooms in future, even if you did have to pay through the nose for it. At least it left you with a clear conscience. Serge was looking around, unimpressed. 'Sure you haven't got any old furniture or clocks you don't want? We pay quite good money for old bronzes, things like that.'

brocante

in the auction rooms in future, even if you did have to pay through the nose for it. At least it left you with a clear conscience. Serge was looking around, unimpressed. 'Sure you haven't got any old furniture or clocks you don't want? We pay quite good money for old bronzes, things like that.'

The old boy shook his head and racked his brains.

'What about upstairs? Any uncomfy old oak beds you don't need?'

I couldn't believe Serge was wasting the bloke's time like this. He'd seen the kids in the yard. This family needed all the spare sleeping accommodation they could muster. I wanted to get out of here and leave these good people to carry on preparing their porky comestibles for the coming winter. They didn't deserve to be bothered by creeps like us. I was about to let Serge know how I felt when the old boy's face lit up. 'We have got some old furniture which we dumped out in the barn a few years back,' he said. 'We needed the room and it was a bit gloomy.'

Serge threw me a meaningful look. 'That's the sort of stuff we're after; gloomy old furniture. You've got it right there, all right. Horrible stuff! That's exactly what the commune told us to pick up and get rid of. Clean up all the old junk, the mayor said.'

'I suppose it could be worth something to someone,' said the farmer as we followed him through the back door to some broken-down outbuildings. 'It's good sturdy stuff⦠been in my family for as long as I can remember, maybe even before the Revolution, it's that old.'

Serge winked at me behind the farmer's back and rubbed his hands together in glee. There were pigeons roosting in the eaves and the door was hanging off its hinges. When the old boy shouldered it open with a bang, there was an explosion of feathers and a couple of squawking chickens tore through our legs. Inside, the air was thick with floating feathers and powdered chicken excreta. Brilliant shafts of sunlight shone down through the murky fog of dust onto strange, bulky shapes piled up high against one wall. When I drew in a breath I could feel a film of chicken shit forming at the back of my throat.

The farmer made a sweeping gesture. 'Well, there it all is. If you think you might be able to do something with itâ¦'

As the dust began to settle, it was patently obvious that these bulky shapes were not the pieces of priceless furniture we had imagined, but huge piles of sidepieces, backs, cornices, legs, doors and other assorted parts. Some well-meaning individual had reduced this load of 'gloomy old furniture' to easily transportable antique flat packs. Serge stood with a look of horror and disbelief on his face. It was the first time I'd seen him speechless.

Other books

To Love a Stranger by Mason, Connie

A Disorder Peculiar to the Country by Ken Kalfus

Where the Heart Is Episode Three by Jean Lauzier

Love in a Small Town by Curtiss Ann Matlock

Family Pictures by Jane Green

How to Be Alone by Jonathan Franzen

40 Juicing Recipes for Weight Loss and Healthy Living by Jenny Allan

Chase the Stars (Lang Downs 2 ) by Ariel Tachna

The Four of Us by Margaret Pemberton