Reluctant Genius (37 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

With her parents and her only remaining sister, Grace, living close by, Mabel felt safely cocooned by family. She herself was gradually emerging as the matriarch of the clan, replacing her mother, who was losing her sight. Hubbard-Bell ties became even closer in 1887 when Alec’s cousin Charlie, whose wife, Roberta Hubbard, had died in 1885, married his former sister-in-law Grace. Gardiner Hubbard must have pondered the irony that, despite his initial doubts about Bell marriages, three of his four daughters had become “Mrs. Bell.”

The balance of Mabel and Alec’s marriage shifted with the passing years: as Mabel matured, the ten-year age gap between her and her husband shrank in significance. Cool-headed in a crisis and the source of inexhaustible reassurance to her volatile husband, Mabel kept her husband grounded. When Alec erupted with exasperation about the fire going out in his study, Mabel soothed him and suggested that, instead of blaming the staff, he might even relight it himself. When Alec withdrew into his researches, Mabel coaxed him back into the family circle with maternal solicitude. “Please darling, make an effort to be more sociable,” she urged him, “and go to see people and have them come to see you… . [P]lease try and come out of your hermit cell.” When Alec overtaxed himself by working all night, she scolded him: “I am frightened to think where you will be when sickness comes, as come it must sometime if you continue your present irregular life.”

Mabel knew that the private Alec was a much more insecure and anxious man than his public persona at white-tie dinners or Wednesday-evening get-togethers suggested. “If anything went wrong,” their daughter Elsie recalled years later, “Father had to be looked after first, while Mother took charge of the situation.” Mabel was aware that he hungered to make more contributions to scientific knowledge and that his endless health complaints were often related to his frustrations. He

always

got a headache when he had to give a speech or meet new people. Alec acknowledged his emotional dependence on his wife in a letter he wrote to her in June 1889:

Oh Mabel Dear, I love you more than you can ever know, and the very thought of anything the matter with you unnerves me and renders me unhappy. My dear little wife, I feel I have neglected you. Deaf-mutes, gravitation or any other hobby has been too apt to take the first place in my thoughts, and yet all the time, my heart was yours alone… . I want to show you that I really can be a good husband and a good father, as well as a solitary selfish thinker… . You have grown into my heart my darling and taken root there—and you cannot be plucked out without tearing it to pieces.

A year later, when he was forty-three and Mabel thirty-three, Alec deplored his own tendency to bury himself in whatever project obsessed him but took refuge in self-pity to excuse his conduct: “Our minds are apart and it is my fault. I remain solitary and alone—and every year takes me farther from you and my friends and the world—and I seem powerless to help. But for you I should lead the life of a hermit, alone with my thoughts. I hang like a dead weight on your young life, and crush you. What can I do? Is it in me to be young again? I fear that I am older than my years, while you my dear are young. What can I do to now make you happy?”

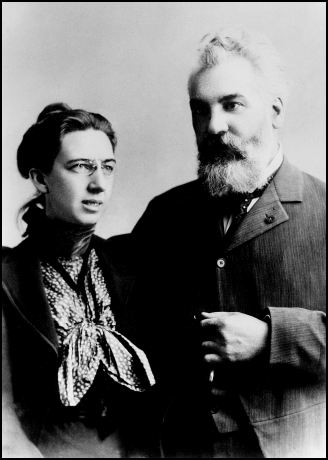

Alec and Mabel Bell in the late 1880s.

Charles understood the dynamics of the marriage perhaps better than anybody. “Only those who were closely associated with the daily life of Mr. Bell,” he wrote after the death of his employer, “knew how much his success, in the things he was interested in, depended on the never failing care, constant watchfulness over his health, his recreation and his hours of study, by Mrs. Bell. They were indeed united for life.”

Most of the time Mabel played the traditional role of the dutiful and admiring wife—the role her mother had played for her father. She made sure that the household revolved around Alec’s needs, even if this meant that everyone had to tiptoe past his bedroom until the early afternoon or that he kept everyone except her awake past midnight by playing Beethoven vehemently on the grand piano. She tried to allay his anxieties by reassuring him that rivals like Edison and Gray were just “inventors, and you are a scientific man.” But sometimes she could not suppress her resentment at the way that Alec left so much to her and took her and their daughters for granted. When he was pursuing a new idea or caught up in his latest projects, everything else went by the board, including sleep and children.

"My dear Alec, I do think you are behaving shabbily all round,” reads one undated letter, written during one of their frequent separations.

Why will you always break your word to your wife at the slightest provocation…. I really need you badly here and have not been feeling quite well for some days, and had nightmares every night so that I am frightened being alone. .. . They are all laughing at me here for believing you would keep your promise [to join the family]. They think it a good joke, and oh Alec, it hurts. I never dare say a word to you for you always say I am scolding and so sulk and will not hear…. Your loving but distressed wife.

P.S. It is so nice being rich, please don’t spoil it for me by feeling that perhaps it is a curse instead of a blessing because if we were poor you would have to work hard and regularly.

Mabel couldn’t help contrasting the way that Alec treated her with the way that her father treated her mother, or Alec’s cousin Charlie treated her sister. On a later occasion, she wrote reproachfully, “I realize as I see Mama and Papa, Grace and Charlie together, how little you give me of your time and thoughts, how unwilling you are to enter into the little things, which yet make up the sum of our lives. There are so many more of those things than you realize, which I cannot decide alone. I feel as if I were giving more and more to others the dependence for help and advice that should be yours.”

There were undeniably times when Mabel’s spirits drooped, although she was an optimist by temperament. Her sisters had always been her closest friends, and she was often lonely now that two of her sisters were dead and her husband was frequently absent. The women in Washington society admired the way she had overcome the handicap that deafness presented, but they did not befriend her. Not only was her speech hard to understand, but her shyness and Boston aloofness meant that she wouldn’t (or couldn’t) play their social games—comparing invitations, fashions, and houses.

And there was another issue, only hinted at in Mabel’s and Alec’s letters to each other. Mabel was still young, young enough to try for the longed-for son. But she had suffered two premature births and the loss of both infants, and her physician had warned her after Robert’s death that she should not yet attempt a fifth pregnancy. In the Bells’ correspondence, there are veiled references to the contraceptives (pessaries, abstinence) on which she relied until her doctor told her she was strong enough to try again. There are also hints of Alec’s frustration.

“Dear, dear Mabel,” Alec wrote to her in 1885. “My true sweet wife— nothing will ever comfort me for the loss of those two babes for I feel at heart that

I was the cause.

I do not grieve

because they were boys,

but because I believe that my ignorance and selfishness caused their deaths and injured you… . After [the first child's] death

I

prevented you from fully recovering

and gave you another child before you were well. You have not even yet fully recovered and I believe you never will until you have had a complete and prolonged rest.”

Volatile and needy, Alec hungered for his adored wife at the same time as he feared another conception that might put her health at risk. Yet celibacy appears to have been beyond him. Perhaps distance was the only remedy? “I pause here in New York,” he wrote, “and ask myself whether it was best for you that I should return just now. Think seriously of it my darling wife.” Only separation, he suggested, would give Mabel the chance to regain her strength and then “have another sweet baby-face smiling in your arms.”

Allusions to Mabel’s longing for another baby and to Alec’s fear that sexual intercourse might damage her health appear in their letters for the next decade. In a pre-contraception era, Alec’s fear was probably justified. But her loneliness and his fear of intimacy created tensions, especially when they were apart. In 1888 Mabel wrote to Alec, “I wonder do you think of me in the midst of that work of yours of which I am so proud and yet so jealous, for I know it has stolen from me part of my husband’s heart, for where his thoughts and interests lie, there must his heart be.”

Despite Mabel’s hopes, despite some mysterious surgery that she underwent in 1891, despite assignations with Alec when she was convinced she was ready to conceive, Mabel would never have another child.

Summers in Baddeck gave the Bells the opportunity to shuck off the social pressures and marital stress that Washington induced. Memories of the lake’s misty shoreline or the sun’s last rays on Red Head were a psychological balm during winters stuffed with social engagements, speeches, interviews with lawyers or journalists, children’s illnesses, domestic crises, family obligations, disappointments. In 1888, even as Mabel reproached Alec for, once again, accepting too many out-of-town speaking engagements at schools for the deaf, she reminded him that soon they and their daughters would be at their island refuge: “I live in hope that you will not quite forget me and that we may pass many another summer like the last [in Baddeck] when we had thoughts and interests in common.”

There was, however, one subject to which Alec was devoted heart and soul, and for which Mabel had little sympathy.

Chapter 15

H

ELEN

K

ELLER AND THE

P

OLITICS OF

D

EAFNESS

1886-1896

O

ne day in 1886, there was a knock on the door of the Bells’ Washington home. The housekeeper opened the door to find a well-dressed gentleman clutching the hand of a small girl. The six-year-old child was neat and pretty, with a chestnut cloud of corkscrew curls. But there was a slight bulge to one eye, and the other eye wandered strangely. She appeared unaware of the stranger in front of her, or of the invitation to enter the house.

Alexander Graham Bell, summoned from his third-floor study, joined the housekeeper at the door. The gentleman was Captain Arthur H. Keller, a former Confederate officer who owned a run-down cotton plantation in Alabama and edited the local newspaper. Captain Keller had dropped a note at the Bells’ house the previous day, asking if he could bring his daughter to meet Dr. Bell. Alec, who never refused to see a deaf child, had immediately sent a note of assent. Now he politely shook Captain Keller’s hand, then knelt on the floor so he could say hello to Helen. Her busy, curious hands rapidly explored the territory of his face—the bushy beard, strong nose, and thick mustache. Her small fingers rested on his lips as he said her name, then touched his stiff collar, soft tie, tight waistcoat, and watch chain. Her responsiveness did not register in her face; he later described it as “chillingly empty.” The party moved into the parlor, with Helen holding Alec’s hand. As soon as he sat in his big wing chair, she scrambled onto his lap and her fingers, like little mice, resumed their exploration. She found Alec’s pocket watch, which chimed on demand, and when he set it to chime, the vibrations finally elicited the ghost of a smile.

This meeting was an epiphany for Helen Keller, who would become one of the most admired celebrities of the twentieth century. “Child as I was,” she would write in her 1903 memoir,

The Story of My Life,

“I at once felt the tenderness and sympathy which endeared Dr. Bell to so many hearts, as his wonderful achievements enlist their admiration. He held me on his knee while I examined his watch, and he made it strike for me. He understood my signs, and I knew it and loved him at once. But I did not dream that interview would be the door through which I should pass from darkness into light, from isolation to friendship, companionship, knowledge, love.”

At this point in her young life, Helen was untutored, unmanageable, and probably very unhappy. Born in the remote Alabama town of Tuscumbia, on the Tennessee River, she had developed at nineteen months what doctors at the time called “brain fever” (probably scarlet fever or meningitis) and was expected to die. She recovered, but she could no longer see or hear anything. Helen had only the senses of smell, taste, and touch with which to explore her environment, and with every passing year she grew more screamingly frustrated with her limitations. Her parents were deeply distressed by their “little bronco,” as they called her, whose behavior and understanding of the world steadily deteriorated.

Then Helen’s mother, Kate Keller (who by now had a second daughter), read in Charles Dickens’s

American Notes

of Boston-based Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe’s success with Laura Bridgman. Dr. Howe had died in 1876, but Kate Keller was as determined to help her disabled daughter as the Hubbards had been twenty-three years earlier to help their daughter Mabel. Just as the Hubbards had hoped that Dr. Howe might provide a key to their deaf daughter’s education, so Mrs. Keller hoped that the answer to Helen’s problems might be found at Boston’s Perkins Institution for the Blind, founded by Dr. Howe, where Laura Bridgman still lived. Kate Keller also heard of an eye surgeon in Baltimore who was said to have helped blind children recover their sight. So she sent her husband, Arthur, to find help for Helen in the distant (and still not particularly welcoming) northeast. The Baltimore surgeon could do nothing for the little girl, but he recommended that the Kellers consult the famous inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who had a particular concern for the education of the deaf. Captain Keller and Helen, along with Arthur Keller’s sister, trekked on to Washington, in the hope that Alec might recommend a teacher for the girl.