Reluctant Genius (35 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

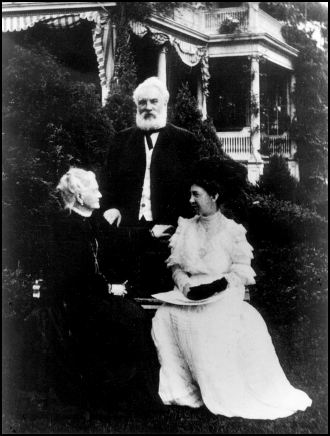

Crescent Grove, after the Bells had jacked up the Baddeck cottage and added another story.

Alec purchased Crescent Grove and enlarged it by jacking it up and building another story underneath it. The locals, who watched Bell family activities with amused skepticism, dubbed it “the cottage on stilts.” However, Alec already had his eye on another property: the headland called Red Head, across the bay from Baddeck. One bright August day, when the sun was sparkling on the lake and there was not a cloud in the deep blue sky, he and Mabel hired a wagon and drove over to Red Head, then found a rough trail there that took them to the other side. “Fancy driving over the crest of a mountain, the highest for many miles,” Mabel told her mother, “and seeing the land stretched out on every side of you like a map. Hills and valleys, water and islands are all around, the hills of Sydney on one side, Boularderie Island right at your feet with the Big and Little Bras d’Or entrances on either side…. Immediately beneath, peeping through its fringing trees with sharp contrasts of white plaster cliffs, lay two lovely little harbors.”

Both Alec and Mabel were captivated by the extraordinary beauty around them. One look at her husband’s face convinced Mabel that this was a place he could be happy. Alec was already planning how to take possession of this magical headland, and over the next seven years, he would acquire it, a few acres at a time. He took psychological possession of it, too: he would soon rename it “Beinn Bhreagh” (pronounced “ben vreeah”), which is Gaelic for “Beautiful Mountain.” Beinn Bhreagh and Baddeck provided the kind of therapeutic release for which Alec’s tightly wound temperament yearned. The solitude and natural splendor also gave him a new lease on life: they would stimulate the kind of frenzy of invention he had enjoyed during the 1870s.

Mabel confided to her mother that her husband “is quite a different person from what he is in Washington…. Here he is the life and soul of the party…. He is forever on the go; at night when all are sleeping, he is paddling about but he is up again at his usual hour.” At Baddeck, both Mabel and Alec lived in the present. Whenever they were far from Cape Breton, their thoughts would wander back to the sound of the wind in the fir trees and the long view down the vast inland seas. “It is strange what a hold Baddeck has already on Alec,” Mabel wrote to Melville Bell in June 1887 from Washington. “The other night when Alec was in pain and fever, he bade me remember if anything happened that he would be buried nowhere else except at the top of Red Head.”

Chapter 14

A S

HIFTING

B

ALANCE

1887-1889

E

ach fall, the Bells were pulled back to Washington. In 1885, Alec had to return to face the Pan-Electric Telephone Company’s assault on his patent and his reputation. He was outraged by the Pan-Electric suit, and sat up for several nights writing a stinging letter to the U.S attorney general. “Poor Alec,” Mabel wrote in her journal that November, “all this week he has been working hard and drawing immense drafts on the reserve of health and strength laid up this summer…. He has not taken a single meal with us all week.”

The case was still grinding on in January 1887 when the Bells faced another Washington crisis. Early one freezing-cold morning, a policeman noticed flames creeping along the mansard roof of 1500 Rhode Island Avenue. The fire had begun in a grate, then traveled into the supporting timbers in the roof. The policeman gave the alarm, which woke the Bells’ cook, maid, and nursemaid. In a panic, they rushed up and down stairs, shrieking “Fire,” shaking the children awake, and banging on Mabel’s bedroom door. But Alec was out of town and Mabel slept on, unconscious of the danger, until Sheila, her Yorkshire terrier,jumped onto her bed. When Mabel realized what was happening, she displayed her usual presence of mind: her priorities were her children and Alec’s books. First, she told Nellie to dress Elsie and Daisy and take them and the dog across the road to a neighbors house. Then, pulling on her new white cashmere coat and leaving her brown hair loose on her shoulders, she went off to find the firemen and instruct them that their most persistent efforts must be directed to saving her husbands study and library, on the third floor. She made sure they did what she asked, pretending she couldn’t understand their pleas to leave the burning building until she was finally driven out by the smoke. By then, the interior of the mansion was drenched with water that quickly froze solid: the exterior of the house was encased in an armor of ice, and icicles as large as a man’s leg hung from the gutters. Meanwhile, across the road, Elsie and Daisy watched the “magnificent sight of the flames leaping into the sky from the roof.” Daisy never forgot the “beautiful… way they swirled around in a little turret, which was my father’s study.”

Early the next morning, Alec was awakened in his hotel room by a bellboy with a telegram from Gardiner Hubbard. It read, “Your house is on fire, Mabel and the children are safe.” Never at his best when woken early, Alec sleepily asked for a train timetable. Informed that there was no train to Washington for four hours, he turned over and went back to sleep. When he finally arrived in the capital, he found his wife infuriated by newspaper reports that described her as rushing out of the house in her nightgown. But he also found most of his library intact.

Alec’s third-floor study, however, was a mess. After negotiating the charred staircase and the squelching carpet, the inventor stood in the doorway, staring in dismay at the litter of sodden notebooks, scraps of paper, and old letters covered in a layer of ice three inches thick. Mrs. Sears, the housekeeper, had hired some men from a nearby rooming house to rip up carpets and clear the debris. Among them was a tall, good-looking African American from Virginia, an eighteen-year-old called Charles Thompson, whom she had put in charge of the study because he could read and write. Half a century later, Thompson remembered this turning point in his life: “During the late afternoon the door of the study was pushed open; turning around to see who had entered, I faced a tall, heavily built man with black hair and black beard mixed with gray. ’Ah ha, here you are; is this Charles?’ ’Yes, Sir.’ ’Well, Charles, I am Mr. Bell, how are you?’ extending his hand with a genial smile, he shook my hand as if he had known me for years.” To a young man accustomed to being treated as a second-class citizen, this courtesy was extraordinary: “I loved Mr. Bell from that moment, and if I had left that house that day never to see him again I never would have forgotten that handshake; it electrified my whole being.”

Alec quickly ascertained that Charles could read his own untidy scrawl. “Ah ha!” he said, when Charles read the notes without hesitation. “Now young man, you have the most important work of all the people employed in this house. This room contains a lot of important papers, in fact, all of my important papers bearing on the work in which I am now engaged is in this room.” Standing in the middle of the chaos, Alec fixed his intense eyes on his new employee, and issued precise instructions: “Don’t throw away any scrap of paper, however small, that has any figures, writing or drawings on it, put everything in a basket, or box, and when you are leaving in the evening bring them to my room.” The young man carried out these instructions so conscientiously that Alec decided to employ him permanently. Charles would remain with the Bells for the next thirty-five years, looking after everything from travel arrangements to Alec’s wardrobe, and always greeting his employer with the same words that Alec used as a telephone greeting: “Hoy! Hoy!”

Charles’s most significant contribution to the household, however, was that he lifted from Mabel’s shoulders the full weight of dealing with her husband’s eccentricities and obsessive observance of rituals—rituals that became more entrenched each passing year. “His daily routine or ’schedule’ as he used to call it,” observed Charles, “was adhered to in the most minutest details.” Within months of Charles’s arrival in the household, as he recalled in a memoir he wrote in 1922, he learned that “any changes by accident, or intent, would upset [Mr. Bell] for the entire day sometimes mentally as well as physically. To call him before nine o’clock in the morning usually gave him a bad headache. But not to call him at nine, and to tell him the exact time was even worse, as he often explained to me—because it left him in doubt as to the exact time that I did call him, and would cause him to lose confidence in trusting me to help keep up his schedule.” Charles would ensure that when Alec did finally rise, his breakfast tray, the morning mail, and the newspapers were waiting for him on a table in his study. Alec insisted on remaining undisturbed while he ate his cold oatmeal (never rolled oats) served with brown sugar and cream on plain white (never patterned) china, and read the papers. If someone did come in and start talking to him, he was likely to go straight back to bed. “He told me many times that he never felt really awake until he had finished his breakfast, read the papers and lighted his cigar or pipe.”

Once these morning rituals were complete, Alec would press three times the bell that communicated with the kitchen three floors below; this was a signal that Charles should remove his breakfast tray and tell Alec’s secretary to go up. After Alec had dealt with his mail, he would dictate an account of the events of the previous twenty-four hours. Then he would get back to his researches on deaf issues, or he would disappear to the Volta Laboratory. “He never liked for any one to knock on his door before entering the room,” Charles always remembered. “If he was following a train of thought and there was a tap on his door, his attention being diverted to the noise, he very often lost the thread and for days would not be able to pick it up again.” Alec once told Charles, “Thoughts, my dear sir, are like the precious moments that fly past; once gone they can never be caught again.” Charles often saw his employer work for up to twenty-two hours without sleep, ignoring his wife’s request that he join her and any guests (usually Hubbard relatives) for dinner.

Any disturbance was such anathema to the telephone’s inventor that he never had a telephone installed in his own study—the bell might have triggered a migraine. He could not stand chiming clocks either. His obsession with his own routine made him maddening to live with. One morning, Mabel asked why every single clock in their mansion was stopped. Her husband told her, “I had an awful time with those clocks last night…. I could not work for the noise, so I went around and stopped them all.” Oblivious to ticks and chimes, Mabel needed to be able to tell the time. She found a clock mender to remove all chiming mechanisms.

After the fire, Mabel refurnished the Rhode Island Avenue mansion, and the family returned there. But the fire had spooked Mabel. “Mother decided it was too big a house for her anyway,” her daughter Daisy wrote later. So in 1889, it was sold to Levi R Morton, vice-president of the United States under newly elected Republican president Benjamin Harrison. The Bell entourage spent the next two years in rented accommodation on nearby 19th Street while they watched their new house being built at 1331 Connecticut Avenue. The new house was designed by the fashionable firm of architects Hornblower and Marshall, who were responsible for changing the streetscapes of Washington in the 1880s and 1890s with their designs for dozens of residences for prominent Washingtonians, including the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum and the mansion that today houses the Phillips Collection. Mabel loved the location of the new house: her sister Grace lived next door and her parents’ townhouse was across the road. Mabel and Alec finally moved into their rather plain, four-story dwelling, built of red brick and stone, in 1892. Soon their little girls were sliding down the banisters of the spiraling oval staircase and Alec was enjoying musical evenings in the parlor. This was their Washington home for the rest of their lives.

By 1888, it was evident that Alec would emerge unscathed from the Pan-Electric suit. Yet frustration and dismay continued to gnaw away at him, as he felt time passing without his making any further contributions to science. It was now fourteen years since he had conceived of the telephone, and eight years since he had dreamed up the photo-phone. Had his brain slowed down, his imagination ground to a halt? Admittedly, deaf studies preoccupied him, but he was still scribbling ideas in his notebooks. The trouble was, he kept telling Mabel, he simply didn’t have the time or the qualified assistance to develop them properly.