Reluctant Genius (38 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

At their first meeting, Alec could see that this child, despite her blank face, nursed a huge curiosity about the world. As soon as she tired of his watch, she scrambled off his knee and started a restless tour of the library, touching and patting every object and piece of furniture she encountered. Alec watched her with both paternal sympathy and scientific detachment. This was a fascinating example of an individual learning new ways to negotiate her world. He decided that he should consult the other great Washington expert on deafness, Edward Miner Gallaudet, on the right course of action for her.

Gallaudet was superintendent of Washington’s Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, founded in 1864. Soon after Alec had moved to Boston in 1871, he had encountered Dr. Gallaudet at the prestigious Clarke Institution at Hartford, where Alec had given a demonstration of the Visible Speech system. Gallaudet, ten years older than Alec and with appointments at both these institutions, was a firm supporter of sign language, which his father, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, had introduced into the United States. He insisted on the intellectual superiority of signs over words, though he did allow both sign language and lip-reading (or “oralism,” as it was known) to be taught at the Columbia Institution. In 1872, he was so impressed by the young Scots immigrant’s teaching methods that he invited Alec to come and teach in Washington at the Columbia Institution. Seven years later, when Alec and Mabel established their home in Washington, Alec wrote to Gallaudet to renew their acquaintance. Gallaudet sent a warm reply: “I should be very happy to have you connected with the work of this college should you take up your residence in Washington.”

During the Bells’ early years in Washington, the two men’s relationship was friendly and respectful. In 1880, the Columbia Institution awarded an honorary degree to Alec. He and Gallaudet had much in common. Both had deaf mothers, and both were motivated by the need for more educational facilities for the deaf. The Gallaudets dined with the Bells from time to time, and Gallaudet attended Alec’s early Wednesday-evening soirées.

Alec dashed off a note to Gallaudet: “Mr. A. H. Keller of Alabama will dine with me this evening and bring with him his little daughter … who is deaf and blind and has been so from nearly infancy. He is in search of light regarding methods of education. The little girl is evidently an intelligent child and altogether this is such an interesting case that I thought you would like to know about it … and [I] hope you may be able to look in in the course of the evening.” Neither Gallaudet nor Mabel, who was probably present at the dinner, left any record of what they thought of this “interesting case.” Since Helen was blind as well as deaf, sign language would have had no place in the two men’s conversation about how to help her. But on the strength of his encounter with Helen, Alec judged her educable. He suggested to Captain Keller that he ask Michael Anagnos, now director of Boston’s Perkins Institution, to recommend a teacher for Helen. Anagnos recommended a remarkable twenty-year-old former Perkins pupil called Annie Mansfield Sullivan, who had spent four traumatic years in a Massachusetts poorhouse as a child and had been near-blind until recently because of trachoma. Annie had become a new person at Perkins, thanks to surgery to improve her vision. She learned Braille and the manual alphabet, and spent a great deal of time with Laura Bridgman, studying the instruction methods that the late Dr. Howe had used to teach Laura. She had the skills required to educate Helen.

Annie Sullivan agreed to move to Tuscumbia and live with the Keller family as Helen’s full-time teacher. At first she was almost defeated by a child who threw cutlery, pinched, grabbed food off dinner plates, and hit Annie herself so hard that one of her front teeth was knocked out. Yet within weeks, Annie had engaged Helen’s intellect. An intense, symbiotic relationship blossomed between stubborn, emotionally starved Annie and the bright little girl. To Helen Keller, Annie was her extraordinary “Teacher,” who would “reveal all things to me, and, more than all things else … love me.” The rest of the world would soon know Annie, in Mark Twain’s phrase, as “the miracle worker.”

Annie started by teaching Helen the one-handed manual alphabet that Annie had learnt at the Perkins Institution. This alphabet, in which letters are denoted by the different position of fingers, is different from both the English double-handed manual alphabet, with which Alec communicated with his mother, and the “glove” alphabet that Alec had taught George Sanders in Boston. However, all three of these manual alphabets entail spelling out words letter by letter, and so (unlike sign language) belong to writing rather than to speech.

Eight months after Annie had arrived in Tuscumbia, Helen’s father, Captain Keller, wrote to Alec, It affords me great pleasure to report that her progress in learning is phenomenal and the report of it almost staggers one’s credulity who has not seen it.… [Within a month of Annie’s arrival] the little girl learned to spell about four hundred words and in less than three months could write a letter, unaided by anyone. In six months she mastered the “Braille” system which is a cipher for the blind enabling them to read what they have written. She has also mastered addition, multiplication and subtraction and is progressing finely with Geography.… I send you a picture of Helen and her teacher and also a specimen of her writing believing you will be glad to hear again from the dear little treasure.

Helen’s ability to learn was far in advance of anything that anybody had seen before in someone without sight or hearing. From the start, Helen was a writer: she relied on a symbolic knowledge of all physical reality that she acquired through Annie’s spelled-out words. She learned oral speech only painstakingly years later, and she was never easily understood. But she began writing almost as soon as she had an elementary vocabulary.

By 1890, Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan were living in Boston, at the Perkins Institution, and for the first time in her life Helen found herself among children with disabilities similar to her own. The sense of belonging was a revelation to her. “I was delighted to find that nearly all my new friends could spell with their fingers,” she wrote in an article entitled “My Story,” for the January 1894 issue of the magazine

The Youth’s Companion.

“Oh, what happiness! To talk freely with other children! To feel at home in the great world! Until then, I had been a little foreigner, speaking through an interpreter, but in Boston … I was no longer a stranger!” In the early 1890s, Helen made a huge leap forward in communication when she learned to “read” what people were saying by laying her fingertips on their lips as they formed words. With her left hand, she would feel the lip movements of her interlocutor; with her right hand, she would spell out her side of the conversation in one-handed manual language.

Annie Sullivan was the most important person in Helen’s life, but Alexander Graham Bell was a close second. He followed Helen’s intellectual development with deep interest, and was a constant source of support for both teacher and student. The affection was mutual. One of the first letters Helen wrote was addressed to “Dear Dr. Bell.” The letter demonstrates Helen’s brilliant intelligence: it was a remarkable achievement for a child who, only nine months earlier, had absolutely no vocabulary or linguistic ability. “I am glad to write you a letter. Father will send you picture. I and father and aunt did go to see you in Washington. I did play with your watch. I do love you.… I can write and spell and count. Good girl. …” Alec could scarcely believe his eyes when he read it: Helen proved all his theories about the capabilities of disabled children.

At one level, Alec’s interest in Helen was warm and paternal. As Annie Sullivan unlocked Helen’s intelligence, Alec took an almost personal pride in Helen’s achievements. He never personally taught her, but he learned the one-handed manual alphabet and Braille so that he could communicate with her. When he was with her, he treated her as first a child, and later as a young woman; he never patronized her or behaved, as so many of his contemporaries did, as though her disabilities made her less than human. He put a lot of effort into raising funds for her schooling. He also helped Helen herself financially on several occasions, sending her $400 when her father died in 1896, $100 toward a country holiday in 1899, and $194 in 1905 so that she could buy a wedding gift for Annie Sullivan.

Alec’s support for Helen Keller was unwavering, particularly during a nasty incident that occurred in 1891. Eleven-year-old Helen had written a short story, “The Frost King,” as a birthday present for Dr. Anagnos, principal of the Perkins Institution. Anagnos was so impressed with the story that he arranged for it to be published. But it turned out that Helen had unwittingly taken her inspiration from a story by Margaret Canby, published twenty years earlier, that had been read to her when she was eight. Mrs. Canby was not troubled by Helen’s inadvertent error: she sent Helen her love and called her version “a wonderful feat of memory.” But Anagnos and his colleagues at the Perkins Institution reacted as though the child had been a thief. A committee of trustees (“a collection of decayed turnips,” in Mark Twain’s phrase) cross-questioned a frightened and humiliated Helen about how she had developed the plot. Alec assured Helen that she had done nothing wrong: “[T]he child is quite incapable of falsehood about the matter,” he wrote to Mabel. Anagnos had behaved “in a most unjust and outrageous manner.” Alec suggested that “we all do what Helen did,” because “our most original compositions are composed exclusively of expressions derived from others.”

At another level, however, Alec saw Helen as “an interesting case”—a real asset to his crusade to improve education for the deaf and integrate them into the speaking world. In the late 1880s, he was very much caught up in a statistical study of deafness. He traveled to Augusta, Maine, to trace the history of a family called Lovejoy in which there were deaf members of every generation. He spent several weeks on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, where he had discovered an isolated community, with the glorious name Squibnocket, in which one-quarter of the population was deaf. He was able to track the course of deafness from an early settler on the island to Squibnocket’s living residents. He was also successful in persuading the U.S. Census Bureau to use the term “deaf” rather than “deaf-mute” on its 1890 census forms, so that more accurate figures on the incidence of deafness could be constructed.

Genealogies, census returns, family histories, and notebooks piled up in the Volta Laboratory in his father’s backyard in Georgetown. Alec divided the laboratory building into two sections, one for the scientific experiments for which it had originally been intended, and the second, to be known as the Volta Bureau, for “the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf.” (He reminded his assistant, John Hitz, that the phrase “increase and diffusion” was the kind of language that all great research institutions, such as the Smithsonian, had in their charters.) He accepted every invitation to speak about deafness or to visit schools for the deaf, long after he had given up speaking about the invention of the telephone. “I never knew him to refuse to lecture for the benefit of the deaf, or on anything related to the deaf,” his butler, Charles Thompson, recalled after his death. “There certainly was a tender chord in Mr. Bell’s heart for the deaf people of the human race. He seemed never so happy as when in company with the men and women identified with the teaching and training of the deaf.” And he never stopped campaigning for education in lip-reading rather than sign language, so that the deaf would not, as he saw it, be marginalized into their own language ghetto.

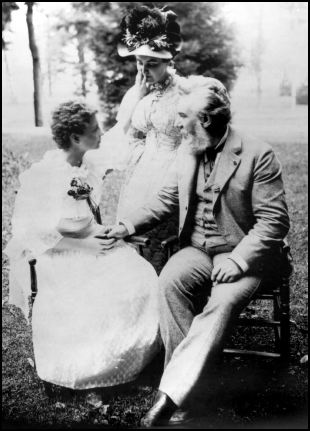

Helen Keller (left) with Annie Sullivan and Alexander Graham Bell.

Helen Keller was a wonderful figurehead for Alec’s campaign to raise awareness of the causes and consequences of deafness. The entrepreneurial spirit that was so absent in Alec’s scientific work blossomed in his efforts on behalf of the hearing-impaired. He did not hesitate to feed the public hunger for information about Helen by talking about her and Annie whenever opportunity arose. As early as 1888, he had given a copy of one of Helen’s letters and a photograph of her to a New York newspaper, and this made the eight-year-old a national celebrity. “The public have already become interested in Helen Keller,” he wrote in 1891, “and through her, may perhaps be led to take an interest in the more general subject of the Education of the Deaf.” While others described Annie Sullivan’s success with Helen as “a miracle,” Alec insisted that it was the product of educational method—of the way Annie constantly spelled out idiomatic English into Helen’s hand, allowing the child to learn meanings from the context.

When Helen was only twelve, Alec introduced her to his friends at one of his Wednesday-evening get-togethers. Helen sat in the middle of the erudite gathering, which included Professor Newcomb, Professor Langley, Gallaudet, and Alec’s father-in-law, Gardiner Hubbard. Despite being treated as a scientific specimen (Alec recorded that she was grilled on “the rotundity of the earth [and] her conception of geometrical relations”), the self-possessed youngster charmed her cigar-puffing audience. Her piéce de résistance came when she stood up, smoothed her skirts, and recited, in her strangely nasal tones, a poem familiar to all those present: Longfellow’s “Psalm of Life.” How could such an eminent assembly resist such lines as