Reluctant Genius (33 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

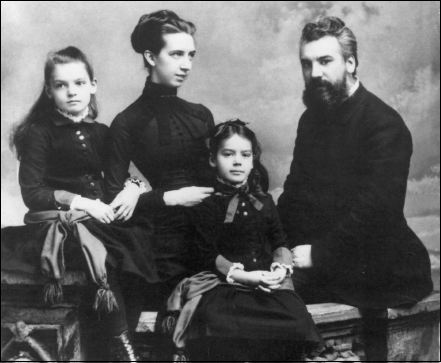

Mabel and Alec with their daughters Elsie (left) and Daisy in 1885.

The most difficult blow for Mabel came on November 17, 1883. She was seven months pregnant, her two little girls both had bad colds, and Alec had disappeared to a meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in Hartford, Connecticut. She began to feel ill, but the doctor reassured her it was just a cold and told her to stay out of drafts. In the middle of the night, a painful cramp awoke and her, and she realized with horror that she had begun contractions. With only Sister and a neighbor in attendance, she gave birth prematurely to another boy. “Poor little one,” she recorded sadly in her journal. “It was so pretty and struggled so hard to live, opened his eyes once or twice to the world and then passed away.”

Alec arrived home three hours later. He was saddened by the baby’s death, but he was particularly upset because he knew how much Mabel longed for a son and he did not know how to comfort her. He berated himself so vehemently for once again being away from home during such a crisis that Mabel had to dry her own tears and look after him. He would brood for years on his lost sons, his helplessness in the face of their deaths, and Mabel’s sorrow. “My true sweet wife,” he wrote in December 1885, “nothing will ever comfort me for the loss of these two babes for I feel at heart that

I

was the cause

… when death came and robbed us of the little ones we wanted so much, you forgot your own suffering to try and comfort me.” Two years later, the sight of Mabel cradling a doll in her arms (during a sitting with a portrait painter) prompted him to write, “I love you very much my darling little wife, and wish indeed you could be blessed as you desire.”

The Bells named their second son Robert. Mabel had little chance to recover her usual stoicism in 1883 before more family tragedies struck. Her brother-in-law Maurice Grossman died the following year, aged forty-one, of a liver tumor. Within a year, in 1885, her sister Roberta, wife of Alec’s cousin Charlie Bell, died in childbirth, leaving two little girls, Helen and Gracie. Meanwhile, Sister, Maurice Grossman’s widow, was fighting a losing battle with tuberculosis, from which she had suffered for twenty years. She eventually died in 1886, leaving her parents to raise the Grossmans’ only child, a daughter nicknamed Gypsy. The Hubbard-Bell clan now appeared much more fragile than it had at the start of the decade. Reflecting on the loss of her exuberant Hungarian brother-in-law, Maurice, Mabel noted how sadness had subdued her family: “We seem such a quite ordinary family now. Alec is a man out of the ordinary certainly but he is quieter in general life. He never shocks and takes away our pride with his overflowing spirits and utter disregard of conventionalities as Maurice sometimes did. We are all so quiet-mannered and self-restrained.”

The emotional stamina she had acquired as a child, alone in the school for the deaf in Vienna, gave Mabel reserves of strength with which to deal with death and with dashed hopes. But in Alec, stress induced all of his old hypochondria and feelings of panic. Writing from Boston in 1882, during another telephone patent hearing, he begged Mabel to join him: “I feel very unhappy and anxious about myself…going over old telephonic experiments excites me so much that I cannot sleep.” He complained constantly of chest pains: “When I feel badly now I find that my heart gives two beats then a stop. … I feel that the only chance of my getting over this heart-trouble is that

you should not leave me.”

Even when things were going well, such as at a scientific meeting in Philadelphia in September 1884, the heat often prostrated him. “All my spirit taken out of me,” he reported home. “My whole body and arms completely covered by heat eruption. The bath-tub my only refuge.” He traveled incessantly, visiting schools that taught lip-reading and lobbying state governments for day schools that taught either the oral method or a mix of signing and lip-reading, rather than boarding schools that taught only sign language. He complained nonstop in letters home. “I am tired out and going to bed,” he wrote Mabel from Chicago in 1885. “Even my hand refuses to write properly—feels inclined to cramp. Think I must have caught cold as my head feels full.”

The lowest point of Alexander Graham Bell’s life came in the fall of 1885. Against the backdrop of the loss of two sons, his wife’s grief, and his own frustration in the laboratory came news that the Pan-Electric Telephone Company had persuaded the U.S. government to file suit against the Bell patents. New York newspapers ran editorials suggesting that the Bell patent had been won by dishonesty and that Alec himself was a charlatan. For a man as temperamental and intense as Alec, this was devastating.

Mabel, still recovering from her sister Roberta’s death and worried about Sister’s failing health, could see her husband’s despair. He could not concentrate on any of his projects. He could barely play with his daughters. His thick hair and bushy beard, once so jet black, were flecked with gray, and he complained regularly of indigestion and back pain. He decided to close the little school he had founded for deaf children on Washington’s 16th Street, behind his Rhode Island Avenue mansion. After he announced his decision to teachers and parents and exchanged tearful farewells, he “came home to spend the afternoon, as he had spent the morning, on the sofa with a splitting headache and a heartache harder to bear,” Mabel noted in her journal. He told his wife that he felt his life had been “shipwrecked,” and begged her to travel with him to Boston for the next round of telephone hearings. With a characteristic touch of melodrama in his appeal, he told Mabel that he needed her to “keep him from an accident,” because, as she noted in her journal, he “feels as if I am all he has left.”

But Mabel was not all that Alexander Graham Bell had left. He was young and rich, and he retained an insatiable scientific curiosity. And by the time the Pan-Electric suit arrived in court, he and Mabel had also discovered a haven thousands of miles away from the heat and hurly-burly of Washington, a place that would be their refuge for the next thirty-seven years.

Chapter 13

A

TLANTIC

A

DVENTURES

1885–1887

The Bras d’Or is the most beautiful salt-water lake I have ever seen … the afternoon sun shining on it, softening the outlines of its embracing hills, casting a shadow from its wooded islands … here was an enchanting vision … We came into a straggling village [and] stopped at the door of a very un-hotel-like appearing hotel [the Telegraph House]. It had in front a flower garden; it was blazing with welcome lights; it opened hospitable doors … and we enjoyed the luxury of spacious rooms, an abundant supper, and a friendly welcome…. The reader probably cannot appreciate the delicious sense of rest and of achievement which we enjoyed in this tidy inn, nor share the anticipations of undisturbed, luxurious sleep, in which we indulged as we sat upon the upper balcony after supper, and saw the moon rise over the glistening Bras d’Or.

O

nce Alec had read this idyllic description of a tiny village in a remote eastern corner of North America, he couldn’t get it out of his mind. The book in which it appeared was

Baddeck, and That Sort of Thing: Notes of a Sunny Fortnight in the Provinces,

first published in 1874 and written by Charles Dudley Warner, a Connecticut resident who was editor of the

Hartford Courant.

He was a neighbor of Sam Clemens (Mark Twain), with whom he co-wrote a book with the resonant title

The Gilded Age.

Warner was a frequent visitor to Boston, and Alec and Mabel used to see his spare, genial figure pottering down Brattle Street when he came to visit his Cambridge friends, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Professor Charles Eliot Norton. A friendly encounter with the well-known editor prompted Alec to read his description of a journey through the Atlantic provinces of Canada. Warner had traveled through Nova Scotia and crossed the Strait of Canso to Cape Breton Island, an isolated region populated by Gaelic-speaking (and, in Warner’s gently satirical view, quaint) Scots. Warner and his traveling companion had taken nearly a week, by train, steamer, and horse-drawn cart, to reach the charming village of Baddeck from Boston. Alec read Warner’s gushing prose some time in the mid-1880s, at a point in his own life when he was oppressed by greedy American litigants, family tragedy, and the muggy heat of Washington summers. He found Warner’s hyperbole and the promise of seclusion and “undisturbed, luxurious sleep” irresistible.

Earlier in the decade, the Bells had spent summers on Massachusetts or Rhode Island beaches or in the mountains of western Maryland, but they had never found a summer property to which they felt drawn back each year. By 1885, they were eager to go farther afield. Alec’s father, Melville, was now sixty-six and had decided he wanted to make a sentimental journey to Newfoundland, the British island colony off Canada’s east coast where he had spent four bracing years as a young man in search of better health. Eliza, now seventy-six and lame as well as deaf, had no interest in any adventures, so Melville, who was still inclined to treat his son as if he were an unreliable eighteen-year-old, decided it would be good for Alec, Mabel, and their daughters to explore North America’s east coast with him. He found an unlikely ally in Gardiner Hubbard, who had sunk a lot of money into the Caledonia coal mines at Glace Bay, on the eastern tip of Cape Breton Island. If local legend is to be believed, Gardiner had even persuaded his Cambridge neighbor, the poet Longfellow, to invest alongside him. The Caledonia mines had been operating for nearly half a century, and Gardiner wanted his son-in-law to take a look at them. Once Alec had read Warner’s euphoric description of a tidy inn overlooking the glistening Bras d’Or Lake, the expedition came together.

So in late August 1885, Alec, Mabel, their two little girls, Melville, and a nursemaid called Nellie, carrying a mountain of bags, steamer trunks, and other luggage, took a steamer from Boston to Halifax, then a train from Halifax via Truro to the Strait of Canso (the narrow channel that separates mainland Nova Scotia from Cape Breton). There they boarded the S.S.

Marion,

a paddle steamer that took them through the narrow southern opening into St. Peter’s Inlet and Bras d’Or Lake. Mabel sat on the deck, spellbound by her first sight of one of the largest saltwater lakes in the world. Seventy miles long and ten to twenty miles wide, Bras d’Or Lake covers four hundred square miles in area and has over a thousand miles of interior coastline, bays, and channels. It is almost two lakes, as its eastern and western shorelines nearly touch halfway up its length, at a slender channel called the Barra Strait.

Bras d’Or Lake is the center of an idiosyncratic North American island community initially composed of Catholic Scots who were driven out of the Scottish Highlands by famine, rising rents, and land enclosures from the late eighteenth century onward. Attracted by free land and salmon-rich rivers, they weathered the harsh winters and imported a tradition of ceilidhs (festivals) and fiddle-playing. In 1802, when Presbyterian Scots had joined the exodus from their native land, the island boasted 2,513 inhabitants. By the time the Bells arrived, over eighty years later, the population had soared to over 80,000. What made this particular corner of the British Empire unique was that nearly all Cape Breton immigrants came from the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and islands of Scotland. And geography dictated that they remained undiluted. With no railroad until the 1890s and no causeway to the rest of Nova Scotia and Canada until the mid-twentieth century, the island nurtured a deeply conservative society, clinging to its old clan structure, its belief in fairies, and an addiction to “toddy.” A substantial proportion of its population didn’t speak English. Long-established Gaelic customs, such as “waulking” or milling the cloth, were occasions for singing old Gaelic songs and composing new ones. Cape Breton was, in fact, a more deeply Gaelic society and culture than the one that many of its members, and certainly Alec Bell himself, had left behind in Scotland.

Mabel had little inkling of this as she sat on the

Marion’s

deck. She was captivated by the dazzlingly white little lighthouses on the shoreline, punctuating the dark backcloth of spruce, fir, and pine. “It is perfectly lovely here, the archipelago of islands and the mainland with its steep hillsides sloping down into the water,” she told her mother. “I do not see that there is anything more beautiful on the Corniche between Menton and Nice.” Alec and Melville listened with amusement to the Gaelic (which neither of them spoke) and Scots accents of their kilted and cloth-capped fellow passengers. “Everybody here is Mac something,” Mabel noted.

The Bell party stopped only briefly at Baddeck, to see whether the Telegraph House lived up to Warner’s description (it did). However, the overnight visit did allow Alec to discover that a telephone line ran between the local general store and the local newspaper, the

Cape Breton Island Reporter.

According to Baddeck folklore, Alec was walking past the newspaper office’s plate glass window when he caught sight of the newspaper’s editor, Arthur McCurdy, trying to make the wall-mounted phone work. The next thing that the young editor knew, a tall, beefy man with bushy black hair and whiskers had entered his office to ask him what he was doing. McCurdy explained that he was trying, without success, to fix the phone. The stranger unscrewed the end of the earpiece, removed the diaphragm, brushed a small fly away, replaced the diaphragm, screwed the end back on, and said, “I think now you will find it working.” McCurdy tried the phone and immediately got through to the store, which was run by his father. Shaking the strangers hand, he asked him, “How did you happen to know about this?” The stranger smiled back: “Because I am the inventor of that instrument.”