Reluctant Genius (34 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

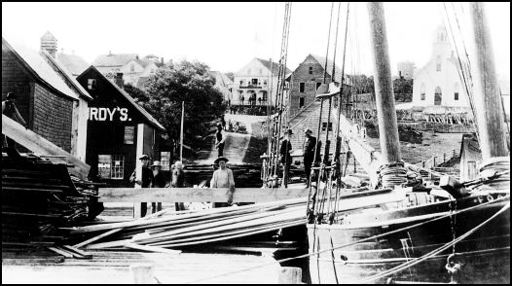

The crowded wharf at Baddeck.

The Bells made an even briefer stop at Glace Bay, to check out the Caledonia mines. But Melville Bell was eager to reach Newfoundland, and hustled everybody back to Halifax and onto the S.S.

Hanoverian,

a steamer bound for St. John’s, Newfoundland, under the command of a Captain Thompson. There were 280 passengers aboard, 40 of whom (including the Bells) were saloon class and the rest in steerage, plus a cargo of canned meat, tobacco, and pork.

The Bells had made several transatlantic voyages without incident by now, and as dusk fell and the

Hanoverian

weighed anchor, they settled happily in their saloon cabins. But a thick fog rolled in while the steamship made its way up the coast of Nova Scotia toward Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula. The captain insisted he knew exactly where he was, and despite the fog (now as dense as pea soup) and the concern expressed by some passengers, he refused to check his position with a couple of fishermen whose boat appeared out of the fog and who waved vigorously at them. In the laconic account that appeared in the St. John’s newspaper, the

Evening Telegram,

“Expecting to be around Cape Race, he took Cape Mutton to be Cape Ballard.” It was a fatal miscalculation: the

Hanoverian

had not yet rounded the vicious rocks of Cape Race, at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula. Just before ten o’clock on the third morning, all hell broke loose. Mabel felt the boat come to a shuddering, grating halt; Alec heard panicky shouts from the crew The steamer had gone aground on a reef off Portugal Cove South. Melville Bell came roaring out of his cabin, Nellie the nursemaid fell to her knees and started praying, and Mabel quickly dressed her little girls in their warmest clothes. Alec was already on deck, trying to find out the extent of the damage.

Captain Thompson, according to the

Evening Telegram,

did not rise to the occasion. When two “respectable planters [settlers] … launched their skiffs and offered assistance … the captain declined, and referred to them as savages, this unwarranted expression coupled with a strong seaman’s adjective.” But Captain Thompson had his reasons for such behavior: Newfoundlanders from Cape Race had a fearsome reputation as wreckers. And Captain Thompson’s situation was not eased by the conduct of his own crew, who (again according to the admittedly partial

Evening Telegram)

“behaved disgracefully, exhibiting incompetency, drunkenness and insubordination.”

Luckily, among the

Hanoverian’s

passengers were some British sailors, who soon started lowering lifeboats and organizing people onto them. Meanwhile, Alec had returned to the cabin to tell Mabel—who could not hear the shouted orders to leave the ship—what was going on. Then he took five-year-old Daisy in his arms, grabbed seven-year-old Elsie’s hand, and chivied his wife and father ahead of him. Daisy would never forget watching her Grandfather Bell clamber laboriously down a rope into the dinghy while a sailor called out, “Here! Wait for this big fat man!” Despite the panic around her, Mabel displayed her usual sangfroid as her husband got them all seated in a lifeboat. But as she admitted to her mother in a letter, “Just fancy! Alec left his valise with his precious deaf-mute books in his cabin. He did not forget them, but actually preferred leaving them to run their chance to letting his wife go on the boat without him. I felt quite elated!”

The passengers and the crew of the S.S.

Hanoverian

all reached the little village of Portugal Cove South safely. Things didn’t go so well after that. The

Evening Telegram’s

correspondent claimed that everyone was “comfortably sheltered in the houses of the hospitable fishermen in the Cove,” but that wasn’t Mabel’s experience. “If the wreck was a gentle one,” she reported to her mother, “the rescue was a hard one badly managed or rather not managed at all. A more solid inhospitable set of people than these of Portugal Cove I hope never to see. Not a thing would they do except for pay and that as badly and grudgingly as possible.” Since there was no road along the rocky coast to St. John’s, the passengers had to wait for the British naval vessel H.M.S.

Tenedos

to pick them up. The following day, the seas were too rough for open boats to ferry them to the British vessel, which steamed away to Trepassey, a village eight miles along the coast with a better harbor. The

Hanoverian’s

passengers were told to make their own way there overland. As they straggled down the rutted coastal path, past peat bogs and rock fences, they saw coming toward them a menacing spectacle: bands of men with boat hooks on their shoulders and knives in their belts—the ill-famed wreckers, looking for salvage, or, as Mabel put it, “vultures intent on their prey.”

Alec proved a tower of strength in the melee. He paid for tea and coffee to be served to the bedraggled passengers, then strode off beyond Trepassey to find some means of transport for children, the elderly, and the sick. He returned with horse-drawn wagons, brought his own family to a Trepassey inn, and installed them in a private set of rooms there. Mabel wrote admiringly of his efforts to her mother but noted wryly, “Tomorrow I fancy the collapse will come, but he feels happy for he thinks yesterday has proved that he has not heart disease.”

The

Hanoverian’s

passengers finally sailed off to St. John’s aboard the

Tenedos,

with the ship’s captain carefully taking depth soundings throughout the voyage up the Avalon Peninsula’s craggy shores. By now, the calamity had become an adventure. A band played in the ship’s salon for the rescued passengers. The British naval officers charmed Mabel and had an endless supply of candy for Elsie and Daisy. A couple of days later, the vessel sailed through the Narrows into St. John’s harbor, and nosed its way between the numerous tall-masted schooners, bobbing up and down at their moorings, toward one of the narrow finger wharves that jutted into the harbor waters. “We found all St. John’s on the wharf,” Mabel reported to her mother, “waiting to see the shipwrecked passengers land, but they must have been disappointed for [although] nearly every one owned only the clothes they stood up in, they looked very respectable—Alec especially, who is fast developing into a dandy in his old age.” Most of those on the wharf were there to greet the wife and daughter of the bishop of Nova Scotia, en route to join the bishop in England. There was no mention in the local newspaper that the American millionaire Alexander Graham Bell, famous inventor of the telephone, was among the shipwrecked, since the party was listed on the ship’s manifest as “Mrs. G. Bell, two children and maidservant… Messrs. Bell, G. Bell” from Halifax. But Alec was delighted to find a welcoming party of telegraph men, who had booked rooms for his entourage at the posh new Atlantic Hotel, on Duckworth Street. While Mabel sorted out their soggy luggage (“I shall save my underclothing but everything that won’t stand thorough cleaning is ruined”), Melville Bell went off to find the Macphersons, a family from Glasgow who had befriended him in Newfoundland half a century earlier.

Alec emerged as leader and advocate for all the

Hanoverian’s

passengers. The sight of her terminally undomesticated husband being consulted by so many women amused Mabel: “All the ladies depend on Alec for everything. He must advise about their trunks, about drying their clothes, prayer books and photographs, it is really absurd.” He began a campaign to find funds and clothing for their more destitute fellow passengers. “We hope that the people of St. John’s will make ample amends for the inhospitality of those of Portugal Cove,” commented his wife.

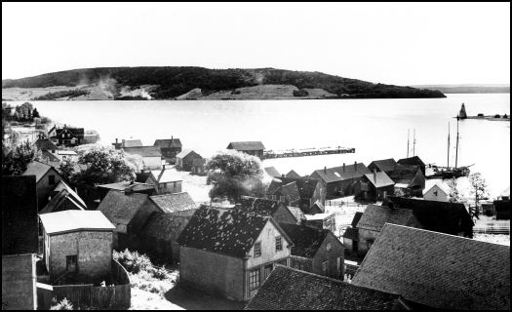

The view from Baddeck of Red Head, which Alec would rename Beinn Bhreagh.

The Bells remained in St. John’s for about a week. They were fascinated by its dramatic beauty and its idiosyncrasies; since much of the population was illiterate, the stores on Water Street and Duckworth Street followed the age-old practice of advertising their contents by hanging out signs such as a giant pocket watch for a jeweler, a boot for a shoe mender, and a red and white pole for a barber. On the fish-drying sheds, noted Mabel in her journal, “lie the whitening carcasses of more fish than I ever saw in my life before.” But Newfoundland was too isolated, too harsh, too

Irish;

Alec hankered after the gentler Scottish charms of Cape Breton. So the party boarded a ship in St. John s harbor, bound for Nova Scotia.

Three days later, they were steaming back across the Bras d’Or Lake to Baddeck and the spool beds, old-fashioned crockery, and creaking stairs of the Telegraph House. Years later, Maud Dunlop, daughter of the hotel’s owner, recalled seeing the family on their return in September 1885: “Mrs. Bell, at this time in her late twenties, [was] a slender person with the gentlest manners, her sweet sympathetic face framed in the most beautiful soft brown hair. She and her dark-eyed little girls made a lovely picture; they were most devoted to her…. I can see her [now], sitting on the upper verandah reading aloud to them while their governess was out.”

In the soft September sunshine, with puffy white clouds reflected in the lake’s calm water, Baddeck was as tranquil and rejuvenating as Charles Dudley Warner had promised. During the next few weeks, Alec and Mabel walked, drove, and explored. They swam in the invigorating salt water; they rowed along the rocky shore. They sailed up the bay, and had to be rescued by a thoughtful Cape Bretoner when the breeze died. At dawn, they watched the sun rise behind the Kempt Head headland opposite the village, and in the evening they watched its last scarlet rays fall on Red Head, a headland just beyond Baddeck harbor. Alec luxuriated in the fresh breezes off the water and played chess with Arthur McCurdy, the local newspaperman whom he had met a month earlier. Mabel savored the precious family intimacy. “I think we would be content to stay here many weeks just enjoying the lights and shade on all the hills and isles and lakes,” she wrote in her journal. “I cannot see why C. D. Warner should be possessed of such a mad desire to come here that he must travel so uncomfortably day and night … to spend two days here. No wonder the good people here took him for insane.” By late September, when it was time for the Bells to return to Washington, Alec had decided they must come back the following year and find a cottage by a running brook where they and their children might enjoy simple pleasures, far beyond the reach of the Pan-Electric Telephone Company’s lawyers. Baddeck had revived the dream that had lain dormant since he and Mabel had spent their romantic (albeit uncomfortable) week in the cottage in Covesea, Scotland, just after their marriage.

Sure enough, the Bells were back in Cape Breton in July 1886. Arthur McCurdy had found a property for them to rent: a bare four-room cottage (“at best it is a regular shanty,” according to Mabel) a mile outside the village, overlooking Baddeck Bay. They named the cottage Crescent Grove, and these American millionaires set about devising ways to improve on its scarce furnishings. A wooden armchair, a box, and a hay-filled mattress became a chaise lounge; a hammock was improvised from barrel staves held together with rope; fabric flung over boxes artfully transformed them into shelves and tables. It was all very make-do-and-mend compared to the splendors of Washington, but Baddeck fulfilled the fantasy shared by Alec and Mabel that they wanted only “the simple life” and that their wealth and privilege were of no consequence to them. (Nevertheless, Alec was soon the proud owner of a stylish steam launch, which was certainly beyond the means of most year-round Baddeck residents.) “Alec’s patience with all his following of wife, children, nurse and two dogs, butterfly net, lunch basket etc. is something wonderful,” Mabel wrote to her mother-in-law.

Mabel had decided that it was stupid for her little girls to be climbing trees and running through the long grass in petticoats and skirts. So in Halifax, en route to Cape Breton, she had stopped at a men’s store and ordered trousers for boys “about the same size as my daughters.” (An open admission that she intended dressing her girls in boys’ outfits would have triggered shock and horror.) Once in Baddeck, Elsie and Daisy climbed trees, acquired a pet lamb called Minnie, and lost their hair ribbons. Mabel made raspberry jam and blackberry jelly and watched the nursemaid Nellie teach their newly acquired cook some fancy dishes. Alec pitched a tent on the lawn and insisted on spending the night there. The Bells were so determined to achieve simplicity that they acquired a cow, “Miss Miggs,” and a wooden churn so they could make their own butter: “We all worked, Alec, the children and I, and after a long hard bout we had the delight of seeing butter form. It did look like tightly scrambled eggs at first but Nellie … soon brought it into shape…. But we found the churning process less delightful in practice than in theory and Alec is trying to invent a windmill to do our churning for us.” In the meantime, Elsie, Daisy, and Mabel churned while Alec played “Onward Christian Soldiers” on a portable organ to cheer them on.