Reluctant Genius (32 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Mabel urged Alec to compensate for her handicap. “Do take care of your precious health,” she instructed him, “for the sake of your wife and the helpless little ones who have only half a mother. They need you more and more every day.” She was quick to correct him when he referred in a letter to “your children” :“our, not

yours,”

she replied crisply. And she constantly reminded him that “they so need their mother and their father’s eye … when their characters are developing, and little faults springing up, that if not checked may grow serious.”

Newborn Edward’s death increased Mabel’s maternal insecurity. While Alec, a self-declared atheist, chose to see the baby’s death as a physiological event that could have been prevented by a better medical device, Mabel sought answers within her Christian faith. She wondered if God was chastising her. One day, when Elsie was being naughty, Mabel withheld candy from her and explained that she was punishing Elsie as God had punished her. She told the little girl, she explained in a letter to Alec, “He had promised me a baby if I would be careful, but I had not been, and He took the little one from me.” When Alec tried to brush off such thoughts with cold hard reason, he made his wife even more unhappy. In the end he could only write, “I would not for the world have my skepticism destroy your faith. You do me injustice to suppose that I smile at your ideas and only ‘pity your credulity.’”

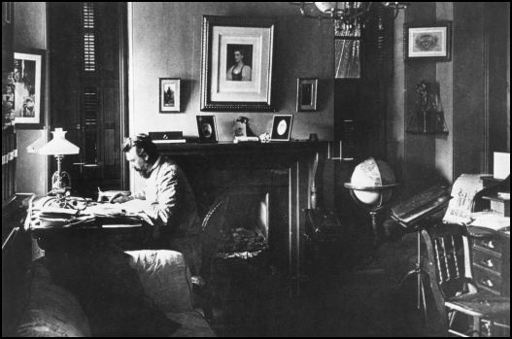

Alec rarely left his Washington study before midnight.

When the Bells were in Washington, Alec was typical of his era in being a distant father—frequently absent, and not particularly involved with his children when he was at home. There were always nursemaids, servants, sisters, or female cousins around to keep Mabel company and help mind the children. But on the lengthy journeys by steamer, train, and carriage through Europe in 1881-1882, Mabel, Elsie, and Daisy saw far more of him. Not that he got involved in all their activities—in Paris, Mabel found his secretary, William Johnson, a better shopping companion than her husband. “If I took Alec,” she told her mother, “he would be sure to have a bad attack of heart trouble in the first shop and make me buy all I didn’t want.” He was far happier, his wife reported, hunting for caterpillars in the Bois de Boulogne, “as he has an idea that he can find a method of preventing them from climbing trees!” He also complicated their ménage by acquiring two little monkeys, which wrought expensive havoc in their suite of rooms in the Hotel Metropolitan, tearing at the wallpaper, pulling down curtains, and chewing through bell cords. Nevertheless, Alec was there to horseplay in hotel rooms with his little girls and to carry Daisy on his shoulders when they went sightseeing. There is a refreshingly modern ring to Alec’s attitude to parenthood during an era when most affluent parents regarded themselves first and foremost as figures of authority. He believed that “play is Nature’s method of educating a child” and that a parent’s duty is to “aid Nature in the development of her plan.”

The renewed closeness helped Mabel and Alec recover from the grief of Edward’s death. When Mabel heard that her sister Berta Bell had given birth to a daughter, she wrote to her mother, “I begin to envy … Berta, and think it almost time I had a wee baby too. … Do you suppose I ever shall?” Two weeks later, she heard that her sister Gertrude Grossman had also had a safe delivery of her first child. “Of course,” she wrote, “I am very much disappointed and sorry for you and Papa and Maurice [at the arrival of yet another girl] though if it had been a boy I could not have helped feeling just a tiny little bit jealous when I thought of my own little one.” Such thoughts reopened old wounds: “I would like a boy Oh so much.” But Mabel’s sturdy good sense had reasserted herself, and she determined to enjoy all that Paris could offer, whatever her husband’s eccentricities. “I am having a calling dress of ruby silk and velvet for next winter made at Worth’s. … I feel like having the name pasted on it in a prominent position, I believe in getting my money’s worth and what’s the use of a dress from Worth’s if no one knows it.” Within a few days she was writing to her mother, “No little boy can be half as nice as little girls. My own little ones I think grow nicer every day.”

In June 1882, the Bell family returned to the United States and purchased their first permanent home in Washington: 1500 Rhode Island Avenue, on Scott Circle. It was an immensely grand three-story, redbrick mansion, with a billiard room, a library, and a music room containing a grand piano for Alec. It was lit by electricity throughout, and the extensive servants’ quarters enjoyed a steam-heating system. The house was so splendid that the Bells did not at first realize that it was badly built, with inadequate sewage pipes that put them at risk for typhoid—the scourge of nineteenth-century Washington. Even the stables had pine paneling. They also had some unusual occupants: alongside the horse there was a menagerie of cats and monkeys. The cats were all white with blue eyes—Charles Darwin had asserted that cats with these characteristics were always deaf, and Alec wanted to see if he was right. The monkeys were some of Alec’s favorite pets, but Mabel wouldn’t let them in the house because the servants objected to cleaning up after them, and Perrin, the coachman, complained that “Mr. Bell’s monkeys and white cats were driving the horse out.”

Thanks to his fame and to his efforts on behalf of President Garfield, Alec’s black eyes and bushy beard were well known by now in Washington. Few realized that he remained a British citizen: he had not pursued the application he made for naturalization papers in 1874, because Gardiner Hubbard had taken on the job of submitting the patent applications. But he had now lived in the United States for over a decade, his own parents were also living here, and he was the father of two small Americans. He decided that it was time to declare his loyalty and become a full-fledged citizen of his adopted country. On November 10, 1882, Alec marched off down Rhode Island Avenue toward the center of the city, and entered the office of a local judge. There, with his right hand on a bible and his left hand making a salute in the air, he took the oath of allegiance to the United States. Mabel probably did not accompany him, but she certainly heard all about it. She complained to friends that her husband was irritatingly proud of his new status. “Yes!” he would proclaim to her. “You are a citizen because you can’t help it—you were born one, but I

chose

to be one!”

While Mabel organized the new house, Alec plunged back into the work of the Volta Laboratory. Before his departure for Europe, he had been working with Sumner Tainter and yet another Bell relative—David Bell’s elder brother, Chichester (known as Chester)—on improvements to Thomas Edison’s sound-recording design, which he had named the “phonograph.” Edison’s invention, patented in 1877, recorded sound on cylinders covered in metal foil, but it was useless. The cylinders were scratchy, brittle, and unreliable, producing speech or music that was recognizable but not clear. Alec, along with Tainter and Chester Bell, was looking for ways to make the recordings clearly audible and sturdy. In Alec s absence, Tainter and Bell had experimented with different techniques and materials for what they preferred to call the “graphophone.” After trying several different systems of recording, including jets of different substances (compressed air, paraffin, and maple syrup), and different materials on which to record, including wax-coated paper, cylinders, and disks, they had come up with a cylinder with a wax surface on which a sharp stylus incised the sound. Then they moved on to flat wax disks, with the idea that verbal messages incised onto them could be sent through the mail, like written letters. Once back in Washington, Alec spent almost every day in the laboratory, discussing his colleagues’ advances and making suggestions on different approaches. His participation justified the inclusion of his name on some of the Volta Laboratory patents for the phonograph. (Thomas Edison would have to purchase those patents when he put the phonograph into commercial production in the early 1890s.) But he also worked on his other projects, including the vacuum jacket and induction balance. And he was increasingly drawn back into a world in which he continued to feel a strong sense of mission—the world of the deaf.

The Massachusetts State Board of Health had asked Bell to undertake a statistical study of hereditary deafness, and as he plodded through pages of census data, he became fascinated by the laws of genetic inheritance. In England, Darwin’s cousin Sir Francis Galton was analyzing the pedigrees of famous men, and Alec was infected by the rising interest in the study of human heredity. Deaf parents, he found, were more likely than the population at large to have deaf children. Moreover, deaf people were more likely to marry deaf partners.

This research led him, in November 1883, to submit a paper to the National Academy of Sciences under the unfortunate title, “Memoir upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race.” In this paper, he discussed his research on family patterns of deafness. He suggested that a congenitally deaf couple should be warned of the risk of having deaf children, and he also urged that deaf individuals should be given more opportunity to form friendships (that might lead to marriage) with hearing persons, in day schools. He even raised the possibility that “intermarriage between deaf-mutes might be forbidden by legislative enactment,” although he went on to dismiss such legislation on the grounds that “interference with marriage might only prompt immorality.” But his paper triggered a storm. The

New York Times

gave its report the headline, “A Deaf-Mute Community, Prof. Bell Suggests Legislation by Congress.” And the deaf community was outraged by the paper’s title, since it seemed to imply they belonged to an inferior species.

To a modern reader, who knows to what abuses the science of eugenics would lead, the pamphlet has a chilling ring. But Alexander Graham Bell was only one of many nineteenth-century men of science who pursued ideas that today seem naive or malevolent. There was as much bad science as good science around. President Garfield’s death, for instance, had resulted from a belief in the miasma theory of disease—the assumption widespread during this period (Florence Nightingale was among its proponents) that infection was spread by “bad air.” It took American physicians years to accept the idea that germs caused infections and to adopt the practice of scrupulous cleanliness that had been advocated since the mid-1860s by Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister. Similarly, after Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, was hanged, his skull was carefully preserved so that another group of nineteenth-century quacks, the phrenologists, might compare its shape and bumps with those of other criminals. Phrenologists believed that the protuberances on the skull provided an accurate index of talents and abilities, such as benevolence or laziness.

Soon after the Bells moved to the house on Rhode Island Avenue, Alec opened a little private day school, on nearby 16th Street. He rented the ground floor to a local kindergarten, and then found a teacher for a class of six deaf children, aged between three and eight, on the second floor. At recess, all the children (including his own two daughters) played together, so that the deaf children might watch the hearing children speak during communal play. The parents of deaf children received instruction in Visible Speech to enable them to continue teaching their children at home.

Though Alec and Mabel loved one another deeply, the stresses on both of them kept mounting during these years. Alec felt strung out between the phonograph, his deaf studies, the little school, and the telephone litigation that periodically sparked commotions in the press about whether or not he was the “real” inventor. He frequently withdrew from family life and retreated to his study or the Volta Laboratory to read scientific journals. He often sat down at the piano and played to himself for half the night. “He played very dramatically, and it seems to me that he particularly liked big, stirring passionate things,” his daughter Daisy would recall after his death. “He played with his whole soul and his whole body too, and I liked the way the big curl on top of his head would wobble about.”

Meanwhile, Mabel resented how little she saw of her husband and how often he was too preoccupied to pay attention to their daughters. “It does feel awfully lonesome without you, my big burly husband,” she wrote to him. “When you are here you are the object around which all my life moves, and now you are away it feels empty and objectless.” Were all his activities really warranted, she asked? “Why was our wealth given us if not to give

you

time to make up to

your

children what they lose by their mothers loss?” After a family visit to her parents, who had now returned to Washington, she wrote despairingly in her journal, “Alec talked genealogy all the time. He thinks that in the course of a hundred years, material will be gathered through Genealogical Societies from which important deductions can be made affecting the human race. … I am afraid I am not particularly interested in investigations that can only be used a hundred years hence.”