Reluctant Genius (14 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Through April and May, there was no time for romantic daydreams. Alec toiled away, both in the Sanders home in Salem and in the Court Street attic in Boston, trying to put his multiple-telegraph equipment into commercially acceptable working order. He was frustrated by his lack of technical education in electricity, although he tried to reassure himself with the knowledge that “Morse conquered his electrical difficulties although he was only a painter, and I don’t intend to give in either till all is completed.” Each day, before striding off to fulfill his Boston University duties, he gave to the loyal Watson notebooks filled with sketches. Shortage of money and the problems of interference of frequencies and faulty transmitters bedeviled him, but he did not dare ask Gardiner Hubbard for a further investment. He was forced to borrow from Watson, whose weekly wage of $13.25 was just over half what Alec earned from his university duties. And though he knew that his backers wanted him to focus on the invention that might challenge the Western Union monopoly, his thoughts kept straying back to the electrical transmission of human speech. “In spite of my efforts to concentrate my thoughts upon multiple telegraphy,” he recalled later, “my mind was full of it.”

As summer approached, the temperature rose in the attic workshop, and blueprints, electromagnetic coils, tuning forks, and steel rods accumulated on the wooden workbench. Next to the attic’s grime-encrusted arched window, oblivious to the quiet hiss of an overhead gas lamp, Alec crouched over his latest prototype for the telegraph transmitter. He was trying to tune the receiver reeds. One minute he would summon Watson to help him fix a detail, the next he would send him to the next room to see if a receiver there was working. The breakthrough came on June 2, when the two men, sleeves rolled up and foreheads glistening in the oppressive heat, tested out a trio of transmitters and receivers. As Watson adjusted the spring of one of the receivers in the adjoining room, Alec realized that the corresponding transmitter in his laboratory had spontaneously begun to vibrate. He put his ear next to it, and heard a distinct “twang.” He dashed next door to see what Watson was doing to cause the vibration. Watson explained that he had plucked the spring. “Keep plucking it!” Alec snapped, as he returned to the laboratory.

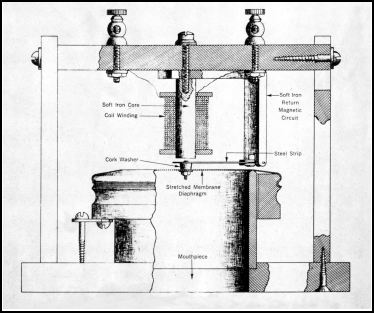

The first membrane diaphragm telephone, June 1875.

He had immediately grasped the import of that “twang” for the “speaking telegraph” that had continued to haunt his imagination. The plucked spring was inducing the wave-shaped current he had postulated the previous summer, in Brantford. During the intervening months he had been stymied in developing this intuition because he had believed that only a substantial continuous electric current, generated by an external battery, could convey the complex harmonics that constitute human speech. Now he realized that his assumption was wrong: a weak alternating current, induced by the vibrating spring, had transmitted a precise sound from one room to the next. As the spring vibrated, it changed the width of the air gap between the spring and the end of iron core of the electromagnet. Varying this air gap changed the magnetic field in the coil, which in turn induced an electric current that corresponded to the motion of the vibrating spring. Alec and Tom Watson worked far into the night, repeating the discovery with all the steel reeds and tuning forks that they could find. “Before we parted,” recalled Watson, “Bell sketched for me the first electric speaking telephone, beseeching me to do my utmost to have it ready to try the next evening.” With several refinements, these sketches were the designs for the instrument that would eventually become the first telephone.

That night, Bell wrote a quick note to Hubbard: “I have succeeded today in transmitting signals without any battery whatever!” and added that he thought this was a more important direction in which to proceed than the multiple telegraph. He wrote to his parents in a similar state of euphoria: “At last a means has been found which will render possible the transmission … of the human voice.” He told them he hoped to have an instrument “modelled after the human ear, by means of which I hope tomorrow (but I must confess with fear and partial distrust) to transmit a vocal sound. … I am like a man in a fog who is sure of his latitude and longitude. I know that I am close to the land for which I am bound and when the fog lifts I shall see it right before me.”

When Alec arrived at the Court Street workshop the following evening, Watson triumphantly produced the apparatus he had sweated over all day. The first telephone was a simple mechanism, consisting of a wooden frame on which was mounted one of Alec’s harmonic receivers—a tightly stretched parchment drumhead to the center of which was fastened the free end of the receiver reed. The new element was a mouthpiece arranged to direct the voice against the other side of the drumhead.

Alec connected this apparatus by wire to another harmonic receiver in the metalworking shop downstairs, now empty of the men who kept it buzzing all day. An early experiment seemed to fulfill his hopes: when Alec shouted into the first prototype transmitter, Watson came dashing upstairs to report he had heard his boss’s voice over the wire and could almost make out the words. But when the two men switched places and Watson spoke into the transmitter, Alec heard only a babble of unintelligible sounds. His heart sank. He leaned back in his chair, brooding on this frustration and realizing that he might have to spend hundreds more hours at his workbench doing what he least enjoyed—making laborious and minute adjustments to delicate membranes and lengths of wire.

Further discouragement came from Gardiner Hubbard, who arrived at Court Street to inspect the diaphragm device. As he climbed the grubby, narrow staircase to the attic in which Alec and Watson worked, he grunted with effort and disapproval. He was deeply in debt and badly needed a commercial success. Orton, of Western Union, had announced his conviction that Alec’s rival, Elisha Gray, would win the multiple-telegraph race. And, the irrepressible Thomas Edison was telling everybody within earshot that his breakthrough in multiple telegraphy was imminent. Hubbard was painfully aware of Orton’s personal vendetta against him since he had tried to challenge the Western Union monopoly in Washington the previous year, but he was also confident that Orton was too good a businessman not to grab the first commercially viable telegraph invention produced, whoever its inventor. Preoccupied with these concerns, Hubbard was visibly skeptical as he examined his protege’s vibrating diaphragm. “I am very much afraid,” he announced, “that Mr. Gray has anticipated you in your membrane attachment.” Alec could not convince him that it was anything more than a distraction from the more important pursuit of the multiple telegraph. Gardiner urged Alec to expend his energies on the multiplex telegraph.

That,

he declared, was the “ne plus ultra” of communication technology.

Alec was almost paralyzed with despair. For the previous year, he had been working night and day to fulfill his teaching obligations and pursue his research interests. His financial worries, the dripping heat of a Boston summer, and his frustrations with the telegraph experiments had already taken their toll. But now he suffered two further blows. First, Watson fell ill with typhoid, further impeding progress on either the harmonic telegraph or the telephone. And then Gardiner Hubbard casually mentioned that Mabel was leaving Cambridge in a couple of weeks and would be out of town for the entire summer.

The news of Mabel’s departure forced Alexander Graham Ball to confront the feelings he had repressed for months. The idea of Mabel spending weeks so far removed from Cambridge horrified him: he realized how much he had come to depend on their casual conversations, either in the Hubbards’ mansion or in his rooms on Beacon Street. He admitted to himself that, these days, he daydreamed for hours about a time when he might take that “fair young girl” into his arms, a time “when I should feel those soft white arms around my neck or dare to touch that glorious hair.” His emotions boiled over. He penned an anguished letter to his parents: “It is now more than a year ago since I first began to discover that my dear pupil,

Mabel Hubbard,

was making her way into my heart. … It has been my object up to the present time to conceal from her—from you—and from myself how deep has been the interest I have been taking in her welfare. I say this that you may understand that the sentiments so recently expressed to you on the subject of marriage were

true

when they were written.” The news that she was going on an extended visit to Nantucket, the idyllic island thirty miles off the south coast of Cape Cod, destroyed his self-imposed charade. “It was useless striving longer against Fate—I must either declare myself or lose her. I did not know what to do.”

So he declared himself, in a letter to Mabel’s mother. On June 24, 1875, three weeks after the coiled spring of the transmitter had uttered its fateful twang in his attic workshop, Alec sat at a desk in 292 Essex Street, the Sanderses’ Salem house, and stared at a blank sheet of paper. He dipped his pen’s metal nib into the ink and watched the liquid drip back into the inkwell. He scratched his beard nervously. His hand shook and his mind raced as he searched desperately for the right words. He had more than enough trouble expressing himself when he wrote accounts of scientific experiments; describing his own emotions was almost beyond him. Finally he began to write. But there would be many false starts and discarded drafts before he perfected his opening paragraphs:

Dear Mrs. Hubbard,

Pardon me for the liberty I take in addressing you at this time. I am in deep trouble, and can only go to you for advice.

I feel sure that whatever answer you may vouchsafe to this letter, your sympathies at all events will be with me.

I have discovered that my interest in my dear pupil, Mabel, has ripened into a far deeper feeling than that of mere friendship. In fact I know that I have learned to love her very sincerely. Could you suspect how desolate the announcement of her early departure from Cambridge has made me, you would indeed pity me.

Chapter 7

N

ANTUCKET

P

ASSION

1875

G

ertrude Hubbard sat down and reread Alec’s untidy scrawl, her eyes wide with astonishment. Then she stared out of the library window at the foxgloves, larkspurs, and bleeding hearts in her Brattle Street garden and considered her response. She had suspected that Alec was sweet on Mabel, but she had no idea that he harbored feelings of such intensity, such passion. She was suffused by a wave of protective feelings toward her seventeen-year-old daughter: Mabel might have the demeanor of a sophisticated Brahmin debutante, but Gertrude knew she was still young for her age and very dependent on her family. Although she had never been allowed to feel marginalized by her hearing loss, she was rarely alone among strangers. Away from Cambridge’s familiar turf, she was at risk—of runaway street vehicles, because she could not hear shouts of warning; of house fires, because she could not hear alarms.

The day before Alec’s letter arrived at Brattle Street, Gertrude Hubbard had invited him to listen to the speeches and watch the fireworks with her and her daughters at Harvard University’s GraduationDay festivities. Alec would be arriving any minute, anxious to hear Gertrude’s reaction to his declaration of love and to see Mabel before her departure. “It is my desire,” his letter had continued, “to let her know now how dear she has become to me, and to ascertain from her own lips what her feeling towards me may be. Of course I cannot tell what favour I may meet with in her eyes. But this I do know, that if devotion on my part can make her life any the happier, I am ready and willing to give my whole heart to her.”

Alec ended his letter of entreaty to Gertrude Hubbard, “I am willing to be guided entirely by your advice, for I know that a mother’s love will surely decide for the best interests of her child.” But Gertrude was too astute a woman to believe that someone as highstrung as Alec would always do as he was advised. Much as she liked this impulsive young Scotsman and admired his talents, she deplored his tendency to work himself into terrible states over his experiments and his teaching, and, now, over Mabel. He was so gauche. In New England, gentlemen didn’t behave like that. And there was so much she didn’t know about him. What was his religion, for example? The Hubbards were well-respected members of the local Presbyterian church; only a suitor of sturdy Protestant faith would be acceptable for any of her daughters.

Alec, his hair slicked down with brilliantine and his hands trembling, mounted the steps on that sticky summer day, and once again rang the doorbell. The maid showed him to the sitting room where Mrs. Hubbard, beautifully groomed as always, with her fine white hair neatly pushed under a cap, awaited him. She could not have been friendlier—or firmer. After Alec had perched himself on the velvet-upholstered ottoman, she gently told him that, at seventeen, Mabel was too young to know her own mind, and should be given the opportunity to enter into “Society” and meet other young men. She asked Alec to wait a year before he spoke of his feelings to her. “She promised me,” Alec wrote in his regular letter home to Brantford, “that I should have opportunities of seeing Mabel and said that if my mind was still the same at the end of a year I might speak to Mabel herself.”