Reluctant Genius (13 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Thomas Watson, Alec’s first assistant, was amazed by his new boss’s “buzzing ideas.”

Thomas Watson had enough experience of inventors to know that many of their breakthroughs turned out to be utter failures. Most of the self-taught inventors he had met were wild-eyed eccentrics who shouted orders at everybody and treated metal-shop workers like servants. Thomas Edison, for example, had established a reputation within the Court Street shop as a bad-tempered little bully who bilked his backers and annoyed his fellow workers by chewing and spitting tobacco. Watson wasn’t surprised to find that Alec’s theories were difficult to translate into working prototypes, but he was intrigued by the intense Scotsman. He liked his soft-spoken new boss’s “punctilious courtesy to everyone” and his “clear, crisp articulation.” As the two men got to know each other better, they often spent evenings together, and Thomas began to appreciate that Alec was very different from the other customers he had met. He was deeply impressed by Alec’s table manners (he used his fork, not his knife, to convey food to his mouth) and by the way he could sit down at the piano and immediately begin to play Scottish melodies or Moody and Sankey hymns. “No finer influence than Mr. Bell ever came into my life,” he wrote. “The books he carried in his bag lifted my reading to a higher plane. He introduced me to Tyndall, Helmholtz, Huxley and other scientists.”

In early 1875, Watson began to work almost exclusively on Alec’s harmonic telegraph, usually in a cramped attic above the Court Street machine shop. Alec, for his part, was thrilled to find someone who had the manual dexterity he himself lacked, and who could quietly and accurately translate his scribbled sketches and blotchy instructions into neat constructions. He soon also discovered that Tom Watson was somebody to whom he could confide all his scientific dreams. “His head,” recalled Watson, “seemed to be a teeming beehive out of which he would often let loose one of his favorite bees for my inspection. A dozen young and energetic workmen would have been needed to mechanize all his buzzing ideas.” One day, while walking along the beach at Swampscott with Watson, Alec noticed a dead gull. He “spread it out on the sand,” recalled Watson, “measured its wings, estimated its weight, admired its lines and muscle mechanism, and became so absorbed in his examination that … he did not seem to notice that the specimen had been dead some time.” Then Alec startled the younger man, who was trying to keep downwind of the rotting corpse, with speculation that someone would soon build a flying machine. Three decades later, Alec himself would try to do just that. In 1875, however, the Scotsman’s most stunning revelation to his assistant was his Brantford brainwave: the possibility of an instrument that would allow people to speak directly to each other over the telegraph wires.

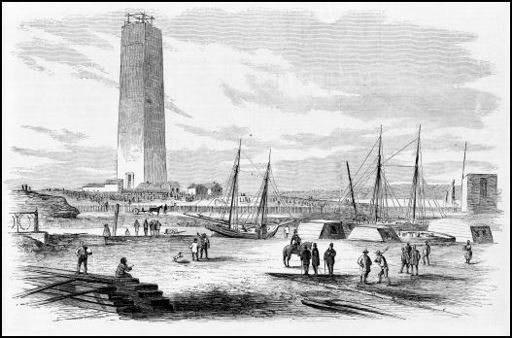

In 1875, the capital of the United States was a shabby, unfinished city, with its half-built Washington Monument.

But the “talking telegraph” was not what Alec’s backers were paying him to produce, and Gardiner Hubbard was impatient with Alec’s tendency to be distracted by his dreams. Gardiner wanted Alec to travel to Washington to apply at the U.S. Government Patent Office for patent protection for his ideas for the harmonic telegraph. This would establish that he was the first inventor to have a workable idea for his invention and would allow him a specified period (usually seventeen years) in which to develop a working prototype. The patent application would be kept secret from other inventors, unless one of them filed a competing application. Alec was reluctant to make the journey: he worried that his ideas were too sketchy and his experimental models too amateurish to submit. The trip would also cost money that he did not have, and would mean missing a week of teaching. But finally, under pressure from Hubbard, he traveled to Washington in late February 1875.

The capital of the United States did not impress its first-time visitor, particularly as compared to Edinburgh or Boston. Ten years after the end of the Civil War, Washington was still just a provincial southern city with pretensions—long unfinished avenues, sparsely settled streets in swampy lowlands. Cows grazed within sight of the Capitol, and cheap stores and hotels lined the muddy expanse of Pennsylvania Avenue. The handful of imposing government buildings made the rest of the city seem even shabbier. The unfinished Washington Monument, on which work had begun in 1848, stood, in Mark Twain’s words, like “a factory chimney broken off at the top.” Alec completed his patent applications as quickly as possible, but then decided to stay an extra day and meet the illustrious Dr. Joseph Henry, who had become first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1846.

Dr. Henry had been playing around with electricity for half a century. In the late 1820s he had helped to demonstrate that if an electric current is passed through a metal coil, it creates a magnetic field around it. His work with electromagnets had led to the construction of an early type of electric motor, which used an electromagnet to convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. Alec was eager to show his telegraph equipment and explain his ideas to this venerable old warrior. An imposing figure with an unnervingly direct gaze and a clipped manner of speech, the seventy-eight-year-old physicist listened silently as the young inventor explained his approach to telegraphy. He nodded thoughtfully, and suggested Alec set up his “harmonic telegraph” equipment on a table in his office. Then he pulled up a chair himself and bent his ear to the coil so he could listen to the different tones that emanated from the receiver. He seemed impressed, so Alec decided not to stop there. “I felt so much encouraged by his interest,” Alec later wrote to his parents, “that I determined to ask his advice about the apparatus I have designed for the transmission of human voice by telegraph.”

The elderly scientist was even more impressed with these ideas. He told the eager young inventor that his idea was “the germ of a great invention,” and he gruffly advised him to keep working at it. A huge grin spread over Alec’s face, but then he remembered his own limitations. Since he lacked the necessary electrical knowledge, he asked Dr. Henry, should he allow others to work out the commercial application of the idea? Memories of his own career must have sprung to the elderly scientist’s mind. Although Henry had been the first person to convert magnetism into electricity, it was British scientist Michael Faraday who had earned the credit for it because he was the first to publish his results, in 1831. Forty-four years later, Dr. Henry didn’t pause for a minute. If this young Scotsman was going to get the commercial payoff from his invention, he simply had to acquire an understanding of electricity. “Get it!” he barked at the twenty-eight-year-old.

“I cannot tell you how much these two words have encouraged me,” Bell wrote to his parents. But his backers balked. They wanted results on the telegraph experiments that would allow two or more messages to be sent simultaneously in Morse code. The wild notion of transmitting the human voice along the wires still seemed impossible to achieve.

Alec also demonstrated his apparatus to the fearsome President Orton of Western Union. Rumors that Elisha Gray was close to perfecting his telegraph equipment had intensified, and Orton made it plain that he preferred dealing with Gray rather than anyone sponsored by Gardiner Hubbard. Under pressure to win the telegraphy race, Alec once again put aside his theories about transmission of the human voice and devoted all his spare time to the experiments he and Watson were conducting. But the stress of increasing debt and growing discouragement soon resulted in headaches and sleepless nights. It was coming up with breakthrough ideas that he enjoyed, not the endless fiddling and fine-tuning they required before they could be taken to market. “I am now beginning to realize the cares and anxieties of being an inventor,” he wrote home gloomily. He felt himself becoming almost unhinged by the pressure. Watson also began to flag as the multiple telegraph refused to perform consistently. He watched Alec lose confidence and work in silence instead of spurring them both on with his accustomed battle cry, “Watson, we are on the verge of a great discovery!”

There was something else unsettling Alec during these months. He was dimly conscious that his feelings toward Gardiner Hubbard’s daughter were undergoing a sea change. He rarely gave her voice lessons these days, but his business relationship with her father meant frequent visits to the Hubbards’ generous home in Cambridge. He began to see Mabel, now seventeen, in a role other than that of an eager pupil. Perhaps he was suddenly vulnerable to gusts of sentiment because the excitement of the multiple-telegraph race had brought him to an emotional boil. Or perhaps it was because Mabel was no longer a child: she was a confident, good-looking young woman with her hair in an elegant chignon and her shapely figure molded by very adult corsets. Often when Alec spent the evenings in Brattle Street he could not take his eyes off Mabel as she sat on the floor, leaning her head back against her mother’s knees so that Gertrude could play with her daughter’s thick hair and stroke her arm.

In late spring, Mabel hosted a small soirée at 146 Brattle Street. “I wish you could have seen her,” Gertrude wrote to Gardiner, “so fresh, so full of enjoyment and so very pretty. She wore her peach silk and looked her loveliest.” She received her twenty guests “with the greatest ease and self-possession,” and when Alec, who had been invited to provide the music, sat at the piano stool, Mabel “led off in a waltz with Harcourt Amory. He is a nice pleasant looking fellow and … one look at her face told how happy she was.” As Alec dutifully stayed at the keyboard, switching from Strauss to Chopin, Mabel twirled through waltzes, gallops, and lancers. When oysters and ices were served at ten, Alec remained quietly in the background, watching men several years younger than he was pay court to Mabel. At the end of the evening, he “finished his kind offices by seeing our friends safely into the cars,” reported Gertrude to her husband. Alec may have assumed the part of a stuffy older brother, but his heart was reaching toward another role.

As Alec’s visits to Brattle Street continued, fourteen-year-old Berta and twelve-year-old Grace Hubbard realized, with the wicked insight of younger sisters, that Mabel’s elocution teacher had fallen for her. They regarded this tall, earnest man, with his hollow cheeks, uncombed hair, and dark eyes, as far too old and serious for their sister (he must be at least

forty).

His manners were too formal, his speech too punctilious, and besides, he wasn’t a Yankee. Various McCurdy cousins joined in the teasing of Mabel’s secret suitor. “We were all anxious to teach the young Scotchman the latest American customs and slang,” recalled Mabel’s cousin Augusta. One day, Alec mentioned that he was going to stay at the Massasat House hotel in Springfield, Massachusetts. When he was advised that he had to try the waffles served at this famous New England establishment, he looked blank: he had never heard of waffles. “Try them with oil and vinegar,” a giggling fifteen-year-old suggested.

Mabel, meanwhile, saw Alec as nothing more than her father’s business associate and her own teacher (although her lessons were usually with Miss Locke). She had been surprised to discover that he was only twenty-eight, and when she sighted the tall figure striding purposefully down Brattle Street, it was hard to imagine that such a serious man nurtured romantic hopes. He was wrapped up in science; he seemed to relax only when Mabel’s mother urged him to sit down at the piano and play some Scottish airs. He was censorious of the way that Mabel’s sisters and cousins spoke—Yankee voices, he insisted, were “harsh and nasal,” and he was sure they could improve their diction if they would only let him help them. And he was obsessed, despite endless setbacks, with getting his complicated sound machines to work.

Alec himself, consciously or unconsciously, was trying to suppress his own emotions. An offhand remark in one of his mother’s letters, about the possibility that he had a mystery girlfriend, prompted a rare burst of self-analysis: “I do not think I am one of the marrying sort. When there is anything of the kind on the tapis [carpet] I shall consult you

first.

I am too much given over to scientific experimenting and to my profession to think of anything of that kind yet and I

doubt very much if I ever shall.

I say this not in joke but in earnest. If I ever marry at all it will not be for years yet.”