Authors: Charlotte Gray

Reluctant Genius (41 page)

But Alec was too wrapped up in his own romantic fantasy of Helen’s future to listen to her doubts. “You are very young,” he told Helen, patting her hand tenderly, “and it is natural that you shouldn’t take what I have said seriously now: but I have long wanted to tell you how I felt about your marrying, should you ever wish to. If a good man should desire to make you his wife, don’t let anyone persuade you to forego that happiness because of your peculiar handicap.”

What prompted Alec to speak like this to Helen? Probably a mix of paternal affection and an undercurrent of sexual attraction that he himself would not have recognized (let alone acknowledged). Yet the conversation reveals so much, particularly Alec’s lack of insight into both his own emotions and Helen. As an inventor he lived in his imagination, yet he was unable to empathize with someone whose life was very different from his own. Helen continued to sit alone on the porch with Alec, and continued to leave her hand in his, but she felt increasingly uncomfortable with the intimacy of the conversation. “I was glad,” she wrote later, “when Mrs. Bell and Miss Sullivan joined us and the talk became less personal.”

Part 3

M

ONSTER

K

ITES AND

F

LYING

M

ACHINES

1889–1923

I never saw anybody who threw his whole body and mind and heart into all that interested him in a hundred different directions, like the waves beating on the shore [that] fling seaweed on the sand and then retreat to fling more seaweed in some other wildly separated place. Papa flings ideas, suggestions, accomplishments upon all recklessly and leaves them lying there to fertilize other minds, instead of gathering them all together to form creations to his own honor and glory.

Mabel Bell to Daisy Fairchild, 1906

Chapter 16

E

SCAPE TO

C

APE

B

RETON

1889-1895

I

n late April 1889, a sharp wind blew off Bras d’Or Lake, and patches of snow lingered on the shady side of the headland. But sap was rising in the dark woods, and the sound of hammers and saws drifted across the water to the village of Baddeck. A large bearded figure, in a baggy tweed suit complete with watch chain, chuckled as he watched a handful of men frame what would be a very special building—the Bells’ first home on their own headland, Beinn Bhreagh.

“I am very much pleased with the site of the new house,” Alec wrote to Mabel in Washington when he returned to the comfort of the Telegraph House that evening. “The more I see of it, the more I like it…. As you row towards Beinn Bhreagh it seems as though the house were built on the very edge of the cliff, and is in danger of sliding down. When you climb up there, you find there is room for a good broad road between the house and the cliff.”

The foundations for the dwelling had been laid the previous autumn, and all winter Alec had chafed to leave Washington and travel north to check on the builders’ progress. Finally, in April, he heard that passageto Cape Breton was possible. He caught the train north to Canada, via Boston—the first stage of the complicated three-day journey to Baddeck. When the train reached Truro, Nova Scotia, he probably took a slow train east across the province toward the Strait of Canso, which lies between the mainland and Cape Breton, and then crossed the strait on a vessel that steamed through St. Peter’s canal, the gateway opened twenty years earlier from the open ocean into Bras d’Or Lake. As the steamer butted its way past shadowy, silent islands, any passengers brave enough to stand on deck in the cutting wind would see seals occasionally surfacing in the chilly waters of the huge inland sea. A few hours later, the steamer arrived at the village of Grand Narrows, where the Barra Strait links the southern half of the lake with the northern half. In the northern half, three deep channels splay out like fingers. Once through the straits, Alec could see north up St. Andrew’s Channel toward Red Head, looming in the distance against the dove gray winter sky.

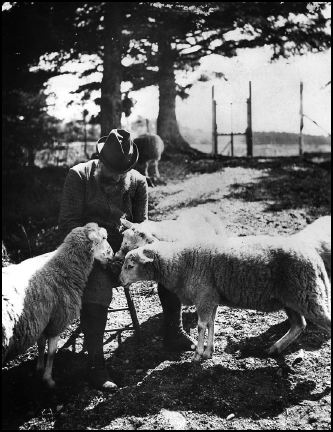

As soon as he set foot in Baddeck, where the Dunlops welcomed him back to the Telegraph House, he felt as though he had come home. He called in at Crescent Grove (the “cottage on stilts” where the Bells had spent the previous three summers) and was greeted by a procession of sheep. (“First there was Minnie, followed by her daughter Nellie, followed by her son, what’s his name, and a little baby lamb born only a few days ago. Minnie also has a lamb born today so there will be five in the procession when the children arrive.”) And when he had found a row-boat and rowed himself across Baddeck Bay to his beloved headland, he found his team of local workmen hard at work: “The tree trunks that are to form the verandah poles are cut and ready to be placed in position… . There is a great deal more stonework about the house than I had any idea of… . The different parts of the house are being riveted together with iron. … It looks therefore as if it will require a two-fold Samoan hurricane to move the building from its place.”

This new house, which had been sketched out by Arthur McCurdy and Alec and named “the Lodge” by Mabel, was intended only as a temporary residence. Still flush with more capital and income than they had ever imagined, the Bells were already thinking much bigger. Once Alec had managed to buy all the land on the headland, they planned to build a grand mansion, designed by a Boston architect, on the tip of the headland. The Lodge was therefore modest—too modest, it quickly emerged, given the Bells’ love of guests. It originally included only four bedrooms, with two-level rustic verandas on all four sides. Within months, as friends and family members began arriving, the verandas were enclosed to provide extra sleeping accommodation. One of those visitors was acerbic cousin Mary Blatchford from Boston, who sniffed that the extra rooms “hurt the architecture.”

Alec and Mabel rowing in Beinn Bhreagh bay, below the Lodge.

That first April, Alec was thrilled to be back in Baddeck, despite the icy winds and unexpected snow squalls. He would stand on Beinn Bhreagh, taking great gulps of Cape Breton air and letting his gaze skim down the ten-mile length of St. Andrew’s Channel to Grand Narrows. The frustrations and worries that haunted his Washington life—his inability to get launched on a new invention, Mabel’s yearning for another child, his conflict with Edward Gallaudet—fell away. “For the first time in months, I have been able to take exercise without perspiration. I have certainly walked not less than six miles a day since I came to the island,” he bragged to Mabel that month. “I never felt better in my life.” Alec’s enthusiasm for cold, damp weather knew no bounds. While Cousin Mary was staying, a violent storm broke one night: “[T]he rain it rained,” she wrote to a friend, “and the wind it blew, the trees slapped and shivered and bowed like mad things ... and all Nature was in a frenzy.” She was horrified when Alec announced he was going to walk up the mountain during this downpour, and even more appalled when he donned his slippers and swimsuit (“a closefitting dark blue jersey,

very

becoming”) for the outing. By three o’clock in the morning, everybody was downstairs. Mabel watched lightning zigzag across the lake; her guests jumped each time they heard thunder roar or branches splinter; the driving rain leaked through the window frames.

Where

was Alec? Suddenly, there was a tap on the window. “There stood Mr. Bell,” Mary Blatchford recorded, “dripping like a merman, and looking as handsome as an Apollo, with his gray curls wet and shining, and his white arms and legs.”

There was a new energy in Alec’s step as he strode around the headland, planning roads and buildings and convincing Cousin Mary that “all men are boys.” In Cape Breton, he could be himself in a way he could never be in Washington, with its snobbery, racism, and unbearably humid summers. He was invigorated not only by the bracing Atlantic air but also by the locals’ amused tolerance of the Great Man who had turned up in their midst.

Baddeck s taciturn Scots residents, most of whose families had lived in Cape Breton for at least three generations, found Alec an exotic creature, with his British accent, American wife, international reputation, and untold wealth. But by 1889, after four summers, the Bells had proved they were not just another set of American tourists, come to stare at the natives. They had endeared themselves to their neighbors and had begun to create their own world. Alec shed the Washington uniform of morning coat and stiff collar and wore comfortable tweed knickerbockers and a flat cap. As a child in Edinburgh, he had been ignorant of the Highland customs and mythology that Scots emigrants had brought to Cape Breton half a century earlier; he had never worn a kilt or played the fiddle or the bagpipes. But Cape Bretoners’ dry humor and love of music made him feel at home. The men of Baddeck often gathered on Sunday evenings to sing Scottish ballads, and he regularly added his rich baritone to the chorus. Alec’s imagination, no longer smothered by the hauteur of Washington, was fired up. He started thinking about the kind of scientific experiments he could pursue on Beinn Bhreagh’s gently sloping acres. His next great passion was unfolding.

This passion grew out of his research on the family histories of deaf people. Genetics was still a little-understood science, although the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel had published evidence of inherited traits, based on his experiments growing peas, as early as 1865. The word “genetics” would not even be coined until 1905. So Alexander Graham Bell was groping in the dark as he tried to understand the role played by genetic heritage. His study of the transmission of deafness through several generations of Marthas Vineyard families in the village of Squibnocket had alerted him to patterns of inherited characteristics. He had stumbled on the existence of dominant and recessive genes, even though he never knew those labels. And he had the perfect open-air laboratory in Cape Breton: his first scientific adventure involved selective sheep breeding.

A flock of sheep had come with a parcel of land he purchased in 1888, and while the Lodge was being completed, he ordered the flock to be turned loose on Beinn Bhreagh’s hilltop. “We have about fifteen lambs so far,” he reported with excitement to Mabel in April, “and expect many more about May 1st.” When one ewe lost her lamb, he designed a pen that would force the ewe to adopt one of the twins born to another ewe. “The experiment has been a grand success,” he wrote home. “Today they seem to be fast friends.” He was particularly interested in exploring why some sheep had a rudimentary set of extra nipples, besides the functioning pair, and whether these extra sets were related to a ewes propensity to multiple births. His goal was to breed ewes that would regularly produce twins or triplets and then provide milk through several nipples simultaneously, as a sow does for the several young piglets that are the norm in every pig litter. In other words, Alec wanted to breed a superflock of sheep.

Alec studied genetics through sheep-breeding experiments, which provided another excuse to remain in Nova Scotia.

Alec loved the idea that, in pursuit of his own scientific interest, he might benefit the people among whom he was now making his summer home. His specially bred sheep, he reasoned, would double a farmers income without materially increasing his labor. He started to dream about fecund ewes filling the pastures of Cape Breton with crowds of gamboling lambs and swelling the emaciated wallets of the island’s weather-beaten farmers. By the time Mabel arrived in June, a series of sheep pens, named “Sheepville,” had been constructed at the end of the headland, to house all the lambs that were twins or had extra nipples.

Though Mabel had remained in Washington, Beinn Bhreagh was never far from her thoughts. “Do order trees planted immediately,” she asked Alec. “Please order a lot of white pine (pinus strobes), white ash, sugar maple, locust (robinia pseudacacia).” Cape Breton assumed almost as much psychic importance for her as for Alec. Like Alec, Mabel was in love not just with its scenic grandeur but also with the sense of release it gave her. Her deafness constrained her less there than anywhere else in the world, because it seemed less of a stigma in Baddeck. She was already regarded as a bit of a hothouse flower by Cape Bretoners, with her fashionable gowns and sweet manner, so that her odd speech and her habit of watching their lips closely were just more aspects of her strangeness. The rural community was more tolerant of idiosyncrasy than the American elite. Mabel felt very comfortable in Baddeck. Like Alec, she was stirred to take initiatives that would benefit those who were helping them make their summer home in Cape Breton.