Reluctant Genius (19 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Alec’s mother, Eliza, was the person most concerned about Mabel’s deafness. She had no way to communicate with her future daughter-in-law. Neither of them knew the Abbé de L’Epée’s sign language, and Eliza could not read lips. She depended increasingly on the double-handed finger language with which Alec had communicated with her since his Edinburgh childhood, and which her husband now used regularly with her. Mabel depended entirely on lip-reading, so she would be able to “hear” what Eliza said to her but Eliza would not hear her replies. Still, Eliza longed to meet this young American woman with whom her son was so besotted: she could see that Mabel was a wonderful influence on her only son. She sent Alec some moonstones for Mabel’s engagement ring. How, though, would she be able to understand Mabel, particularly if her speech was indistinct? “Ask her to learn the double-handed finger alphabet for me,” Eliza pleaded with Alec. “She need not fear yielding to the temptation of using it too frequently, for few besides ourselves understand it.” But Mabel never learned the double-handed alphabet, relying instead on Alec to be the intermediary between her and her future mother-in-law.

Alec was now far more cheerful than he had been the previous year.

Still, when he reflected on his future, he felt shackled by poverty. The Hubbards would not entertain any discussion of a date for their daughter’s wedding until Alec was in a position to support Mabel. Mabel urged him to focus on the commercial potential of the telephone because she knew it could secure their future together. But Alec’s business partners, Hubbard and Sanders, were not eager to sink funds into developing and manufacturing the telephone until they were confident that a market existed for it. Too many people regarded it as a toy that could never replace the telegraph because it didn’t leave a printed record. At Western Union, William Orton was pumping money into Thomas Edison’s version of the quadruple telegraph, by which two messages could be sent in one direction and two in the other. A Western Union electrician had sent the company president a memo suggesting that “[t]his ’telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us."

In May 1876, Alec began giving a few public demonstrations of his prototype telephone with the help of Mabel’s twenty-six-year-old cousin William Hubbard, a Harvard student. This very first telephone certainly had shortcomings. It could carry sounds only one way, over a short distance, and the quality of transmission was unreliable, so demonstrations always included some well-known musical passages as well as the spoken word. The first was to “a dignified assemblage of greyheads” at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in the Boston Athenaeum, and the second, a few days later, to the Society of Arts at MIT. Alec and Willie would rig up their primitive transmitter in a nearby room, then connect it by wire to the receiver in the lecture hall. At the end of Alec’s lecture, Willie would transmit some music (the hymn “Oh God Our Help in Ages Past” was a popular choice) and then a familiar passage of poetry. Few of the words in Willie s rendition of a soliloquy from

Hamlet

were clear, but according to the

Boston Transcript,

the audience was impressed. “I feel myself borne up on a rising tide,” Alec wrote to his parents.

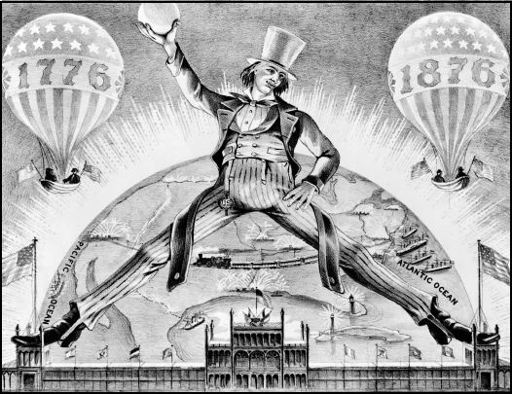

A poster entitled "Stride of a Century" caught the atmosphere of the philadelphia

Ever the entrepreneur, Gardiner Hubbard knew that a few lame demonstrations in front of a bunch of university professors were not going to raise any capital. He was looking for major investors. He was eager for Alec to use a much more ambitious launch pad for a scientific breakthrough: that summers much ballyhooed World Exhibition. Held in Philadelphia, the city in which the Declaration of Independence had been signed a century earlier, the exhibition was going to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the American Revolution. It had already involved ten years of planning; it would cost more than $11 million, and Gardiner himself was one of three prominent Bostonians charged with organizing the Massachusetts contribution to the education and science section.

The Philadelphia Exhibition put America on exuberant display to itself, as the nation emerged from the economic depression and wrenching dislocation that had followed the Civil War. The 285 acres of fairground in Fairmount Park teemed with invention, appetite, avarice, and optimism as Americans showed off their industry and creativity. There were seven major exhibition buildings plus nine foreign pavilions and seventeen state buildings (only two, however, from southern states, which had been devastated by the Civil War). The buildings were linked by a narrow-gauge railroad. The exhibits reflected the tastes of the times. The Horticultural Hall represented the Victorian love of exotic gardens under glass, while anti-liquor reformers made their point with their monumental Total Abstinence Fountain. Among the 22,742 exhibits, familiar artifacts (machine-made shoes, bone corsets, sewing machines) jostled with exciting innovations (canned foods, dry yeast, mass-produced furniture, linoleum, ready-made clothing). In the Women’s Pavilion, Mary Potts s patented flat-iron and Margaret Calvin’s Triumph Rotary Washer illustrated the application of new technology to traditional women’s work.

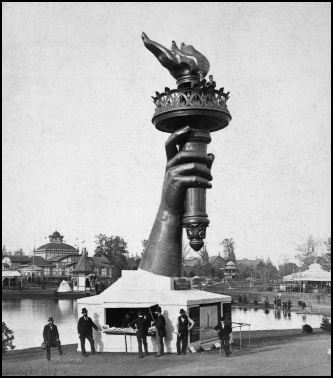

Bartholdi's Electric Light gave Americans a glimpse of the future.

There was a heady, forward-looking momentum, as large numbers of visitors sampled for the first time such novelties as bananas (separately packaged in tinfoil and costing ten cents), popcorn, Hires Root Beer, and ice cream sodas. The most thrilling outdoor feature was Bartholdi’s Electric Light, or the Colossal Arm of Independence. This monumental arm, holding aloft a brilliantly lit torch and created by French sculptor Frederic Bartholdi, was a stunning spectacle. Ten years later, Americans would be even more dazzled by it when the complete Statue of Liberty of which the colossal arm was a component was erected in New York harbor.

The exhibition opened on May 10, with a march composed by Richard Wagner and an address by President Ulysses S. Grant. President Grant’s most distinguished guest for the ceremony was an engaging, progressive-minded eccentric: Pedro II, emperor of Brazil. Dom Pedro, as he insisted on being called in the American Republic, had inherited the throne of Brazil in 1831, when he was only five years old. At home, the forty-one-year-old emperor was usually decked out in a splendid Gilbert-and-Sullivan-style uniform festooned with ribbons, medals, outsized epaulettes, and gold braid, but on this occasion he sported a frock coat with a heavy gold watch chain strung across his well-filled waistcoat. An energetic autodidact, as a youth he had mastered French, Hebrew, Arabic, and Sanskrit, as well as many of the Tupi-Guarani languages indigenous to South America. He was now a passionate opponent of slavery within his realm.

The 70-foot-tall Corliss steam engine, weighing 56 tons and producing 1,400 horsepower, drove all the exhibits in the Centennial Exhibitions Machinery Hall.

Dom Pedro could barely take his eyes off the exhibition’s central attraction: the Corliss steam engine—the largest steam engine in the world. He puffed up the ladder onto the engine s platform after President Grant, and stared with amazement at the mighty cylinders. He watched the president hit the levers that allowed steam into the cylinders, heard the engine hiss, and felt the floor of the thirteen-acre Machinery Hall tremble. He stared in wonder as the huge walking beams slowly started to move up and down, feeding the giant flywheels that spun around, gaining momentum and storing energy. Seventy-five miles of belts jerked into action, causing the shafts and pulleys of the steam engine to drive lathes and saws, drills and looms, presses and pumps. Thanks to the Corliss, the

New York Tribune,

the

Boston Herald,

and the

Philadelphia Times

printed their daily editions at the fair.

Dom Pedro was not the only observer left slack-jawed by the Corliss steam engine. Over the next four months, almost ten million people came to watch the mechanical behemoth that symbolized the raw power now driving Americas industrial revolution. But it was another aspect of the Philadelphia Exhibition that captivated Gardiner Hubbard, who made repeated visits to this huge national birthday celebration. He had secured space for Alec’s prototypes of both the multiple telegraph and the speaking telegraph, along with a display of Visible Speech charts and books. Now he watched scientists and wealthy investors pacing down the Machinery Halls aisles, comparing different innovations. He saw Elisha Grays and Thomas Edisons diagrams and proposed inventions displayed prominently, and Alec’s rivals often present in person, drumming up interest in their work. Gardiner sent an urgent telegraph home. Alec, he insisted, must drop everything and appear in Philadelphia for Sunday, June 25, when the Committee on Electrical Awards was scheduled to decide which piece of electrical apparatus should receive a medal. Sir William Thomson, the famous British physicist from Glasgow University who had helped design the first transatlantic cable, was chairman of the committee. Alec

had

to be there to demonstrate that his prototype of the telephone, with the makeshift mouthpiece and tin cup of acid at the transmitter end, was the communication device of the future.

But Alec had other ideas. He was preoccupied with preparing his students and his teachers of the deaf for their final examinations. He had already suffered the interruption of a visit to Boston’s School for the Deaf by Dom Pedro, during which he had explained Visible Speech to the genial ruler, and arranged for two of his father’s books to be sent to Brazil. Why should he now desert his professorial duties for the hoopla and frenzy of Philadelphia, which he knew would be hot, sticky, and crowded? He ignored his future father-in-laws telegrams.

So Hubbard tried a different tack. He sent a telegram to Mabel and her mother, explaining the vital importance of Alec s presence in Philadelphia. In Cambridge, Mabel recognized the validity of her fathers arguments. She also knew that Alec was a born tinkerer. Unlike Thomas Edison, the ruthless self-promoter who saw science as Darwinian competition and who always announced his inventions before he had even got them working, Alec hated revealing anything until he was confident of its success. Edison was an ambitious self-made American; Alec was a cautious Scot more interested in scientific progress than commercial success. And now he was putting loyalty to his students and his father (who had recently reproached him with “poking over experiments" instead of promoting Visible Speech) ahead of capitalizing on his breakthrough and his future father-in-laws investment.

Mabel took matters into her own hands. She tucked her hair into a bonnet and asked for the Hubbard carriage to be brought to the door of 146 Brattle Street. Then she told the coachman to drive her to Alec’s rooms, and insisted to Alec that he stop drafting exam papers and accompany her on a drive. Before Alec realized what was happening, he found himself at the railroad station, where his fiancée handed him both a ticket to Philadelphia, via New York, and his valise, which she had secretly packed. A bewildered Alec stared helplessly at Mabel, then refused to get on the special Saturday excursion train, which was already getting up steam for the journey.