Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (18 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Rhau-Grunenberg had done a reasonable job as a printer of simple Latin texts for the university, but when he continued in the same style with Luther’s writings, the relative crudity of his work was all too apparent.

THE FORTUNES OF TRADE

In 1515, we will remember, Luther did not rate a mention in a list of the top one hundred professors of three rather obscure German

universities. In the two years 1518 and 1519 he became Europe’s most published author. His fame, and for the first time his image, was spread around Europe in numerous published works, in Latin for the international scholarly community, in German for the new audience Luther was building for his unique mixture of theological controversy and pastoral instruction. In these two years Luther had written 45 original compositions: 25 in Latin and 20 in German. No wonder by the time he appeared at Leipzig he seemed to have been reduced to skin and bone; the work, and the nervous tension of constant danger, had worn him away. But he had done what was necessary to grasp his moment of opportunity; the printing industry, and the popularity of his writings among an expanding reading public, had done the rest. The 45 works published by Luther translated into a total of 291 editions by the time German printers had met the huge public interest with instant reprints and the first anthology volumes; and then, of course, there were the works of friends and adversaries.

27

It is worth pausing to consider the impact of this great rush of print on the German printing industry: how indeed it could cope with such a sudden new demand for works of urgent topical interest.

In 1515 and 1516 German print shops turned out something over eleven hundred titles. This was already impressive, and far in excess of the output of both France and Italy, the other two major European centers of print activity. The print trade in these other markets was structured rather differently. Although in France and Italy, Paris and Venice played a dominant role, in Germany production was far more widely dispersed. Only Leipzig, and less reliably Strasbourg, would be responsible for more than one hundred titles in any one year.

This, as it turned out, created the ideal conditions for the rapid dissemination of Luther’s writings. Generally the first edition would be put to the press in Wittenberg, in the single then-operating print shop of Johann Rhau-Grunenberg. It would then be rapidly reprinted in Leipzig, fortuitously close, and home to several well established publishing ventures. From there the text could be relayed on to Nuremberg, Augsburg, and thence onto the great cultural capital of the Rhineland, Basel.

In some respects it served the movement well that Wittenberg, at this point, was simply too small to cope with the extraordinarily rapid increase in demand for Luther’s works. Rather than centralizing production in one place, and facing the complex tasks of distributing stock over large distances, it made far more sense to dispatch a single copy to new markets, where a new edition could be printed off. This was particularly the case with small books, as the capital investment required to publish a small pamphlet was relatively modest. With large books, the risk of two presses embarking on competing editions and having large amounts of unsold stock tipped the balance in favor of centralized production. And many of Luther’s works, as we have seen, were very short, allowing them to be reprinted very quickly. A well-organized print shop could print five hundred copies of an eight-page pamphlet in a day.

What was so remarkable was how quickly, instinctively, Luther adapted his writing to optimize benefit for the printing trade. Of his forty-five writings of these years, twenty-one were eight pages long or less. The demand and public interest meant that they often sold out very quickly. Printers got an immediate return for minimum investment. Luther, it very quickly became clear, was a safe bet for the printing industry.

The impact of the Reformation on a local printing industry can be very well illustrated with the example of Augsburg.

28

Augsburg was one of Germany’s proudest and most sophisticated cities, a major center of commerce and international finance. It was also a major information crossroads, the only one of the free cities that lay on the route of the imperial postal service. But in 1517 its printing industry experienced something of a hiatus, publishing only 37 titles in the whole year. Augsburg had no university, so lacked that important local market. In the years that followed, the Luther affair sparked a major regeneration. Overall production rose to 89 titles in 1518 and 117 in 1519; Luther accounted for 41 of these extra editions. In 1520 Augsburg’s printers would publish a staggering 90 editions of Luther’s works.

29

The case of Basel was rather different; this rich, cultured city embraced Luther in a much more measured way. Whereas the largest

portion of the Augsburg Luther editions were in German, Basel’s main contribution was a series of reprints of Luther’s Latin books, including, as we recall, the first edition of the ninety-five theses in pamphlet form.

30

This was the work of Adam Petri, who would go on to publish over a hundred Luther editions in the next ten years. In the first years, however, the crucial contribution was made by Johann Froben, Erasmus’s long-term collaborator. In October 1518 the enterprising Froben published an anthology of six of Luther’s Latin works on the indulgence controversy. This was enormously successful: Froben sent copies all around Europe and claimed to have disposed of the best part of six hundred in Paris alone.

31

His initiative was rapidly plagiarized by Matthias Schürer, in Strasbourg, another western city extremely well-placed for international sales. Schürer’s editions offered much the same selection, with the addition of the

Acta Augustana

.

32

Froben might have been sore at this raid on his market, but the absence of copyright protection in the patchwork of political jurisdictions that made up the German Empire actually helped greatly in assisting the rapid spread of Luther’s work. There was nothing to prevent a printer in one city or state from republishing the work of a printer in another, and, of course, Luther as author received nothing from the sale of his works. Froben would later recall rather ruefully that his Luther anthology was his most successful title, somewhat to the chagrin of Erasmus, who insisted that Froben abandon publishing Luther if he wanted their own relationship to continue.

33

The impact of the Luther controversies on the print industries of Augsburg and Basel was indicative of a more general revival of printing in the German lands. The interest in Luther allowed printers to make quick profits, which they could then reinvest in other projects. Overall the number of titles published doubled between 1517 and 1520, reaching a new peak in 1523: at this point German presses published three times the number of books printed in France and Italy combined.

34

This raises the question of how it was possible for the industry to expand production so very rapidly. Undoubtedly, in 1515 there was spare capacity, with many presses rather underemployed. Where new print shops

were established, or existing businesses expanded, the capital costs involved were relatively modest: a wooden press could be constructed very quickly and was a relatively simple piece of machinery. The principal bottlenecks would have been the casting of new type and the supply of paper. With respect to type, Germany was lucky in possessing Europe’s most advanced metalwork industries (in which Luther’s father, we will remember, had made his living).

With respect to the supply of paper it helped that the industry was so dispersed, and so could rely on several major areas of paper manufacture. But this was certainly a major concern: it is revealing that when Lucas Cranach, Wittenberg’s canniest businessman, decided to invest in the printing industry, he bought his own paper mill so that he could be assured of adequate stock.

35

Other major publishers made similar investments; for those with more modest resources paper could often be obtained by exchange—taking so many reams of paper in return for half as many printed sheets, which the paper barons could then sell. This reflected the customary calculation that paper represented about 50 percent of the cost of the finished book. It is also the case that the increased demand for paper would have been rather lower than the raw figures for number of editions published would suggest. Many of Luther’s works, and those published by his colleagues and adversaries, were very short. A sixteen-page pamphlet in quarto would require only two sheets of paper per copy, a thousand sheets for an edition of five hundred. So a great deal of the apparent increase in output could be accounted for by displacing work on larger books to publish Luther.

This was an extremely attractive proposition for book-trade professionals. Publishing large books could be extremely risky. A Latin tome of five hundred pages required an enormous stock of paper, and might take up to a year before the printing was complete and the first copies could be sold. A printer had to have good credit to meet these costs (and those of wages and maintaining the print shop) before sales could recoup any of the investment. Worse, it was by no means certain that the copies would sell; the publisher had to allow for heavy discounts to move the

stock, and heavy costs in transporting the texts to a widely dispersed readership. Each new book was a risky business: underestimate demand and the work of resetting the text for a new edition would take another year; overestimate demand and one might never make back the costs, with a large portion of the expensively printed sheets rotting in storage for years.

36

With a Luther pamphlet, the job was ready for sale in a couple of days, sale was virtually assured, and with German titles the market was largely local. All the complexities of the trade, which brought financial embarrassment to so many publishers, seemed to have been resolved. It was no wonder that printers came to love Luther, and Luther came to transform the German printing industry.

OLD MAN RHAU

The question remained how much of this buoyant market could be reserved for Wittenberg. By 1518 the inadequacies of the local industry were all too obvious. In any circumstances one press would have been insufficient to meet the enormous demand for Luther’s work. That this press was in the hands of Johann Rhau-Grunenberg was a recipe for embarrassment and frustration.

As we know, Luther had always had problems with the quality of Rhau-Grunenberg’s work. In these years of controversy and rapid pamphlet exchanges this was further compounded by Rhau-Grunenberg’s inability to work at anything other than his own stately pace. In 1518 matters began to come to a head. The time Rhau-Grunenberg took to publish Luther’s full statement of his views on indulgences, the

Resolutiones,

had had calamitous consequences, as the maliciously constructed version of his sermon on excommunication was allowed to circulate without reply. Rhau-Grunenberg could not make space to publish the true text until several months later, at which point the damage was done. Rhau-Grunenberg might protest that the

Resolutiones

needed to be published with care, since it was destined to pass into the hands of senior

churchmen, but in this case slow did not mean better. Luther thought the quality of the final product embarrassingly deficient.

37

Significantly, Luther attributed this to his long absence at the meeting with Cajetan in Augsburg, the implication being that in normal circumstances Luther took care to exercise close supervision over the printing process. This was not unusual for authors in this period: by far the best way to avoid irritating errors in the texts was to check the proof sheets oneself, but since the sheets were set up one at a time this demanded almost daily attendance at the printer’s shop.

With Rhau-Grunenberg overtaxed, Luther was forced to send a number of original texts to Leipzig for publication.

38

This, though, had its own drawbacks. It was dangerous, since a manuscript could be lost on the road or fall into the wrong hands. In this case, too, Luther could not be on hand to check the accuracy of the printer’s work. The logical solution was to persuade a further printer—or printers—to open a business in Wittenberg. And this, in addition to all his other responsibilities, Luther now decided to pursue.

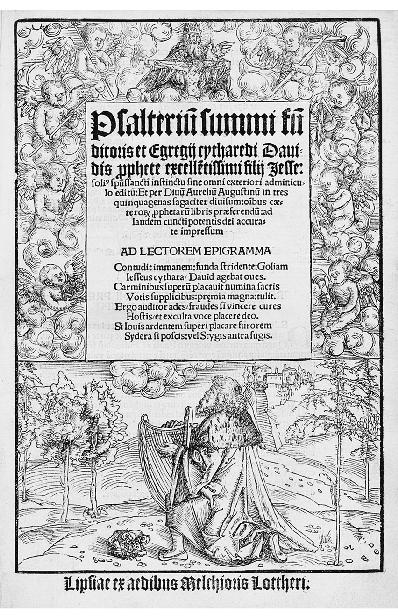

His choice fell on Melchior Lotter, one of the best established of the Leipzig printers.

39

Lotter was by now a veteran of the German print world, having first published books in Leipzig as long ago as 1495. He had built his business steadily, and by 1517 he had almost five hundred titles to his name. This in itself would not have been enough to account for Luther’s preference. The even more prolific Martin Landsberg also plied his trade in Leipzig, and had an established relationship with Wittenberg University: between 1507 and 1511 he had published a number of works for Christoph Scheurl and other of the Wittenberg literati.

40

It was a third Leipzig printer, Jakob Thanner, not Lotter, who had published the Leipzig edition of the ninety-five theses, though he had made such a poor job of it this may have ruled him out of contention.