Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (43 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Luther’s influence was also increasingly felt beyond the borders of Electoral Saxony. His friendly relationship with neighboring princes could be called upon to prevent the publication of editions that breached a Wittenberg monopoly. In 1539 the death of his old antagonist, Duke George, and the accession of his brother Henry brought about a rapid conversion of Ducal Saxony to the evangelical cause. This was undoubtedly welcome, but not without danger to Wittenberg’s printers, particularly if it sparked a revival of Leipzig’s moribund printing industry. Leipzig’s printers, who had lived off the thin gruel of Catholic polemic for twenty years, were naturally eager to share in the much more robust Protestant market. This applied even to Nikolaus Wolrab, whose press had been established specifically to publish the works of his uncle Johannes Cochlaeus. Now to his patron’s horror he proposed to revive his fortunes by publishing an Edition of the Wittenberg Bible. Luther was equally scandalized, and he appealed to Elector John Frederick (who had succeeded his father in 1532) to make representations to his cousin. “How unfair it is that this scoundrel should be able to use the labor and expense of our printers for his own profit and their damage.”

46

Here Luther articulated the classic printing industry argument for market regulation, that the prior investment of the first printer, on editorial work, translation costs, new types, or woodcuts, should be protected against competition. He then added a further very interesting remark. “It can easily be figured out that the printers at Leipzig can more easily sell a thousand copies, because all the markets [fairs] are in Leipzig, than our printers can sell a hundred copies.”

T

HE

L

AW AND THE

G

OSPEL

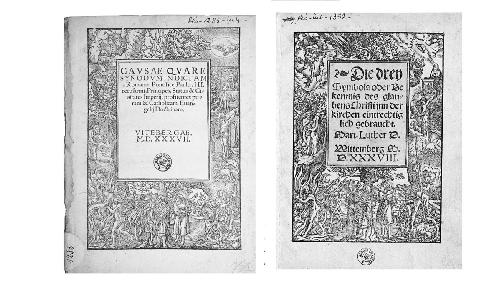

Cranach’s most original iconographical creation, here adapted for book-title pages in two subtly different versions.

This certainly expressed the historic relationship between Leipzig and Wittenberg, but it is very doubtful that this was any longer the case. Wittenberg’s powerful publishing consortia, who now undertook much of the work of wholesaling and distribution on the printers’ behalf, had

developed highly efficient means of bringing their books to the marketplace. In the event, Leipzig never did recover fully the ground given up in the two lost decades. Rather, the opening up of its fairs to Protestant literature only further strengthened Wittenberg’s access to its markets. Wittenberg would remain the regional capital of print to the end of the century.

47

This, of course, could not all have been foreseen in 1539, when the new competition from Leipzig seemed all too daunting. This awareness of the fragility of the market, and its utter dependence on Luther, helps explain one remarkable conversation that took place in this same summer. Around the end of June, quite probably when news of the proposed Leipzig edition of the Bible had reached Luther, the printers of Wittenberg approached him with an extraordinary proposition: that in return for a guarantee of first access to any future works they would provide him with a supplementary annual income of four hundred gulden. This was serious money: Luther’s salary was never above two hundred gulden; this would have tripled it.

Luther refused: he preferred to make no money from his books, written always in God’s cause, and to give no further ammunition to his enemies by profiteering from God’s work.

48

Actually he could now well afford this high-mindedness, thanks partly to his businesswoman wife, who kept the household well provided for and brought in considerable extra income from her various business ventures. Although he complained intermittently of money worries, Luther was actually comfortably well-off. That is not the real point. What is remarkable about this story is that the printers were prepared to pay so much, at a time when Luther’s productivity was declining steeply, for what in any case he provided them for free. There could be no more graphic demonstration of Luther’s personal importance to the industry that made Wittenberg—and indeed made the fortunes of the friends in the industry whose generosity Luther now politely refused.

One can well understand the ties of affection and obligation that bound Wittenberg printers to “Father Martin.” Luther’s oversight of the

industry was all-embracing. Printers relied on access to the valuable first editions of Luther’s copious writings, as well as those he sponsored for others. In addition he exercised an effective veto over anything he or his university colleagues deemed to be unsuitable. No printer who wanted to work again would think to challenge this authority. In this way Luther exercised near total control over the flow of texts that publishers needed to obtain to sustain their business. Yet printers were happy to work within these constraints, since the profits to be made were great and the work so reliable. They knew, as did Luther, how much his works were worth in the German marketplace. A preface by Luther could justify a new edition of a work already published elsewhere in Germany;

49

the presence of Luther’s name could add value to the first edition of a sermon or catechism by an otherwise obscure author. As Luther rather guilelessly acknowledged in the preface to one of the works contributed to the campaign against Erasmus, “The printer has pried from me this preface that is supposed to be published under my name, so that this little book, marketable enough by itself, might be regarded with all the more favor on account of my endorsement.”

50

From the first days when his writings revolutionized production in Wittenberg, to the end of his life and beyond, Luther was the true patron saint of the Wittenberg printing industry. By the last decade of his life the industry was sustaining several hundred employed directly in the business of books and others in ancillary trades.

51

If one factors in the hundreds of students drawn to Wittenberg to study, and those who lived on servicing their needs, it is clear that Luther was the major motor of the town’s revived economy. No wonder he could rely on a cheerful greeting as he plodded through its streets.

11.

E

NDINGS

N 1537, WHEN

N 1537, WHEN

L

UTHER

entered the last decade of his life, he had lived in Wittenberg for twenty-six years: six in relative tranquillity as a young and comparatively unknown professor, followed by two decades in the maelstrom unleashed by his challenge to the church hierarchy. This had been a turbulent, often frantic time, and Luther’s last years would bring no real relief. The calls on his time and expertise were incessant, an endless round of appeals for his judgment, letters to write, advice to princes, all, of course, alongside the day-to-day duties in Wittenberg. There was no letup either in the demands for new works from his pen. The next ten years would see Luther make frequent and influential contributions to several new and ongoing controversies. Readers seeking the familiar truculence and passion would not be disappointed, though the vivid writing of these last battles could also take on a darker, more menacing tone.

All of this made enormous demands on a man who could no longer call upon the boundless reserves of energy that had sustained him through the first Reformation controversies. The self-confidence and charisma were undiminished, but the body was failing. In 1537 Luther was fifty-four years old; not old by today’s standards, but in an era when medical treatment could do little to alleviate the pains of illness or

chronic conditions—or even provide accurate diagnosis—the wear and tear led to increasingly severe health problems.

Luther had always suffered problems with his digestion. The letters from the Wartburg in 1521 offer an obsessive and at times all too detailed narrative of his battles with constipation. The pleasures of a settled home and Katharina’s market garden helped to some extent in this respect, but as Luther lost some of his physical vitality other problems intervened. In 1527 he collapsed in the pulpit while preaching, the first of many dizzy spells that troubled and disorientated him thereafter; these attacks could also leave a residue of ringing in the ears that persisted for months. Luther also began about this time to experience the first symptoms of angina; in December 1536 he would suffer a severe heart attack. From 1533 Luther also had to deal with the dreadful and debilitating pain of kidney stones. This was a common condition in the sixteenth century, particularly among those who ate a richer diet; Luther, who loved the pleasures of the table, was always a likely victim. The result was frequent, incapacitating pain, which only exacerbated Luther’s problems with his digestion. In 1537, while at an assembly of the Protestant League in Schmalkalden, Luther suffered a urinary blockage so severe that his friends feared for his life. An operation was considered, but without anesthetic the chances of survival were grim, and Luther was in any case too weak for this to be contemplated. The crisis passed, but recovery was slow. In 1538 his entire family was struck with dysentery; in 1541 he developed a painful abscess in the neck and suffered a perforated eardrum.

Luther was by this point an old man, in almost constant pain, dosed by doctors, tended by an anxious wife, but beset always by constant work, the press of problems humdrum or acute that would inevitably be referred to him so long as he drew breath. So if during these last years his judgment or his temper failed, we must bear in mind that like many in this era he lived his life in a constant state of low-level illness or debility, flaring up into acute episodes in which the agony was unbearable. At such times Luther longed for the death that would free him from these burdens. But it would, in fact, be another decade since his life was first

despaired of in 1536 before his release would come. In this extra ten years much would be done to secure his movement, whatever the cost to its indispensable leader.

THE PRINCES’ FRIEND

Luther’s attitude to authority—not least his own—was complicated and shot through by contradictions. In the first years of the Reformation more pacific spirits had recoiled from the radical implications of his assault on the church hierarchy. But while Luther made no apology for his treatment of the pope and his minions, in other respects he was profoundly conservative. Attempts to introduce precipitate change into the worship service at Wittenberg left him deeply uncomfortable, and he never wavered in his support for the established civil order. How Christian freedom and the restraint of licentiousness should be reconciled was a question to which he first systematically addressed himself in a series of sermons in 1522. These became the important tract

Secular Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed,

published in the following year.

1

Here Luther laid out for the first time his doctrine of the two kingdoms: the spiritual kingdom, in which man exists purely in relationship with God, and the temporal kingdom, in which man’s fleshly needs and sinful nature have necessarily to be restrained by the exercise of civil authority. The events of the Peasants’ War in 1525 only confirmed Luther in this sense that society required firm and sometimes cruel regulation, and that the current order of government in Germany was ordained by God for this purpose. To those who charged him with responsibility for the peasant uprisings he would reply with justice, if somewhat defensively, that “the temporal sword and government have never been so clearly described or so highly valued as by me.”

2

Any sort of resistance to properly ordained government was something to which he was viscerally opposed.

For all that, the distinction between spiritual and civil power was

never as neat and clear-cut as this would suggest. Luther himself intervened ceaselessly in matters that might properly be regarded as political. In Wittenberg he acted as an informal court of appeal for those who had fallen foul of the law or who appealed to Luther to help secure justice. Luther was happy to make representations in such cases to the electoral authorities.

3

Most of these appeals were granted. So numerous indeed were Luther’s interventions in such cases that in 1532 the young elector John Frederick was obliged to warn Luther that he might not be able personally to read them all, as had apparently been his father’s practice.