Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (20 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

One such was

The Treatise on Good Works;

among all the mass of texts that Luther penned during these years he himself regarded it as the best thing he had written.

4

Once again the initiative came from Spalatin, though when Luther began it he apparently intended nothing more than the preparation of a sermon for his Wittenberg congregation. In the event the task took him two months, and the brief homily became a substantial and fundamental work. Luther’s intention was to spell out clearly, for a lay audience, the practical implications of his rejection of good works as a means to earn salvation. Luther set out the alternative with his usual uncompromising clarity: “the first and highest, the most precious of all good works is faith in Christ.”

Note for yourself, then, how far apart these two are: keeping the first Commandment with outward works only, and keeping it with inward trust. For the last makes true, living children of God, the

other only makes worse idolatry and the most mischievous hypocrites on earth.

Here Luther sanctified the faithfulness of the everyday, the dutiful performance of the obligations of one’s calling, as opposed to what he called self-elected work, such as “running to the convent, singing, reading . . . founding and ornamenting churches . . . going to Rome and to the saints, curtsying and bowing the knee.” The search for God’s purpose in the everyday was the human healing consequence of justification by faith, the theology of salvation that Luther would expound in its definitive form later in the year in

The Freedom of a Christian Man

.

The dedication of

The Treatise on Good Works,

to the elector’s brother and heir, Duke John, also contains a short but moving defense of Luther’s vocation as a vernacular writer.

And although I know full well and hear every day that many people think little of me and say that I only write little pamphlets and sermons in German for the uneducated laity, I do not let that stop me. Would to God that in my lifetime I had, to my fullest ability, helped one layman to be better! I would be quite satisfied, thank God, and quite willing then to let all my little books perish. Whether the making of many large books is an art and of benefit to Christendom, I leave for others to judge. But I believe that if I were of a mind to write big books of their kind, I could perhaps, with God’s help, do it more readily than they could write my kind of little discourse.

I will most gladly leave to anybody else the glory of greater things. I will not be ashamed in the slightest to preach to the uneducated layman and write for him in German. Although I may have little skill at it myself, it seems to me that if we had hitherto busied ourselves in this very task and were of a mind to do more of it in the future, Christendom would have reaped no small advantage

and would have been more benefitted by this than by those heavy, weight tomes and those

questiones

which are only handled in the schools among learned schoolsmen.

5

The reading public obviously agreed.

The Treatise on Good Works

was an immediate success, with four editions from Melchior Lotter before the end of the year, and reprints in Augsburg, Nuremberg, Basel, and Hagenau. Luther’s

Sermon on the Mass,

tutoring the laity on another key aspect of his new theology, went through ten editions in 1520 alone.

6

If we are seeking an explanation of why so many Germans were drawn to Luther, despite the wild, extravagant denunciations of the established church and the bitter, angry polemic against his critics, we have to recognize that this was not the Luther that many readers saw. Rather they embraced the patient, gentle expositor whose explorations of the Christian life offered them comfort and peace.

DUE PROCESS

At the Leipzig Disputation both parties had agreed that formal judgment should be rendered by the universities of Paris and Erfurt. Neither university viewed this charge with any great enthusiasm. Erfurt would eventually decline to take a position, while Paris delayed a response for two years, by which point events had moved on. It was left to others to fill the void, informed not only by the protocols of the disputation, but by the rancid charge and countercharge of the ensuing pamphlet war. On August 30, 1519, the University of Cologne issued a public proclamation condemning a number of teachings found in Luther’s works. The basis of this condemnation seems to have been the second collective edition of Luther’s works, published in Strasbourg on the basis of Froben’s Basel prototype.

7

The Cologne articles were then delivered to the Faculty of Theology of the University of Louvain, who in November issued their own judgment. These statements, from two distinguished

institutions somewhat removed from the partisan hurly-burly of Erfurt and Leipzig, were important and influential, and played a critical role in marshaling conservative opinion against Luther. The published texts of these judgments would also guide the renewed deliberations of Luther’s cause in Rome.

A published version of the universities’ judgments was soon in Luther’s hands, and he fired off a reply.

8

He also engaged in a polemical exchange with the bishop of Meissen, who had taken up the cudgels on behalf of Duke George, the host of the Leipzig Disputation and now emerging as a dogged defender of the established way. Clearly, though, resolution of the matter required a definitive verdict from Rome, where the initially swift engagement with Luther’s heresy had been hopelessly sidetracked by the complex politics of the Empire in 1519. In January 1520 the process against Luther was formally reopened. Even now the required sense of urgency seemed decidedly lacking. Commissions were formed, dissolved, and reconstituted. It was only with the arrival of Johann Eck, summoned by Pope Leo as the acknowledged champion of orthodoxy and Luther expert, that matters moved forward. In May 1520 Eck had prepared a draft for discussion in consistory, and in June this was finally issued as the papal bull

Exsurge Domine

. The bull, like all such documents, took its name from the first words of the text: in this case the words of the psalmist, “Arise, oh Lord, and judge thy own cause.”

This was very much Eck’s document, a much more comprehensive condemnation of Luther’s teaching than had been favored by others in the Curia. It ranged far beyond the original issue of indulgences, with forty-one articles of condemnation drawn from the whole range of Luther’s writings. It declared Luther to be in error in the matter of penance, the Lord’s Supper, excommunication, the power of the pope, good works, free will, and purgatory. It was a manifesto of Luther’s movement in reverse. If not recanted, all of the errors listed here would bring Luther, his allies, and his protectors under the penalties of excommunication and interdict. It was a hugely influential statement of where the church would stand in all the major issues of doctrine, church practice,

and government raised by Luther in the escalating conflict, anticipating many of the doctrinal positions affirmed by the Council of Trent forty years later.

The bull was also a legal document, and formally at least held out the hope of repentance and reconciliation. Luther was allowed sixty days to signal his return to obedience, this grace period to begin at the point when the bull had been formally posted on the cathedral doors in Rome and the three local German dioceses of Brandenburg, Meissen, and Merseburg. The honor of formally serving this document was given to Johann Eck. This proved to be a far more difficult assignment than marshaling the commission in Rome. Eck’s return to Germany was anything but triumphant. The posting of the bull in Rome had been accompanied by a burning of Luther’s books, but an attempt to replicate this ceremony in Mainz caused such public anger that the town executioner abandoned the task. In Leipzig Eck was greeted with mocking satirical verses and forced to take refuge in the monastery of St. Paul. He left without having accomplished his task; when the university did, on Duke George’s insistence, post the bull, it was smeared with mud and defaced. This was also the case elsewhere in the vicinity, such as Torgau; in Erfurt students tossed copies of the bull into the river.

9

Although Eck did, through various means, succeed in distributing the bull as its terms stipulated to the major cathedrals, not a single copy of the original broadsheet version—the version that would have been posted in this way—has so far been traced today.

10

In many jurisdictions the local church authorities preferred to avoid public disturbances by delaying publication, or avoiding it altogether.

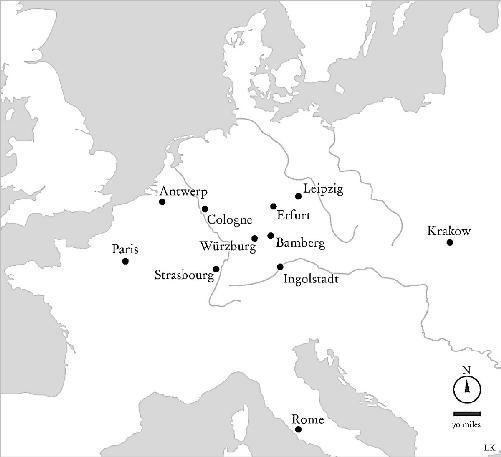

With the formal promulgation of the bull so comprehensively disrupted it was left to Germany’s printers to fill the gap. In addition to the official broadsheet version of the bull it had, like Luther’s ninety-five theses, also been issued as a pamphlet, and this became a European best seller. The original Rome version was reprinted in Paris, Antwerp, and Krakow. In Germany it was printed in the loyally Catholic jurisdictions of Cologne, Ingolstadt, Würzburg, and Bamberg.

11

These were not places where Luther’s works had been extensively printed, but the bull was also published in places that had eagerly embraced Luther, like Leipzig, Erfurt, and Strasbourg. Once again printers were happy to hedge their bets. Johann Schott of Strasbourg published the papal bull a matter of weeks after he had enjoyed a runaway success with Luther’s

Babylonian Captivity

. His colleague Johann Prüss published both the bull and Luther’s

Freedom of a Christian Man

. The Leipzig edition was published by Martin Landsberg, a printer with a long-established Wittenberg connection.

12

P

UBLISHED

E

DITIONS OF

EXSURGE DOMINE

Of course, there was every reason why Germans would have wanted to see this text, whether they sympathized with Luther or his opponents. Many even of those who deplored Luther’s uncompromising positions were still, like Erasmus, made uneasy by the sweeping nature of the

bull’s condemnations. Others were simply curious. It is notable that in addition to the dozen pamphlet versions of

Exsurge Domine,

there were also at least two editions in German: an Ingolstadt edition in a translation supplied by Johann Eck, and another published by Peter Quentel in Cologne.

13

This represented a significant change in strategy, quite possibly conceived on Eck’s own initiative. While in Rome it seems still to have been preferred to treat Luther’s case as a judicial matter, to be settled according to the church’s established procedures, in Germany at least there was a dawning recognition that it would be necessary to fight fire with fire.

Luther’s own response was not slow in coming. He was aware of the bull’s main provisions long before a copy reached him, through several pairs of hands, in Wittenberg on October 10. The rector of the university would protest at this irregular delivery “in a thieving manner and with villainous cunning,” but Eck’s reluctance to send his own messenger to Wittenberg is understandable, given its reception elsewhere. Luther’s first reaction was to treat the bull as a personal concoction of Eck, and he taunted his opponent for his failure to deliver it personally. He followed the same line in a Latin pamphlet,

Against the

Execrable Bull of Antichrist,

also published in a German version.

14

These partisan efforts served to rally supporters, but they were clearly not sufficient. In December 1520, and at the urging of Frederick the Wise, Luther penned a more substantial and considered defense of the articles condemned in the bull.

15

But with the delivery of the bull to Wittenberg the clock was ticking on the sixty-day grace period for Luther’s formal response to Rome. For this he planned a more dramatic gesture.

MANIFESTOS

The extraordinary dramas and tensions of these months had kept much of Germany transfixed: from the frantic local conflicts that erupted around the posting of the bull, to the urgent private political discussions

where Luther’s fate was debated and bargained over. Yet somehow, amidst all this sound and fury, Luther found the energy and mental space to compose the three great works that have come to define his movement. These three writings were

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,

The Babylonian Captivity of the Church,

and

The Freedom of a Christian Man

. Although sometimes considered as three components of a program or agenda, they were, in fact, very different, all responding, as was Luther’s way, to different aspects of the situation in which he found himself: the complex problems of authority and jurisdiction; the profound implications of his soured relationship with the church hierarchy; and the fundamental theological reflections on which Luther based his new understanding of the Christian relationship with a merciful God.