Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (24 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Engaging this new public would ultimately be hugely lucrative for Germany’s printers, but the challenges of this expanding market were not insignificant. Capturing new readers required both ingenuity and innovation: a new movement required a new sort of book. In mastering these design challenges, Germany’s printers gradually settled on a look that was distinctive and instantly recognizable. This was Brand Luther, and it was one of the great unsung achievements of the Reformation.

THE TECHNOLOGY OF IMITATION

The first of Luther’s works published in Wittenberg were in design terms very little different from what Rhau-Grunenberg had published in the previous ten years. Examining these books, potential purchasers would certainly not have known that something extraordinary was afoot. This was Rhau-Grunenberg’s way. Although an educated man, he was something of a printing novice when he came to Wittenberg. His apprenticeship in Erfurt was brief, and he had absorbed none of the more sophisticated working practice of the larger Erfurt houses. Nor did he show any inclination to change an established formula.

It quickly became clear that the demand unleashed by the Reformation had overwhelmed Rhau-Grunenberg’s little shop. Luther grumbled that he was slow and inaccurate; but it was also the case that the new money flowing into the shop from sales did not inspire him to the reinvestment that could have transformed the look of his books. A tract published for Andreas von Karlstadt in 1518 still looked exactly like something

he might have produced for a student’s dissertation defense when he first became the university printer.

4

Something clearly had to change.

The first hint that the Reformation could offer something better came when Luther’s works were taken up in Germany’s larger printing centers. The pamphlet version of the ninety-five theses published by Adam Petri in Basel is a quite beautiful piece of work.

5

The text is spread through eight quarto pages, in neatly balanced groups of twenty-five and twenty. The numeration is crisply aligned in the margin. Careful use is made of indentation to distinguish the separate theses. The use of white space to guide the eye is elegant. So, too, is the woodcut initial at the head of the texts. (As we have seen, Rhau-Grunenberg seems not to have equipped himself with a set of these larger initials.)

The chain of connection between Basel and Wittenberg ran through Leipzig and Augsburg. Leipzig, rather fortuitously, was at this time the largest center of book production in Germany. Its long established and experienced printing houses employed a far greater range of typefaces than Rhau-Grunenberg. Early Leipzig reprints of Rhau-Grunenberg’s work offered a master class in how different fonts of type could be used to differentiate text and supporting matter, side notes, and references. Melchior Lotter Senior, one of the first to print Luther in Leipzig, also used decorative blocks to create a border surrounding the text of the title page.

6

This was a useful way of drawing the customer’s eye to a particular item laid out on the bookseller’s stall, though not particularly new: we see the same framing device in editions of the sermons of Savonarola published in Florence in the last decade of the fifteenth century. Augsburg printers also contributed early Luther editions of great elegance and professional competence. Augsburg was unusual in the history of printing, in that almost from the beginning of print, vernacular, rather than Latin works, had dominated its output.

7

This long experience in the publication of German-language works was now put to the service of Luther’s movement.

Luther would have been aware of the vast superiority of the editions of his works published elsewhere in Germany, not least from copies sent

back to him by friends or grateful printers. We know that when Johann Froben of Basel wrote to Luther in 1518 to inform him of the success of the anthology of his works, he enclosed a copy of this volume, and some volumes of Erasmus.

8

Luther would also have had opportunities to examine the books published in Augsburg, Leipzig, and Nuremberg during his various trips out of Wittenberg in the years 1518 and 1519. The Wittenberg University library also contained examples of some of the best workmanship available in the European book world, thanks not least to the elector’s assiduous courtship of Aldus Manutius.

9

Martin Luther was a man of refined aesthetic sensibility. He knew that the books published in Rhau-Grunenberg’s shop hardly did Wittenberg justice. He complained early and often of the quality of the workmanship, the frequency of errors, the slow pace of production. Persuading Melchior Lotter to send his son to Wittenberg was an important step toward remedying this situation.

10

Melchior Junior turned out to be extremely able. He brought to Wittenberg the efficiency and competence of his father’s well-capitalized print shop; he also had access to a wide range of his father’s types.

The look of Wittenberg Luther editions improved immeasurably. Here we see what was becoming quite distinctive of the Reformation

Flugschriften,

the vernacular pamphlets published in Leipzig, Augsburg, Basel, and now also Strasbourg. All would be in the quarto format used for most everyday publishing in Germany.

11

They were usually very short, eight or sixteen pages, which would have been one or two sheets of paper, printed and then folded into four (hence quarto). Using so little paper, they were always very cheap. Customers took to purchasing large numbers, which they then bound together in impromptu anthologies (which is how many of them have come down to us). These

Flugschriften

usually had a neat, orderly title page, spelling out the subject and in Luther’s case naming the author. This was important, for it was not universally the case that the title page would include the author’s name (particularly if the author was a living person, rather than one of the great classical or medieval authorities). In Luther’s case his name would

appear, since he was an important selling point. The title page would also, as in Melchior Lotter’s examples, often make use of decorative woodblocks to encase the text.

The printer’s world was very much one of imitation and shameless borrowing; when printers saw that a trade rival had adopted a new feature that seemed to work, they would simply incorporate that feature into their own work. In this way there gradually emerged the features that we associate with the Reformation pamphlets, and we see these replicated in many hundreds of individual titles. Wittenberg was now able to play a full part in this trade. But what Melchior Lotter brought to Wittenberg was essentially the proficiency and style of Leipzig; indeed, his works are stylistically quite close to works published in his father’s shop, still fully operative in Leipzig. There was nothing very distinctive to Wittenberg about these books. To create a specific Wittenberg style, the city’s printers had to make use of their greatest latent asset. For Augsburg and Leipzig might have had greater capital resources, the longer printing heritage, and the better-established print shops. But Wittenberg had Lucas Cranach.

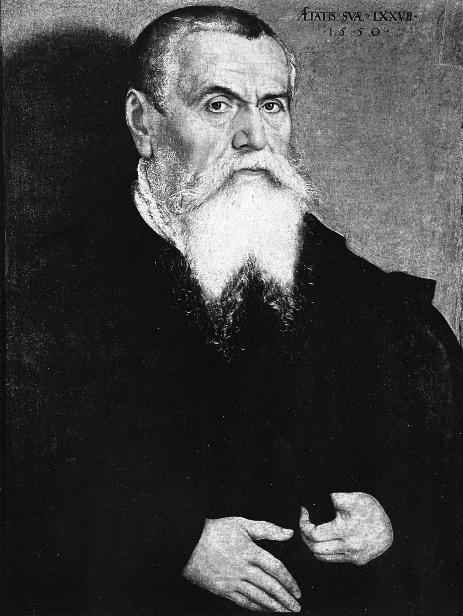

LUCAS

Cranach was born Lucas Maler (Painter), in the small Franconian town of Kronach, midway between Erfurt and Nuremberg.

12

As the name suggests, his father also worked in the trade that would make his son famous. Young Lucas’s artistic education took place in southern Germany and Vienna. Of the major German painters of this period, Cranach was the most prominent never to have visited Italy. What he imbibed of the Italian Renaissance was learned at second hand, from studying the works of others and especially Albrecht Dürer, the yardstick against which all artists of the northern Renaissance have been measured, then and now. But Cranach remained very much his own man. A master technician, his work remained quintessentially German, without the self-conscious

obeisance to Italian style characteristic of celebrated contemporaries. This is most obvious in his depictions of the human form, and in the magnificent landscapes in which many of his works are framed.

L

UCAS

C

RANACH

One of Luther’s closest allies in the Wittenberg elite, Cranach would play a crucial role in presenting Luther to the wider world. He also played an instrumental role in the Wittenberg publishing industry.

Cranach was already a mature force of established reputation when he joined other distinguished contemporaries in Wittenberg, to work on the decoration of Frederick’s mammoth building projects. But whereas Dürer and others came and went, Lucas was content to remain in Saxony; in 1505 he succeeded the Venetian Jacopo de’ Barbari as Frederick’s court painter. This was a role that called above all for versatility. Cranach

was obliged to turn his hand to anything that took the elector’s fancy: religious art, portraits, hunting scenes, or wall painting. He orchestrated court festivities and the necessary banners and decorations; on one occasion he even designed a nut grater for the elector’s young nephews.

13

These multiple assignments taught Cranach efficiency in the dispatch of work, a skill that would come to characterize his whole career. Cranach was an exceptionally effective manager and an astute businessman; he also worked extremely quickly. He was already famous among contemporaries for this speedy painting style, a pragmatism that has not always found favor with the more fastidious modern connoisseurs.

His new patron was evidently delighted with Cranach’s work. For his diverse responsibilities Lucas was well rewarded. He received a salary of one hundred gulden a year, double that of his Venetian predecessor.

14

He was also given a horse and an apartment in the castle. All his artistic materials were paid for separately. Crucially, although his responsibilities to the elector took priority, Lucas was also free to take on work for other patrons. Since he was by far the most distinguished painter in northeastern Germany, these commissions came in a steady flow, and Cranach continued to take on work for a large variety of institutions and individuals throughout the rest of his long life.

In contrast to Martin Luther, who scarcely ever came into the elector’s presence, Cranach’s relationship with his patron was close. In 1508 Frederick may have raised some eyebrows by granting his relatively lowborn court painter a coat of arms. This same year Cranach was dispatched to represent the elector on a diplomatic mission to the Low Countries. The ambassadors had been sent to negotiate a marriage alliance between the imperial house and the elector’s own family. Although this did not materialize, Cranach was able to immerse himself in the extraordinary achievement of the Flemish artists on this trip. This was his first major sortie out of the Germanic lands, and it would not be repeated.

During these early years in Wittenberg, Cranach had also mastered the art of the woodcut. Woodcuts—where the image was carved into a

block of wood, from which a printed impression could be taken—played an important role in the book industry. The woodcut could be laid on the platen alongside text, and then printed off in the same impression. This was not the case with engraving, another illustrative technique beginning to make its mark, since the metal engraved plate had to be passed through a different, cylindrical press. This meant that combining engraving and text in moveable type on a single sheet required the paper to be passed through two separate presses, and careful alignment; the insertion of woodcuts into a page of type posed no such complexities. Woodcuts were by this point heavily used for decorative material, such as initial letters and bordering, for playing cards and for illustrations, printed either separately on broadsheets or on the pages of books.

It was in Germany, and precisely in these years, that the art of the woodcut reached its peak.

15

In the years before the Reformation the woodcut form found its most refined expression in the great Passion series of Albrecht Dürer, but Cranach’s series of fourteen woodcuts on the same theme (1509–1511) certainly bears comparison.

16

Cranach was also required to undertake more mundane tasks in this genre, such as the more than one hundred illustrations required for the published catalog of Frederick’s great relic collection.

17

With so many and varied responsibilities, Cranach was by this time of necessity a major employer. Between 1510 and 1512 he shifted his operations from the increasingly cramped quarters in the castle to a new site in the center of town. Here, after massive building works that lasted the best part of a decade, he would gradually create a vast artistic factory, a workshop on the scale we associate with the greatest of the northern artistic entrepreneurs, Peter Paul Rubens or Rembrandt. At Schloβstrasse 1 Cranach presided over the production of artistic work in industrial quantities. We know of one order, from 1532, for sixty paired portraits of the elector, John the Constant, and his late brother, Frederick the Wise.

18

These were manufactured in the workshop by a small army of assistants, for the elector to distribute to favored citizens and foreign dignitaries. The iconic portraits of Luther, of Luther and his wife, Katharina, or of Luther and Melanchthon, were

manufactured in similar quantities.

19

Not all of these workshop pieces were of the highest quality, but they played an important role in building the iconography of the Reformation.