Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (28 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

The bond with Luther was forged at the time of the Diet of Worms. When Luther made his triumphant approach to Erfurt on his way to the Diet, Jonas rode as far as Weimar to greet him, and traveled on with his other companions. At Worms he met Cochlaeus, who described him, generously in the light of their later history, as “an excellent young man, of tall stature and very cultivated.”

13

Within a month of his return to Erfurt Jonas had been appointed to a position in Wittenberg, where he would remain to the end of his life.

Jonas was quickly integrated into Luther’s inner circle. He was promoted to a doctorate in theology in 1521 and served both as dean of the Theology Faculty and rector of the university. He was one of the first of Luther’s intimates to marry. But he was no Philip Melanchthon; though he engaged gamely in the polemical controversies, and thus earned the ire of Cochlaeus, his principal service was as the editor and translator of the works of others. He was responsible for a fine, free translation of Luther’s

De Servo Arbitrio,

and also translated both Melanchthon’s

Loci Communes

and his

Apologia

for the Augsburg Confession. But Jonas was also his own man. His transfer to Wittenberg from Erfurt was delayed by his reluctance to take on his originally prescribed duties (Jonas was

intended to teach Canon Law) and he retained a loyal affection for Erasmus long after it was politic to do so. This was sufficiently public that Luther chose to refer to this rather pointedly in print: “My dear Dr. Justus Jonas would not leave me in peace and kept urging me to deal sincerely with Erasmus and to write against him with due reverence. ‘Doctor, sir,’ he said to me, ‘you have no idea what a noble and reverend old man he is.’” This very public prompt clearly had the desired effect. Later that same year Luther could write to Jonas, “I congratulate you on your recantation. Finally you depict Erasmus in his proper colors, as a deadly viper full of stings. Before that, you honored him with many complimentary epithets, but now you recognize his true nature.”

14

In Luther’s Wittenberg it was ultimately not possible to serve two masters.

J

USTUS

J

ONAS

T

RANSLATING

L

UTHER

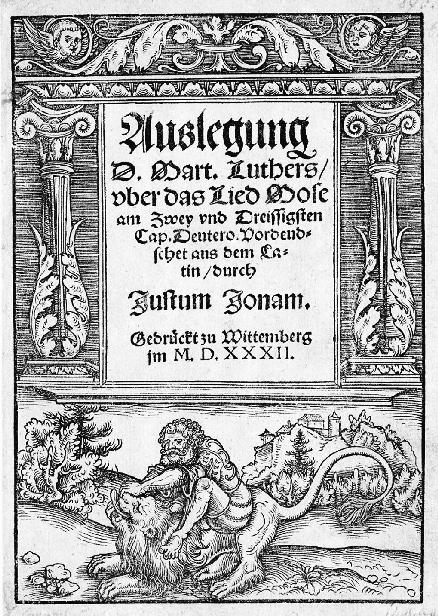

Although Jonas was a dutiful participant in the Reformation’s polemical debates, his main service to the Reformation was as an editor and translator. This translation of Luther was published with a superb Cranach title page (Samson and the lion).

Johannes Bugenhagen came to Luther’s circle by a rather different route. Born in Wolin, a Baltic island off the Pomeranian coast, and educated at the University of Greifswald, Bugenhagen first became acquainted with Luther’s teachings when the reformer’s works began to circulate locally. In 1520 Bugenhagen came across a copy of Luther’s

Babylonian Captivity

in the house of a friend, who asked Bugenhagen his opinion. Like many, Bugenhagen was first repelled by its radicalism. According to a later authority his first reaction was uncompromisingly negative: “There have been many heretics since Christ’s death, but no greater heretic has ever lived than the one who has written this book.” But he was also fascinated, and asked his friend for the loan of the book to peruse it more carefully. This study made him a disciple. “What shall I say to you?” he told his friend a few days later. “The whole world lies in complete blindness, but this man alone sees the truth.”

15

Bugenhagen now contacted Luther directly and asked for guidance. Luther sent an encouraging letter along with a copy of his

Freedom

of a Christian Man

. That was enough. In the spring of 1521 Bugenhagen left Treptow for Wittenberg.

Bugenhagen’s initial intention was to study, so he enrolled as a student in the university (a rather mature one, since he was now thirty-two). But he was soon in demand as a teacher, initially to younger

students from his native Pomerania, to whom he offered a lecture course on the Psalms. One of the first to recognize Bugenhagen as a special talent was Philip Melanchthon, who had dropped in to sample these private lectures and encouraged Bugenhagen to continue the course in public. Bugenhagen thus became an unofficial member of the university faculty, though this status was only officially recognized in 1533 once he had received his doctorate.

Luther was also quick to recognize Bugenhagen’s qualities. He earned Luther’s respect by his firm support of restraint and order during the turmoil unleashed by Karlstadt and the Zwickau prophets while Luther was absent in the Wartburg. In 1522 he took a further decisive step by taking a wife. This was not without a certain degree of emotional trauma, since his first choice of spouse got cold feet and called off the engagement: in 1522 to enter into marriage with an evangelical minister was still a difficult choice for a young woman of respectable family. But in October Bugenhagen married the excellent Walpurga, a spirited and practical-minded life partner who would be a constant support for Johannes in all of his future endeavors. With these extra responsibilities Bugenhagen was now urgently in need of a settled income; the problem was simply solved with his appointment as minister to the local parish church.

Here he would be both Luther’s colleague and his pastor, responsible for ministering to the reformer’s spiritual needs. This would be the basis of a lifelong and trusting friendship. When Bugenhagen’s

Commentary on the Psalms,

the fruits of his early Wittenberg lectures, was published in 1524, it included commendatory recommendations from both Luther and Melanchthon. Luther’s preface spoke eloquently of both their friendship and his regard for his colleague’s talent. Instead of waiting on Luther’s own long-delayed Psalm commentary, the reader should rejoice in Bugenhagen’s work: “I make bold to say that no one (of those whose books survive) has ever expounded David’s Psalter in such a way as to be called an interpreter of the Psalter, and that [Bugenhagen] is the first man in the world to deserve that title.”

16

Praise indeed.

This Psalm commentary, published in a fine edition in Basel, was the first of a considerable sequence, which took in expository works on Deuteronomy, the historical books of the Old Testament, and the Pauline Epistles. Fine theologian though Bugenhagen was, however, his principal service to the Reformation would be as a church organizer. In 1524 the congregation of the Church of St. Nicholas in Hamburg wrote to invite Bugenhagen to be their pastor.

17

This was obstructed by the Hamburg City Council, and a similar call from Danzig (Gdansk) in 1525 was declined because the Wittenberg congregation refused to release him. But the requests for Bugenhagen’s services continued: he was especially in demand when cities and princely territories wished to make the decisive step and adopt an evangelical church settlement. For this important purpose his Wittenberg colleagues were prepared to release him, even if this meant Luther had to shoulder many of Bugenhagen’s preaching duties in the Wittenberg parish church. In 1528 Bugenhagen was allowed to make an extended trip to assist the city of Braunschweig in organizing the local church. This resulted in the drafting of the first of a series of highly influential church orders, for Hamburg and Lübeck, later for his own native Pomerania (1534) and Schleswig-Holstein (1542). Bugenhagen also led the way in his emphasis on the importance of well-organized and regulated schools; he was also one of the few in Luther’s inner circle who spoke and wrote the language of the north, Low German. He translated Luther’s

Catechism

into Low German, and also played a leading role in the preparation of the first Low German edition of the Luther Bible.

Luther could be a difficult and demanding friend. But to those in his inner circle he was loyal and supportive, in public and private. Cochlaeus’s identification of the four evangelists as the core of the Wittenberg movement thus struck at an essential truth: that as the Luther controversy moved from protest to movement, Luther could not be a man alone. This applied not only to his closest workmates, and to the younger men who flocked to hear him and hung on his every word at the family supper table. Luther also grasped the role that the medium of print

could play in building and publicly proclaiming this new community of evangelical truth.

A HELPING HAND

We have seen how shrewdly Luther intervened to build the printing industry in Wittenberg, drawing to the city an experienced printer to assist the overburdened and unimaginative Rhau-Grunenberg keep up with demand for his works. He was impatient with what he regarded as shoddy work, as the angry stream of letters from the Wartburg bears witness.

18

Wittenberg printers must have found him a demanding presence as he scrutinized their workmanship. But there was also a very positive side to Luther’s mastery of the technical demands of the trade. He was sufficiently well versed in these practical considerations to be able to accommodate his own work to its rhythms and timetables, and he took a close interest in the process by which his manuscripts made their way into printed form.

Luther also understood his own importance to the Reformation’s extraordinary success. However he might muse in his letters and sermons on his role as the humble instrument of God’s purpose, he was fully aware that his own personality and the drama of his struggle with the church authorities was what had piqued public interest and furnished the movement with its most powerful shield against those who would destroy it. There is a fascinating little vignette in an otherwise routine letter to Spalatin in early March 1521, while Luther was awaiting his summons to the Diet of Worms. With this letter he enclosed some copies of Cranach’s early engraved portrait of himself, which at Cranach’s request he had also autographed.

19

The signed portrait as gift is something we associate with modern celebrity culture, to be displayed by the honored recipient as a token of acquaintance with leading statesmen, actors, or musical artists. It is curious to find Luther already engaged in something similar.

This is not the only way in which Luther exploited his fame to build the movement. In the published works of the Reformation, Luther also lent his prestige to works written by others by furnishing a brief preface or recommendation. These celebrity endorsements offered a seal of approval for a writing campaign that was self-evidently increasingly a team effort.

As with so much in the dramas of the Reformation, this program of prefatory endorsements began somewhat accidentally. Already in 1521 Luther was concerned at the increasing burden of answering his Catholic critics. Particularly irksome was the indefatigable secretary of Duke George of Saxony, Jerome Emser, who had kept up a fairly constant barrage since the Leipzig Disputation. When Emser published his

Quadruplica,

a further riposte to Luther’s

Answer to the Book of the Goat Emser,

Luther had had enough. “I shall not answer Emser,” he wrote to Melanchthon. “Anyone who seems fitting to you may answer, perhaps Amsdorf, if he is not too good for dealing with this dung.”

20

To Amsdorf he apologized for shuffling off this unwelcome burden, though he was already beginning to have second thoughts.

Philip wrote that you intend to answer Emser, if it seems wise to me. But I am afraid that he is not worthy of having you as a respondent. On the other hand he may laugh and mock if one of the young people should answer him, since he is full of Satan.

21

Here lay the dilemma. Luther did not want to dignify his opponent’s efforts with a response. On the other hand a reply by an inexperienced or callow disputant might hand the Romanists a propaganda victory, a lesson Luther had learned from Andreas von Karlstadt’s enthusiastic but not always well-judged interventions in his cause. In the event, on this occasion Luther bit the bullet and replied himself, but from this point he was always happy when one of his more experienced colleagues would share the burdens of the print exchanges.

In 1522 Luther’s

Judgment on Monastic Vows

unleashed a storm of

protest from conservatives, particularly those themselves in holy orders. Among those who wrote against him was the Bavarian Franciscan Caspar Schatzgeyer. On this occasion Luther felt that Schatzgeyer, a relatively obscure figure, could be left to a friend, and he commissioned Johann Briesmann to undertake the task. This was a shrewd choice. Briesmann was well-known to the Wittenbergers, having served briefly on the university faculty before returning to his native Cottbus to pursue the task of reform in Brandenburg. As a former Franciscan, Briesmann was also able to take on Schatzgeyer on his own ground. In this instance Luther’s preface was clearly written before the main text, since Luther laid out the agenda he hoped Briesmann would follow fairly fully.

22

This was one of the longer prefaces; on other occasions Luther would write no more than a few paragraphs, praising the author and signaling his approval of the contents.