Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (48 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

This then was a complicated ceremony of confected memory and genuine theology, of affectionate allusive recollection of the founding father and dogged incantation of familiar foes. As 1617 drew to a close it was hard to deny that the jubilee had been an enormous success, engaging the curiosity and enthusiasm of Protestant communities across the

Empire. This was now an established church; some of those involved would have been the grandchildren of those who had first taken the momentous step outside their historic Catholic allegiance. But as the Lutheran congregations processed, sang, and clinked their newly minted medals, it was easy to forget that this act of commemoration was equally an act of forgetting. Forgetting the storm clouds that loomed over Germany and would within a year plunge it back into a long and destructive war that at times seemed once again to threaten the survival of Luther’s church. Conveniently ignoring the fact that the driving force behind these events was not the established leaders of German Lutheranism but the Elector Palatine, a committed Calvinist. Most of all, casting a veil over two generations of poisonous contention within the Lutheran family, of

friendships severed, of feverish pamphlet battles, and even of occasions when fellow Lutherans were pursued to their death, all to claim the right to interpret the meaning of Luther’s great movement.

This, too, was part of his legacy. It meant that even after Luther’s death the battle of the books could not be stilled. The struggle for Luther’s posthumous approval continued to consume his followers and provided for Germany’s printers a steady stream of work to the end of the century and beyond. In other parts of Europe during these decades, France and the Low Countries for example, wars of religion stimulated a new surge of pamphlet publications reminiscent of Germany in the 1520s. The situation in Luther’s homeland was rather different. Here the output of the presses was much more diverse, reflecting the needs of a church still troubled by new challenges, but essentially fixed and settled. Now there were churches to be built, ministers to be trained, a Christian people to be educated, enemies, old and new, to be confuted. All provided work to keep the presses rolling. Print, it transpired, was not just an instrument of agitation and change: now it was equally necessary to win the peace and shape the new churches of the Gospel preaching.

THE WAY OF THE CROSS

On April 24, 1547, fourteen months after Luther’s death, the forces of the Schmalkaldic League came face-to-face with Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg. The printer Georg Rhau was also there with his field press, ready to convey to the world the news of the anticipated Protestant victory. Alas for Rhau, alas indeed for the Protestant princes, the battle would take a very different course. The league’s forces were routed and Charles emerged triumphant. Among his prisoners were the leaders of the Protestant resistance, Elector John Frederick and Philip of Hesse—along with Rhau and his press. Wittenberg and Electoral Saxony now lay defenseless before the victorious imperial army.

The emperor moved quickly to exploit his triumph. John Frederick

was hustled off into captivity, emerging only five years later, condemned, and stripped of his electoral title and much of his territory. From Wittenberg, Lucas Cranach, now an old man in his seventies, journeyed to the imperial camp to plead for the elector’s life; he later joined his master in the last stage of his captivity.

8

His workshop was left in the more than capable hands of his son Lucas Junior. Wittenberg was besieged and then occupied. According to tradition, one of the emperor’s first actions on entering the occupied city was to visit Luther’s grave in the castle church. Twenty-six years earlier Luther had slipped through Charles’s fingers at Worms. Now he had evaded him in death.

For all that, some sort of retribution, however symbolic, might have been in order. Luther had died a condemned heretic and outlaw. Custom and legal practice might have suggested that the appropriate penalties should have been visited on his corpse. Ten years later the government of Mary Tudor would do precisely this with the remains of the Strasbourg reformer Martin Bucer, who had died in England; a century later similar indignities were visited on Oliver Cromwell’s remains by Charles II. Shrewdly, the emperor denied himself the satisfaction. At Worms he had let Luther depart because he had promised to do so to conciliate the Protestant princes. Now he had similar policy objectives in mind. Why outrage Protestant opinion when he hoped to enforce on his defeated enemies a settlement of religion that at least some of them could accept? His partial success in this endeavor would come close to ripping Luther’s church apart.

In the existential crisis after Mühlberg, German Lutheranism looked for leadership to Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s closest friend and intellectual companion. This, alas, was a role for which Philip was singularly unsuited. His true vocation was that of the scholar and theologian; as a church politician, or even as the leader of a church (as the months of Luther’s absence in the Wartburg had proved long ago), he was totally at sea. Stunned and still grieving from the loss of his friend, Melanchthon was forced into a series of compromises that badly divided and scarred the movement; never was the church more in need of Luther’s brutal

clarity and stubborn immovability than in these desperate years after his death.

In 1546, as the contending armies approached Saxony, Wittenberg University had been temporarily dissolved. Melanchthon fled with his family to Zerbst. With the war concluded, Wittenberg, now a town under occupation, was passed to Maurice of Saxony along with the electoral title as a part of his reward for allying with the emperor against his cousin and the Schmalkaldic League. Faced with the fallout from this dynastic pragmatism, Maurice was keen to reestablish his Protestant credentials and to woo the absent professors back to a restored Wittenberg University. This faced Philip with a difficult decision. Should he return, and seem to endorse the passage of power to a man who had abandoned his Protestant brethren for short-term gain? Melanchthon was already aware that the three sons of the imprisoned John Frederick were hatching plans for a new alternative university at Jena, in the small residual territory left to the defeated Ernestine line; but it might be many years before anything came of this (and indeed, the university only opened its doors in 1558). Philip, with hesitation and reluctance, opted to return home.

Worse was to come. In 1548 the emperor, as expected, moved to impose a new settlement of religion on German Protestantism. This, the Augsburg Interim, would have involved the reinstatement of many aspects of traditional religion. The Interim was immediately condemned by the Lutherans of northern Germany, safely removed, it must be said, from the conquering imperial army. The Interim was also unpalatable to Maurice, a committed Lutheran when all was said and done. He requested that Melanchthon confer with colleagues to see what could be conceded to the victorious emperor without compromising the essentials of faith. In an exhaustive series of meetings through the summer and autumn of 1548 Melanchthon was gradually brought to moderate his initially emphatic repudiation of the Interim. Comforting himself that he salvaged the principal theological tenet of the church, justification by faith, Melanchthon acknowledged that it was legitimate for the

state power to regulate church practice with respect to ceremony and church order—matters of custom and practice, nonessentials or adiaphora. For many Lutherans, the messy document in which Melanchthon articulated this complex formula, which became known as the Leipzig Proposal, was the ultimate betrayal. Could such “trifles” as holy water, censing, the Consecration of the bread, or unction at baptism be regarded as adiaphora, was the sarcastic inquiry of the Berlin theologians.

9

And could the church really tolerate the reimposition of Catholic Church structures, including the authority of bishops?

Melanchthon’s acceptance of the Interim, for all his qualifications and mental reservations, was a turning point for the movement. For the first time Wittenberg’s leadership of Luther’s movement was called into question. While old colleagues like Bugenhagen stayed loyal, others in the inner circle now separated themselves from Melanchthon, including Luther’s old companion in arms Nicolas von Amsdorf. These dissidents found a new spiritual home in nearby Magdeburg, the imperial free city that in 1548 had most loudly proclaimed its defiance of the emperor and the Interim. For three long years, until forced to capitulate to the besieging armies of Maurice and his allies, Magdeburg held out, a beacon of resistance to the emperor and his subjugation of Lutheranism.

10

The energizing spirit of this resistance was a man of a younger generation, Matthias Flacius Illyricus. Flacius was also part of the Wittenberg circle, appointed professor of Hebrew in the university in 1544 at the age of twenty-four. But he was not one of the initial band of brothers, and can only have known Luther in his late, declining years. Having removed to Braunschweig at the suspension of the university in 1546, Flacius had little appetite for an institution living under the Interim, and in 1549 he transferred to Magdeburg. Here he swiftly emerged as one of the most skillful polemicists of defiance. His response to the Interim, and his former Wittenberg colleagues, was brutally simple: the Interim was a deception, little more than a camouflage for the reintroduction of Catholicism. The appeal for unity and order, for obedience to the state power, could not justify a denial of the true faith. As it was succinctly

stated in an open letter from the Hamburg ministers to the Wittenberg professors, twice reprinted in Magdeburg, it was most unsafe “to place one’s trust in princely courts to the exclusion of God’s Word.”

11

Behind all of this, and the indignant wounded replies of the Wittenberg faculty, floated the unstated question: What would Luther have said? What would he have done in this situation? There was little doubt that those gathered at Magdeburg and their allies in the north German cities believed that they were the real keepers of the flame.

It was not just in its theologians that Magdeburg sought to inherit the mantle of Wittenberg: the same could be said of its printing industry. The two principal printers of the pamphlet polemic had both cut their teeth in Luther’s school for bookmen. Michael Lotter, when he moved to Magdeburg, was already an accomplished printer, having first arrived in Wittenberg to assist his brother, the soon disgraced Melchior, in the early 1520s. Michael lingered for a few years after his brother’s departure, before transferring definitively to Magdeburg in 1529, where he built a lucrative line in reprints of Wittenberg editions of Luther’s works.

12

In 1539 he was joined by Christian Rödinger, whose Wittenberg apprenticeship had been far more brief. In Magdeburg he, too, built a substantial business through the publication of Luther and his supporters. The presence of these two canny and established operators meant that it was relatively easy to gear up production when Magdeburg enjoyed its brief moment at the eye of the storm: in the five years between 1548 and 1552 the Magdeburg presses turned out 460 works.

13

This output was wholly dominated by the pungent polemical pamphlets of the resistance. As a media campaign they exhibit all the features that we recognize from Wittenberg in the 1520s: clarity of purpose and intellectual coherence, reinforced by a clear if simple design identity. Magdeburg offers a further striking example of the capacities of the printing industry to respond to the rapid fluctuations of demand that followed the great events of the Reformation.

M

AGDEBURG

R

ESISTANCE

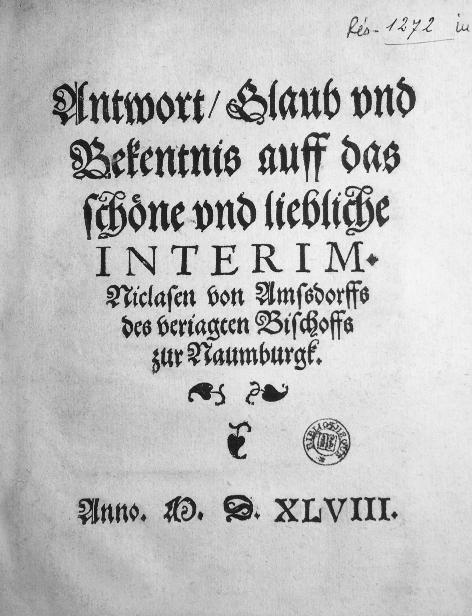

As Wittenberg was compromised by its stance during the Interim controversy, Magdeburg and Jena emerged as new centers of Lutheran resistance. This attack on the Interim was printed by Michael Lotter, a printer who had started his career in Wittenberg in the workshop of his brother Melchior.

There was little doubt that in this respect the siege of Magdeburg was a true defining moment: the time when in defense of the faith Lutherans turned from theoretical considerations of the right of resistance to open defiance of the emperor’s power. Magdeburg’s sacrifice, and ultimate vindication in the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, was a sign that the critical mass of Lutheran powers would choose the clarity of orthodoxy rather than the subtle syncretism of Melanchthon. The strength of this feeling was graphically demonstrated when John Calvin, the young reformer of Geneva, attempted rather unwisely to fish in these troubled waters.

14

The ostensible cause was the rough handling of

a group of evangelical exiles expelled from England on the death of Edward VI, and denied entry to a succession of north German Lutheran towns in a bitter winter while in search of a new home. Calvin was scandalized by this lack of evangelical fellowship. When he took aim against the spokesman of the Hamburg church, Joachim Westphal, he expected Melanchthon’s support. But Melanchthon, bruised and dejected from the violence with which he had been assailed within the Lutheran family, kept silent, and Calvin was further surprised by the vigor with which other Lutherans rallied to Westphal’s side. The Genevan beat a swift retreat: he had badly misjudged the temper of German religion after this traumatic decade, and indeed, the extent to which Melanchthon had been humbled by his call for temperance and accommodation.