Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (22 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

In many respects this was the most unfortunate of the dramatic set-piece events of the Reformation. Several of Luther’s colleagues had misgivings about the burning of Canon Law; his defense, after all, had to this point relied on due process, and this seemed out of keeping with Luther’s insistence on appeals to his professorial status and the authority of the general council. The original intention had been to include in the pyrotechnics a copy of Duns Scotus, as representative of the despised

Scholastics, but none of the Wittenberg professors had been willing to sacrifice their copy of such a valuable book.

22

It is surprising indeed to find Philip Melanchthon associated with such a gaudy occasion, but the loyal Philip had long recognized that Luther was a force of nature not to be contained. Needless to say the students present reacted with exuberant enthusiasm, adding their own offerings to the blazing pyre, and the professors were obliged to retreat with what could be mustered of their dignity.

This tawdry act of theater ultimately achieved very little, beyond providing an opportunity to relieve some of the pent-up tension of the long period of waiting for papal judgment. On January 3, 1521, the grace period for Luther’s submission having expired, a new bull declared Luther’s final excommunication. In practice, though, the crucial event had occurred two months previously when Frederick the Wise had met the papal legate, Jerome Aleander, in Cologne. Frederick made unambiguously clear that he would not enforce the bull against Luther. The conflict, if it were to be resolved at all, would only be resolved politically.

So for Luther life went on much as before. Although formally released from his monastic vows, Luther had no immediate plans to abandon his black habit or to leave the monastery. He did, however, welcome release from the obligation to perform the monastic devotions, with which he had fallen hopelessly in arrears. The greater impact was on the wider Wittenberg community. While Luther had had many months and years to prepare for a life outside the Roman obedience, his colleagues suddenly had to face a future in a university now identified as a rogue institution radically separated from the wider Germany and international intellectual community. Perhaps indeed this was the real purpose of the book burning of December 10, a public act of separation on behalf of the community. Not all approved: in 1521 Wittenberg would witness a sharp fall in student enrollments, as parents considered the implications of committing their children to an institution now effectively in schism. But those who remained lost none of their enthusiasm for Luther. In the days before Lent the students integrated into their

traditional revels pointed mockery of the pope and his cardinals. And it was in these same months that Lucas Cranach embarked on his definitive pictorial representation of the separation of the churches, the

Passion of Christ and Antichrist

.

23

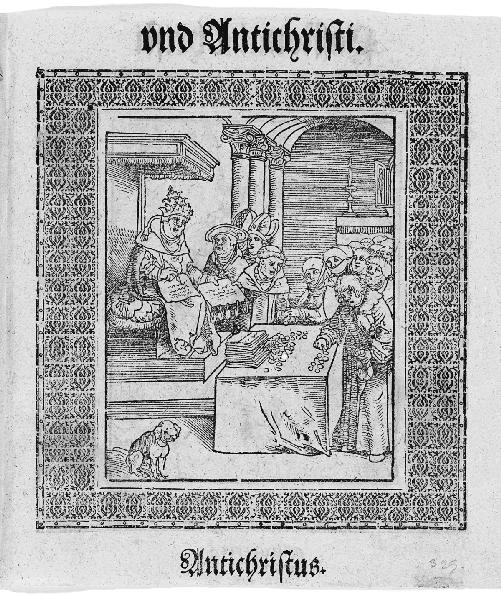

Thirteen paired sets of woodcuts depicted on one side Christ and his disciples, and on the other, the pope in his pomp. While Christ preaches and performs acts of mercy, the pope feasts; while Christ drives the money changers from the Temple, the pope gathers money into his indulgence chest. As so often, the Wittenberg movement met Luther at his most radical and scandalous and embraced the consequences.

While these events were played out in Wittenberg, the Imperial Diet was locked into an angry trial of strength over Luther’s fate. The young Emperor Charles V was insistent that he would not allow Luther to appear at the Diet; the Estates, in turn, refused to allow Luther to be condemned unheard. Only after weeks of wrangling was a compromise of sorts achieved. Luther was to be summoned to answer for his writings, but without any disputation: Worms was not to be a platform for the heretic to make his case. On March 6, Charles put his reluctant signature to the letter of summons, and the imperial herald set off to bring Luther from Wittenberg. For the duration of the hearing he would be under the emperor’s protection.

The herald arrived in Wittenberg on March 26; within a week Luther had departed, accompanied by three colleagues and the good wishes of the city council, which provided a generous sum toward travel expenses. It rapidly became clear that this financial support would be largely superfluous, as Luther was warmly welcomed at every staging post: at Leipzig, Naumburg, and then at Erfurt, where he was conducted by a large civic delegation to his former home at the Augustinian house. The following day, a Sunday, Luther preached, as he would again in Gotha and Eisenach later in the week. Everywhere Luther appeared he was surrounded by curious and sympathetic crowds. Forewarned by the angry reactions to attempts to exhibit the papal bull, those who did not support Luther kept a low profile. Yet this rapid trek across Germany,

constantly in the public eye, took its toll on Luther. By the time his party had reached Frankfurt he had fallen sick. There was little time for recuperation, since two days later he was in Worms.

P

ASSION OF

C

HRIST AND

A

NTICHRIST

Cranach’s wonderfully realized image of the pope personally supervising the indulgence trade was as evocative and hard-hitting as any modern cartoon.

Three years before, he had made his way to Heidelberg and then to Augsburg largely unknown. Now in Worms the city trumpets were sounded to herald the arrival of a distinguished guest; one hundred horsemen rode out to escort him through the gates; as he descended his carriage a monk reached down to touch his hem. This was all witnessed by informants of the incredulous papal legate, who had counseled against the emperor receiving Luther.

24

Aleander’s own arrival had been very different: despite liberal supplies of money he had been unable to secure anything but a small, unheated room, and he was forced to endure gibes and threatening gestures when he ventured forth on the streets. He noted, too, that all the booksellers’ stalls were crammed with Luther’s writings and exhibited his picture for sale. Aleander was used to conducting his business behind closed doors; now he had seen at firsthand just how forcefully Luther’s cause had engaged the German nation, and he was badly rattled. “Now the whole of Germany is in full revolt,” he reported to Rome; “nine tenths raise the war cry ‘Luther,’ while the watchword of the other tenth who are indifferent to Luther is ‘Death to the Roman Curia.’” And Luther had clearly struck a chord with his appeal for a general council: according to Aleander, “All of them have written on their banners a demand for a council to be held in Germany, even those who are favorable to us, or rather to themselves.”

25

After his triumphant entrance Luther’s actual appearance before the Diet may have seemed somewhat anticlimactic. In the late afternoon of the following day Luther was summoned to the crowded room where the Imperial Estates were gathered. Here he was confronted by a pile of his books. The imperial spokesman, Johann von der Ecken, now asked whether Luther would acknowledge that he had written them, and whether he would renounce the heresies they contained.

26

At the request of Luther’s lawyer the titles of the books were read and Luther acknowledged his authorship; but, to general perplexity, he asked for more

time to consider his reply to the second question. This was grudgingly granted, so the next day Luther returned, and managed, despite interruption, to repeat his denunciation of the papacy while differentiating other of his writings that dealt with practical Christian morality. After a brief adjournment von der Ecken pressed for a direct answer: Would Luther recant? This last hope of reconciliation and compromise Luther now definitively repudiated:

Unless I am convinced by testimonies of the Holy Scripture or evident reason (for I believe neither in the pope nor councils alone, since it has been established that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures adduced by me, and my conscience has been taken captive by the Word of God, and I am neither able nor willing to recant, since it is neither safe nor right to act against conscience. God help me. Amen.

27

The young emperor was scandalized, but many of those present believed that Luther had handled himself well; they insisted that a small commission should be established to examine him further. To the emperor’s frustration and humiliation, three days were set aside for these discussions, but it was Luther who brought them to an end. On April 26, he left the city, escorted again by the imperial herald. In his absence the wrangling continued, and it was only on May 26 that the emperor finally got his way and Luther was placed under the imperial ban.

Long before this Luther had disappeared. The evidence of both popular enthusiasm and support for Luther among his fellow princes may have emboldened the elector to pursue the dangerous course on which he had now determined. Rather than give Luther up, he would be spirited away to protective custody. Thus without open defiance of the emperor, Luther would be protected from the consequences of the imperial interdict. So it was that in the Franconian Forest beyond Eisenach, Luther and his companions were intercepted by a band of mounted knights. Luther was taken, dressed as a knight, to an isolated castle, the Wartburg.

SECLUSION

Luther would remain at the Wartburg for ten months. At first his location, even the fact that he was alive, was a closely guarded secret: in Wittenberg only Melanchthon, Spalatin, and Nicolas von Amsdorf, another stalwart friend, knew of his whereabouts. But the steady stream of messengers, letters, and books must have brought an ever-widening circle into the elector’s confidence.

28

If they did not know precisely where he was, many must have known Luther was alive from the evidence of his continuing literary activity.

The months at the Wartburg were not easy for Luther. He had lived the last four years in a fury of action, surrounded by people, shaping events. Now he was alone, more alone even than his first months in the monastery, and without the monastic offices to shape and guide his devotions. Luther appreciated the irony of this, telling one correspondent, “I have no more news, since I am a hermit, an anchorite, truly a monk, though neither shaved nor cowled.”

29

In his letters to Wittenberg friends—a real lifeline—Luther insists so frequently on his patient obedience to God’s will that the effort this required of him is palpable. He also had to believe that in his absence his movement, his case, and his university were all in safe hands. He hated being out of the swing of things, passing on such snippets of news as came his way and yearning for more. But at least he could still write, and this he did, incessantly. The messengers from Wittenberg brought news, supplies, and sometimes proof sheets for correction; they departed back with new manuscripts for the press.

Initially, at least, he occupied himself with the reverberations from Worms and the papal condemnation. In June Luther penned a refutation of the Louvain theology professor Jacobus Latomus, who had offered a considered justification of the faculty’s condemnation of Luther’s teachings. Luther also took the first opportunity to reply to the adverse

judgment of the Paris Sorbonne.

30

The delivery of Jerome Emser’s latest contribution to their rather fruitless exchanges also merited reply.

31

But Luther’s removal from the hurly-burly of the pamphlet wars in due course had the rather positive consequence that the polemical aspect of Luther’s writing steadily receded. There was also the practical point that all of the correspondence to and from the Wartburg passed through Georg Spalatin, who could, therefore, exercise some prudent control over the texts that should be passed to the printer. A sharp denunciation of Albrecht of Mainz, who had announced a new indulgence for his relic collection in Halle, fell under this embargo.

32