Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (26 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

B

RAND

L

UTHER

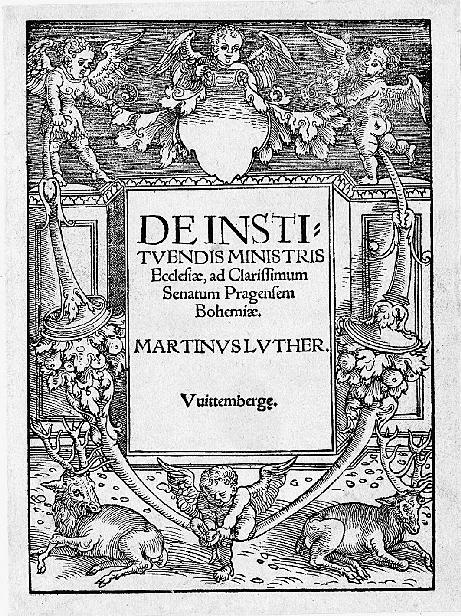

Here all the elements of marketing Luther are included: the highlighting of name and place, and Cranach’s distinctive title frame.

What Cranach had achieved with these new title-page designs was not easy: it required the combination of Cranach’s skills as a pragmatic, practical spirit and his enormous artistic imagination. To this point in the history of art, narrative images were most effectively achieved within a

landscape format, where the story could flow naturally across the canvas. A book inevitably required an upright, portrait format. Furthermore, the design had to be fitted around a central block of empty space, where the title text could be inserted. This was a unique problem in the history of visual art. Cranach’s solutions were ingenious, with broad blocks at the top and bottom, allowing room for vertical figures up the sides and decorative putti around the corners. This use of corners was, of course, impossible when a framing border was created from four separate blocks. The extensive use of landscape foliage and animals from the hunt drew on Cranach’s experience painting hunting scenes for Frederick’s court. Other title-page designs use classical motifs such as the judgment of Paris (another favorite subject for his workshop) or Pyramus and Thisbe. The title-page borders by and large make no allusion to the pamphlet’s contents, and were indeed frequently reused for different titles. The exceptions were those occasions when Cranach designed biblical scenes as title-page decoration: the blinding of Saul (for an edition of the Epistles and Gospels), Samson and the lion, David and Goliath (for an edition of the Psalms).

31

Cranach also took the opportunity to incorporate into his title pages one of his true masterpieces, The Law and the Gospel.

32

This was one of the most innovative pieces of religious iconography generated by the Reformation, an original composition of Cranach’s contrasting the old Law (of Moses and the Old Testament) with the new covenant of Christ. The two are divided by a tree, blasted on the side of the old Law, green and flourishing on the side of the new. Complex and intricate in its original manifestation as a panel, to reconfigure this as a title page, with blank central space for the title, was one of the great design achievements of the age.

33

The accumulation of this portfolio of ornate title-page woodcuts occupied the Cranach workshop for the best part of two decades, and in the process they totally changed the appearance of Reformation

Flugschriften

. Wittenberg’s printers embraced them without hesitation; not just Melchior Lotter, who worked on Cranach’s premises (but with whom the painter soon fell out), but other newcomers to the Wittenberg

printing industry: Joseph Klug, Georg Rhau, Nickel Schirlentz, and Hans Lufft. Even Rhau-Grunenberg embraced the new style. At last Wittenberg books could face the world in a livery that expressed the dynamism, sophistication, and optimism of the new movement.

Printers elsewhere soon sat up and took note. It was in the nature of the industry that such a radical innovation could not easily be confined to Wittenberg. Cranach’s design breakthrough was soon being carefully examined by other industry professionals wherever Wittenberg books were sold. This was the way the book world worked—in fact, the way it had worked since the first proof sheets of Gutenberg’s Bible had been exhibited at the Frankfurt Fair in 1454. Many printers attended the regular book fairs in Frankfurt and Leipzig not because they needed to do so to sell their books, but so they could cast a professional eye over the work of their competitors and see what looked new and interesting. As a result of this scrutiny, Cranach’s most successful designs were soon being shamelessly copied in both Augsburg and Nuremberg.

34

Cranach was no doubt relatively phlegmatic about this; he knew how the game was played. This was an age with no real concept of intellectual property, and the protection of a monopoly was only as good as the jurisdiction in which it was issued. The overall impact of this rampant copying, however, was undoubtedly to improve further the design coherence of the Reformation

Flugschriften,

as Cranach’s innovative designs were copied into new markets.

The distinctive look provided by Cranach’s title-page designs was the final component of a puzzle that had been taxing Germany’s printers since the early days of the Reformation: how to make the most of their most marketable property—the new phenomenon that was Martin Luther. This resolution was not reached without a certain number of false starts. One was the use of Luther’s image in book art. The first attempt to incorporate an image of Luther on a title page appears on a pamphlet account of the Leipzig Disputation; it, therefore, predates Cranach’s iconic portraits. Perhaps for this reason it cannot be counted a success. The representation of Luther in a doctor’s cap is no more than a cipher

without real recognizable features. The overall effect is not helped by the fact that the lettering in the surrounding inscription is reversed, and can only be read with a mirror. This was clearly rushed out to cash in on Luther’s new notoriety. Between 1520 and 1522, rather more successfully, a Strasbourg publisher, Johann Schott, used locally cut copies of Cranach’s representation of Luther in his monk’s garb, one on the title page of a pamphlet and the other on the inside cover.

35

But this, too, failed to catch on. A movement that articulated the primacy of the Word was never entirely comfortable with the promotion of any sort of personality cult around Luther. One of the Strasbourg pamphlets captured this dilemma perfectly by portraying Luther with the nimbus of sainthood, a particularly inappropriate image given Luther’s criticism of the cult of saints.

36

No book published in Wittenberg during these years ever included a portrait of Luther on the title page, and this early attempt to popularize the reformer’s image alongside texts of his writings soon spluttered and died.

Luther’s name was a different matter. In the design of the Reformation title page we also see printers gradually waking up to the potency of Luther’s personal reputation as a writer and teacher. Very early works often buried Luther’s name in the midst of a dense block of text; not infrequently his name was split over two lines of text (Lu- / theri) if that was what was dictated by the blocking. This simply obscured the book’s most obvious selling point, as printers quickly recognized. Soon they had learned to move the name, “Mart. Luthers,” “Martin Luther,” “Doct. Martin Luther,” into a line of its own, often separated from the main body of the title. The name is often in a bold type of larger size, in a manner calculated to spring off the page, catching the eye of purchasers surveying a mass of titles piled up on the bookseller’s stall.

The last element of brand identity was Wittenberg itself. In most parts of Europe it was now common practice for the printer’s address to be printed in a neat, small type at the bottom of the title page. Not so in Wittenberg. Here the printer’s name was mostly relegated to the end (the colophon) or omitted altogether. Instead the city was given pride of

place, often on a single line at the bottom, separated by an inch or more of white space from any other text.

That Wittenberg was now an essential part of the brand—the seal of quality and authenticity—is demonstrated by the number of times this strategy is employed even on pamphlets printed elsewhere. A number of Augsburg printers, for instance, took to printing “Wittenberg” starkly on the lower part of their title pages. Perhaps, being charitable, one could suggest that the printers were simply advertising the fact that the text itself was from Wittenberg, or that it was the work of Martin Luther of Wittenberg. Either way, whether calculated to deceive or intended to inform, it makes the point that within a few years, thanks largely to Lucas Cranach, Wittenberg had thrown off the clumsy provincialism that had marred Luther’s first publications. Now Luther’s city could offer finished products worthy of their contents: pamphlets that in their design and appearance confidently proclaimed the unbreakable connection between the movement’s progenitor, Martin Luther, and the place with which his church was now indelibly associated, Wittenberg. That would be the enduring achievement of Brand

Luther.

7.

L

UTHER

’

S

F

RIENDS

T MANY TIMES SINCE

T MANY TIMES SINCE

the first years of the Reformation Luther had felt the loneliness of command: waiting on Cajetan’s decision at Augsburg, facing the assembled Estates of the Empire at Worms, incarcerated at the Wartburg. On such occasions he took comfort in a sense that none of this had come about through his own volition; he was, as he frequently reflected, simply the instrument of God’s purpose. This sense of special calling was undoubtedly reinforced by the long months of brooding isolation at the Wartburg, and the swift reassumption of leadership on his return. The self-confident acceptance of the responsibilities of leadership is reflected in a significant change in Luther’s bearing. We see this in the style of greeting used in Luther’s correspondence, which he now increasingly begins with the Pauline “grace and peace.” This assumption of apostolic mission was already a familiar trope among Luther’s followers. To Christoph Scheurl of Nuremberg Luther was a preacher “through who alone Paul speaks”; to Ulrich von Hutten “a man of God and apostle of Christ.”

1

Other early writers evoked the Old Testament prophet Elijah and heralded Luther as a new Daniel or the good shepherd who Ezekiel had prophesied would tend the flock of Christ.

2

All of this contributed to the idea of a man alone, singled out by

God to perform great things: the simple monk whose bold challenge had shaken the kingdom of Antichrist to its core. This intense focus on the person of Martin Luther was encouraged in the public mind by the wide circulation of woodcut images of the reformer, always in the first years presented as a solitary figure, in monk’s cowl, with the gaze of the visionary and the humble bearing of a true servant of Christ.

3

In the years before and after the dramatic confrontation with the emperor at Worms in 1521, public interest in Luther as the symbol of national resistance to an alien authority far outstripped any public understanding of his theology. This, as the perplexed and angry papal nuncio Aleander had recognized, was the key to his potency—and danger.

Of course, as Luther was well aware, this perception vastly oversimplified the motive power of his movement. Indeed, had Luther been such a solitary figure, the man alone, the voice crying in the wilderness, his Reformation would quickly have died. Certainly the movement could not have been sustained once the drama of Worms faded from memory. Luther would not have survived to face his critics at the Diet without the steady support of influential friends who had stuck with him through all the twists and turns of the previous four years. These crucial early supporters included, as we have seen, ecclesiastical superiors such as Staupitz, university colleagues, Georg Spalatin at the Saxon court, and the Elector Frederick, his enigmatic and to Luther largely silent patron. Pondering the increasingly worrying developments in Wittenberg during his enforced absence in 1521, Luther looked to Melanchthon to take on the burdens of leadership, and to his friends on the city council, Cranach and Döring, to hold the line for the necessary measures to restore order.

4

Luther, as politically literate as he was theologically inspired, was well aware of the need for friends.