Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (21 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

By the beginning of 1520 Luther was clear enough how things would end in Rome; his definite condemnation was only a matter of time. His appeal to a general council was a deft legal maneuver, but no more than that; successive popes had definitively pronounced against any such appeals, and Luther’s attempt to invoke a general council would form one more article in the condemnation of his heresies in

Exsurge Domine

. So in the summer of 1520 Luther decided to preempt papal condemnation by inviting the new Emperor Charles V to take in hand the long-delayed reform of church abuses within the German Empire.

In making this appeal, Luther could associate himself with a long tradition of church criticism that had recently taken on a profoundly nationalistic tone. A large part of the resentment of indulgences had been the perception (not always rooted in reality) that large sums of money were in this way being drained from Germany to enrich Rome. Complaints of this sort were regularly aired among the grievances (

gravamina

) submitted by the German Estates at meetings of the Imperial Diet.

In his address

To

the Christian Nobility of the German Nation

Luther set out to show that the necessary reform of the church could only be addressed by the German people acting independently.

16

The Roman Church had become so irredeemably corrupt that it lay beyond reform. In making the case, as ever, Luther deepened and broadened the theological

precepts on which he made this appeal. To empower the German laity, Luther had first to demolish the ring of fortifications behind which lay the claim to papal primacy. These included the pope’s claim to be the final and infallible interpreter of Scripture, and the assertion that only a pope could call a general council. Most critical was the first line of defense: the pope’s claim to superiority over any secular power. Luther’s demolition of this claim was based on a challenge to the radical separation between the lay and clerical estates that had been a fundamental organizational principle of medieval society. Luther, on the contrary, denied that the distinction between priest and layman had any scriptural validity. Rather, all baptized Christians were, by virtue of their baptism, members of a priesthood of all believers.

The manifesto went on to say a great deal more. There was a long and eloquent denunciation of the total corruption of the papacy, which had turned Rome into a giant bazaar:

At Rome there is such a state of things that baffles description. There is buying, selling, exchanging, cheating, roaring, lying, deceiving, robbing, stealing, luxury, debauchery, villainy, and every sort of contempt of God that Antichrist himself could not possibly rule more abominably. Venice, Antwerp, Cairo are nothing compared to this fair and market at Rome, except that things are done there with some reason and justice, while here they are done as the Devil himself wills.

Was Luther here recalling the bewildered young monk, amazed at the cynicism and worldliness he encountered on his trip to Rome in 1510? As he warmed to his theme, he enrolled the sympathies of all who had experience of the multitude of fees that smoothed the way of the church and civil government.

What has been stolen, robbed, is here legalized. Here vows are annulled. Here the monk may buy freedom to quit his order. Here the

clergy can purchase the marriage state, the children of harlots obtain legitimacy, dishonor and shame be made respectable, evil repute and crime be knighted and ennobled. Here marriage is allowed that is within the forbidden degree, or is otherwise defective. Oh what oppressing and plunder rule here! So that it seems as if the whole canon law were only established in order to snare as much money as possible, from which everyone who would be a Christian must deliver himself.

17

The tract closed with a potpourri of radical recommendations: that all the mendicant orders should be combined into one; that clerical celibacy should be abolished; that masses for the dead should be discontinued; that usury should be prohibited. But it was the “priesthood of all believers” that would be the radical time bomb ticking away at the heart of this work, a loose phrase that Luther would have plentiful opportunity to regret.

Published in August 1520,

To the Christian Nobility

was an instant sensation. Lotter, no doubt working on more than one press, contrived an edition of four thousand copies, quite unprecedented for this sort of work. Even so it sold out within a fortnight. Luther was able to make some modest additions for a second edition, which appeared before the end of the month. A remarkable ten further editions spread the message through Germany through the now customary chain, Leipzig, Augsburg, Basel, and Strasbourg.

18

Luther was aware that not all approved the sharply polemical tone, but it hit its mark with the first intended audience, Germany’s princes and civic leaders. Luther had deftly associated himself with their cause, and with their long-standing grievances about the financial power of the church. They could warm to his neat encapsulation of these sentiments, without necessarily seizing the radicalism of the underlying theological precepts. At a time when Luther’s fate was being actively debated among those preparing for the next crucial meeting of the Imperial Diet, this was a vital constituency.

Even before

To the Christian Nobility

was published, Luther had

turned his attention to the second of these three great works,

The Babylonian Captivity of the Church

.

19

The title alone reflects his sense of utter alienation from the institutional church. The Christian people were, like the people of Israel, held in tyranny and bondage by the Roman hierarchy. This was a complex work, written in Latin for a scholarly audience. Luther began rather sensationally by repudiating some of his early writings, which he now found overly timid. For Luther’s restless search for fundamental truths had led him to a root-and-branch reassessment of the Roman sacramental system. Of the seven sacraments that underpinned the Christian life, Luther was now prepared to recognize only three: the Eucharist, baptism, and (with reservations) penance. It was in his treatment of the Mass that Luther most stunned his readers. The Church had surely erred in denying the laity the cup: in this, he now calmly proposed, the Bohemian Hus had been correct. But the core of the issue lay in his denial of the central sacrificial act that lay at the heart of the Mass, transubstantiation.

In asking his clerical readers to repudiate their whole sacramental system, Luther offered his most shocking view of his new theological program. The Mass lay at the heart of the clerical office. By paring back the sacraments from seven to three, Luther had demolished the church’s role as a sacramental institution, nourishing the Christian from cradle (baptism) to death (extreme unction). No wonder many of its readers regarded this as the most scandalous of all Luther’s writings.

The Freedom of a Christian Man

took a different tone altogether. After the excoriating, unsparing exposition of reform in church and society, this was Luther describing his personal revelation of salvation that awaited all true Christians. The freedom of the Christian man was the liberation that comes to a Christian justified by faith. With this, the last of Luther’s major expository works of 1520, Luther brought to its conclusion the reflections on the Christian life so powerfully begun with

The Treatise on Good Works

some six months before. Luther freely affirms that the true Christian will live a life of service to his fellow believers, moved by God’s love and love for his fellow men. But the good works that flow

from Christian charity will never win salvation, for that salvation is already assured. Accepted in faith, the message of Christ brings assurance to all Christians without further demonstration of piety. Thus is the whole penitential system of the church overthrown, though, without the theatricals of Luther’s other major writings in this period, the radical impact of this new theology may well have escaped the first generation of readers.

The Freedom of a Christian Man

has the most complicated publication history of the three great treatises of this year. The German edition, probably completed first, was dedicated to the mayor of the city of Zwickau, Hieronymus Mühlpfordt. The Latin edition was prefaced instead by an open letter to the pope.

20

This represents a last, rather resigned response on Luther’s part to the incessant and increasingly frantic diplomatic activity of Karl von Miltitz. In August von Miltitz had informed the elector that he would pursue another attempt at mediation. Luther was skeptical, especially when he learned that

Exsurge Domine

had already been published. But he agreed to meet von Miltitz and was persuaded that no harm might come of a letter assuring the pope that their quarrel was not a personal one. This Luther duly appended to the Latin text, praising Leo for his personal piety and denouncing those that surrounded him. Leo, he assured the pope with fraternal concern, was merely the sheep among wolves. Quite what anyone would have made of this in Rome is hard to imagine, particularly if it had arrived with copies of Luther’s

To the Christian Nobility,

with its vivid tour of the domain of Antichrist, or the

Babylonian Captivity

. But if it helped present Luther to the more important audience gathering for the Diet as a man eager for peace, then it would have served some purpose.

Both Latin and German editions of

The Freedom of a Christian Man

were published on November 20, the climax of an extraordinarily fertile period of literary creativity. In the space of one year Luther had written twenty-eight different works, which ranged across the gamut of pastoral instruction, pungent works of polemic, appeals for reform, and fundamental works of theology. Only the continued publication of his lectures

and commentaries was squeezed out by the pressing obligations of this crowded year. Once again Germany’s printers were the beneficiaries, turning out over three hundred editions of Luther’s works, along with a considerable number written by others drawn into the controversies on either side. But the time had surely come for resolution. As

The Freedom of a Christian Man

left the print shop, Luther had three weeks left to make his reply to

Exsurge Domine

. He had conceived a special ceremony to mark the occasion.

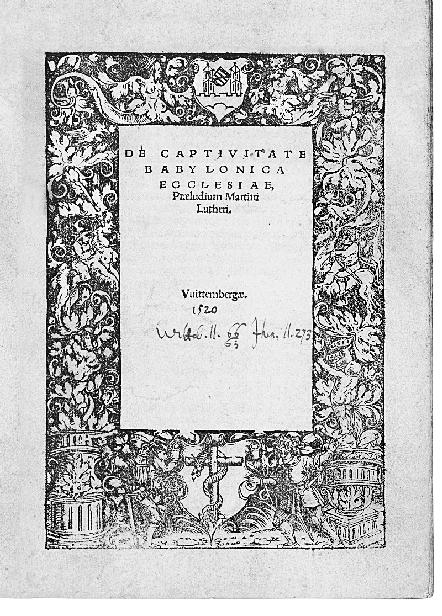

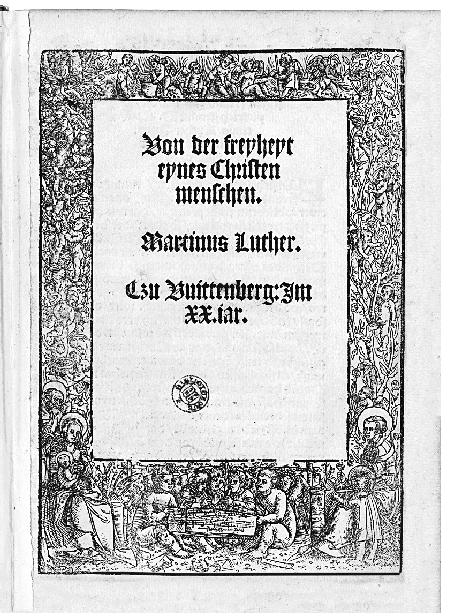

T

WO

M

AJOR

M

ANIFESTOS OF 1520

De captivitate babylonica ecclesiae (The Babylonian Captivity of the Church)/Von der freyheyt eynes Christen menschen (The Freedom of a Christian Man).

Already the combination of Melchior Lotter’s craftsmanship and Cranach’s new revolutionary title-page designs was transforming the look of Wittenberg books.

WORMS

On December 10, 1520, Philip Melanchthon posted on the door of the university church the invitation to colleagues and students to witness “a pious and religious spectacle, for perhaps now is the time when Antichrist must be revealed.” This was to take place not in the customary place of academic debates, but outside the Holy Cross Chapel, at the east end of the town, near the stockyards, where cattle were butchered and the clothes of those who had died of plague were burned. Here a pyre had been erected, and once the solemn gathering had assembled and the fire had been lit, Luther cast into it a range of representational texts of the old church: papal decretals, a copy of the Canon Law, and some of the polemical works of Eck and Jerome Emser. Luther kept a list, which he defiantly shared with Spalatin in a letter later that day.

21

At the last moment Luther plucked from his cloak a copy of the papal bull, and that, too, was hurled into the flames.