Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (25 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

With the factory on the Schloβstrasse Cranach had embarked on the first of a series of acquisitions that would in due course make him the owner of nine separate properties around Wittenberg. One was a second substantial house on the market square at Markt 4; it was here that Cranach lived between 1513 and 1517 while the major building works were under way fifty yards away. (The house at Markt 4 is now the location of the Cranachhaus Museum.) This beautiful building, which he also remodeled in the finest Renaissance style, had been purchased from Martin Pollich von Mellerstadt, first rector of Wittenberg University and Frederick’s personal physician. Von Mellerstadt had negotiated a lucrative privilege to operate an apothecary business, and Cranach made sure that he inherited this also. This may seem an unusual diversification, but for Cranach it made perfect sense. There were good profits to be made from the supply of herbs and spices to the students, professors, and local inhabitants, and Cranach, in addition, also had a monopoly on the sale of sweet wines in the city. An apothecary shop was an important place of information gathering. Citizens would come by seeking remedies for trifling or more serious afflictions (or send their servants to fetch them). While they were waiting for these potions to be mixed, they would stop and gossip. Customers would also consult the apothecary about the most likely remedies for pain or debilitating conditions. So the proprietor of such a business held the community’s most intimate secrets, and in this case his boss was Wittenberg’s most shrewd and substantial businessman.

20

In a world where almost all major business transactions functioned on credit, the apothecary shop provided priceless nuggets of information about who might be in failing health, who had a secret affliction not yet revealed to creditors, and whose business might soon be available for purchase. Quite apart from its generous profits (always good for cash flow), the capacity this business gave its proprietor to measure the pulse of the city made this one of Cranach’s shrewdest investments.

By 1517 Cranach was one of Wittenberg’s most substantial citizens. A decade later his tax assessment placed him among Wittenberg’s three wealthiest inhabitants, and certainly he was its most active and energetic business entrepreneur. In 1519, like Luther’s father in Mansfeld, Cranach took his place on the city council, the beginning of a thirty-year involvement in municipal politics, during which he would serve three times as the city’s

Bürgermeister

. Inventive, versatile, and where occasion demanded quite ruthless, Cranach was a force to be reckoned with. When in the early 1520s he turned his attention to Wittenberg’s expanding printing industry, the impact was immediate and transformative.

THE GODFATHER

It is not known when Cranach and Luther first became acquainted. In their first years in Wittenberg the two men moved in very different circles. Cranach was by some distance the more distinguished of the two, constantly in the elector’s presence and from 1512 permanently established in the center of the town and its most eye-catching dwelling. But sometime around 1518 the two men became friends. Cranach would have attended Luther’s sermons in the town church. From his court connections he would have known of the reverberations that followed the austere professor’s provocative theses. He was impressed—and fascinated; at an early stage Cranach would become a committed and important supporter of Luther’s new movement.

This support came with limits. For all his loyal service to the Reformation, Cranach never ceased working for Catholic clients, including Albrecht of Mainz.

21

If Luther objected, then on this occasion he sensibly kept his counsel. In other respects the two friends were well matched. They were roughly of the same generation (Cranach was born in 1472, eleven years before Luther) and both had now reached their full maturity. Both were powerful, driven men, who took easily to positions of responsibility: both knew how to inspire loyalty and to command

obedience. Both, too, came to married life relatively late, Cranach in 1512, at the age of thirty-nine, and both would become devoted parents: between 1513 and 1520 Barbara Cranach became the mother of five children, two of whom would follow into their father’s business. Luther was honored to be chosen as godfather to one of the children; in due course Cranach would return the compliment, after Luther’s own far more controversial marriage in 1525. Cranach was, in fact, one of the very few present at this discreet ceremony. This was a relationship of mutual respect, mutual affection, and mutual benefit. Cranach gave the Reformation some of its most memorable images; Luther in return would take a strong line against the radical rejection of pictorial art promoted by some of his Wittenberg colleagues. Cranach, civic leader and artistic entrepreneur, would be one of the rocks on which the Wittenberg Reformation would be built.

Cranach’s first signal service to the Reformation came in fashioning the three iconic portraits of Luther that made his physical features known beyond the relatively narrow group of those who had encountered him in person. The initiative for the first portrait—an engraving—seems to have come, curiously enough, from Albrecht Dürer. A passionate admirer of Luther from his first reading of Luther’s works, Dürer regretted the lack of a true likeness of the reformer. He wrote suggesting that such a likeness be created, enclosing copies of his magnificent woodcut portrait of Albrecht of Brandenburg as a model.

22

Cranach studied the portrait of Albrecht carefully before embarking on his own rendition of Luther. The result was a triumph, simultaneously a magnificent propaganda piece and a wondrously lifelike rendering of the reformer at this seminal moment of his career (1520).

23

Cranach makes of Luther exactly what the occasion demanded, the simple monk, lean but not gaunt, staring calmly outward, resolute and monumental in the face of adversity: the very picture of the simple man of God, strong against the marshaled forces of the institutional church. It is a fascinating portrait of simplicity in strength and determination.

This image, in fact, was not destined for immediate circulation. In

the months before Luther’s appearance at the Diet of Worms, there were those at the elector’s court who feared that this portrait of heroic resolution might strike the wrong note. Asked to respond, Cranach produced a second image that, while capturing Luther’s inner essence in exactly the same way, gives the appropriate hint of humility.

24

Luther, now shown within a wall niche, places a hand across his heart in a traditional sign of friendship and sincerity; in his other hand is an open book. Once again he wears the monk’s habit.

The third early portrait captured the historical moment when, holed up in the Wartburg, Luther made a brief trip back to Wittenberg to prevent his movement from taking a disastrous turn in his absence. This whole incident reveals much about the intimacy between painter and reformer that had been established by this date. After his condemnation at Worms, the danger to Luther was very real; the success of his removal to protective custody depended on the secret of his whereabouts not being revealed. So it is a measure of the trust that existed between the two men that on a rest stop on the perilous ride to the Wartburg Luther sent an urgent message to Cranach telling him he was in safe hands: “I shall submit to being ‘imprisoned’ and hidden away, though as yet I do not know where.”

25

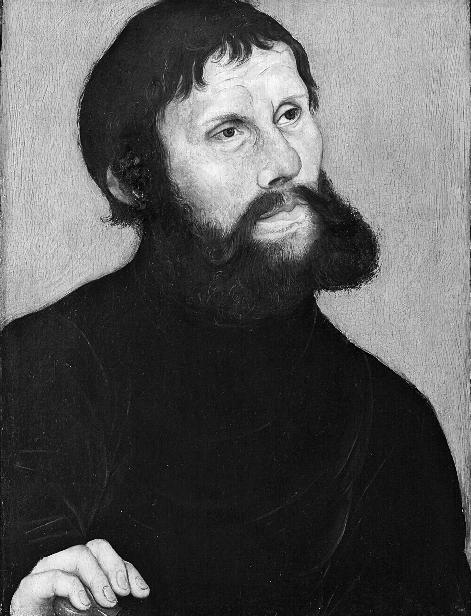

It was Cranach who wrote to alert Luther of the likely consequences if Karlstadt was allowed to introduce radical change in Luther’s absence, and Cranach whom Luther consulted on his secret trip back to Wittenberg on how to prevent the incendiary acts of iconoclasm that Karlstadt seemed to intend. During these urgent and secret consultations, the painter snatched a moment to sketch Luther bearded in his disguise as a German knight, the portrait of Junker Jörg that has become an important milestone in creating the Luther legend. It was also one of Cranach’s first renderings of Luther on a panel painting, the first of a series in which Cranach captured the staging posts of Luther’s life and career.

26

There is the harrowed, hunted figure of 1525, Cranach’s most shocking and evocative psychological portrait;

27

the serene pastor of mature years (the most copied of all his images); the grumpy patriarch of the 1540s. More than any other, this, Cranach’s Luther, is how

history has come to see him. It is an extraordinary portrait sequence of a man who, in any other circumstances, could not expect his true likeness to be known to history.

L

UTHER AS

J

UNKER

J

ÖRG

Sketched by Cranach on Luther’s fleeting first return from the Wartburg, this was the artist’s first panel portrait of him. It was widely disseminated as an equally striking woodcut.

The representation of Luther to the wider world is essentially Cranach’s achievement, and virtually any other contemporary representation, and many after his death, in some way reaches back to this personification by Cranach. So it may seem perverse in the circumstances to suggest that in many respects this was not even Cranach’s greatest service to the Reformation movement. Here we have to take into account a far less heralded achievement of his artistic imagination,

combined with his extraordinary gifts as a business entrepreneur. For if we are to identify the greatest contribution of the Cranach workshop to the promotion of the evangelical movement as a whole, it probably lies not in this portrait art, nor even in the iconic designs created by Cranach to encapsulate the new Reformation theology, but in his contribution to the Wittenberg book industry. The distinctive look of the Reformation

Flugschriften

as they emerged from the print shops of the 1520s owed everything to the design brilliance of Lucas Cranach. It was Cranach who would be the authentic creator of Brand Luther.

BRAND LUTHER

Lucas Cranach became directly involved in the Wittenberg printing industry at the end of 1519, when he became a vital component of the transaction that brought Melchior Lotter to Wittenberg. Cranach was already well-known in Leipzig and to Melchior Lotter Senior, to whom he supplied some of the first of his prototype decorative title pages.

28

So part of the deal was that the son would be provided with work space in Cranach’s cavernous factory at Schloβstrasse 1; Cranach and his partner, the goldsmith Christian Döring, were from the beginning investors in the business. Sometimes Lotter would publish in his own name, on other occasions the press would publish under the imprint of Cranach and Döring. Döring was another of Luther’s closest friends among the citizenry and one of Wittenberg’s wealthiest merchants: it was Döring who had loaned the horses and carriage that had carried Luther and his companions to Worms.

29

He also had a large trucking business, so could handle the distribution of the consortium’s books to other places of sale. At around the same time, Cranach also invested in the purchase of a paper mill: this way he would control the whole of the production process, and through Döring, distribution also. It was a typically bold and decisive intervention in an industry that, thanks to Luther, seemed to promise healthy profit.

The publishing arm of the business was something that Cranach pursued only for a very few years. Perhaps the profits were disappointing, but in truth, this was only likely to be a relatively marginal part of his engagement in the book industry. For Cranach possessed one asset that made him quite indispensable to all of Wittenberg’s printers: a monopoly on the production of illustrative and decorative woodcuts.

It was this that allowed Cranach to play a dominant role in the Wittenberg book trade for three decades; it also allowed him to transform the look of Wittenberg books.

30

To this point Wittenberg imprints had mostly been associated with the spare, utilitarian texts of Rhau-Grunenberg. Printers outside Wittenberg had improved the look somewhat, using decorative borders to frame the title. Cranach offered a radically new solution: a title-page frame, made up not of separate panels but a single woodcut. Here the illustrative features were blocked around a blank central panel into which the text of the title could then be inserted. It was a masterpiece of design innovation, with one step solving the complex problem of integrating text and decorative material while allowing space for imaginative artistic expression on the front of the book.

It was a major and decisive breakthrough in the history of the book, never before applied to texts of this type. Until this point, grand woodcut title-page designs would have been confined to the largest, most expensive books. Cranach’s exquisite work now adorned pamphlets that might sell for no more than a few pence. And what frames these are. Cranach brought to this new engagement with book design the accumulated experience of one of Germany’s most capable and imaginative artistic entrepreneurs. The result is a whole series of masterpieces in miniature, bringing to the title pages of Wittenberg’s Reformation

Flugschriften

a balance, poise, and sophistication that they had to this point entirely lacked. Stylistically this was the part of Cranach’s artistic oeuvre that most self-consciously adhered to the principles of Renaissance art. A statement was being made: that the message of the Reformation, Luther’s message, deserved to be arrayed in magnificence. In the process,

and thanks to Cranach’s decisive intervention, the Wittenberg book was catapulted from the back to the front of the pack in terms of aesthetic appeal.