Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (46 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Of all Luther’s writings none was more damaging to his later reputation, particularly in modern times, after these passages had been cited with such enthusiasm by the ideologues of National Socialism. Contemporary reaction was also decidedly tepid. Luther’s friends were by now

wearily familiar with the violent language with which he assailed the church’s enemies, and this intemperance would reach new heights in the writings of these last years. But whereas the last tirades against the pope found eager readers,

On the Jews and Their Lies

did not. Published twice in Wittenberg, it was not reprinted elsewhere in the original German.

34

Significantly, the authorities in Strasbourg, which by this date had become the largest Western center for reproductions of Luther’s works, intervened to prevent publication, for fear of possible violence. The print history gives a clear indication that, whatever their momentous later consequences, these works were at the time regarded as minor. Certainly Luther, harassed on all sides by political turbulence in Germany and premonitions of his own impending end, had other pressing preoccupations that demanded all of his attention.

Chief among these was the incessant, dangerous squabbling among the German princes. In 1539 the leaders of the Protestant alliance, Elector John Frederick and Philip of Hesse, became embroiled in a trial of strength with Duke Heinrich of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, a devoted Catholic and outspoken critic of Protestantism. Despite these strongly held views, the city of Braunschweig had embraced the Lutheran Reformation, with strong support from Wittenberg: Bugenhagen had drafted its church order, which was published in Wittenberg in 1528.

35

The local imperial city of Goslar was also a source of provocation to the duke. By supporting these demonstrations of independence, the Protestant princes were also engaging in a very obvious struggle for local political supremacy; by 1541 each side had accumulated an impressive quantity of grievances and provocations, and these were extensively ventilated in print.

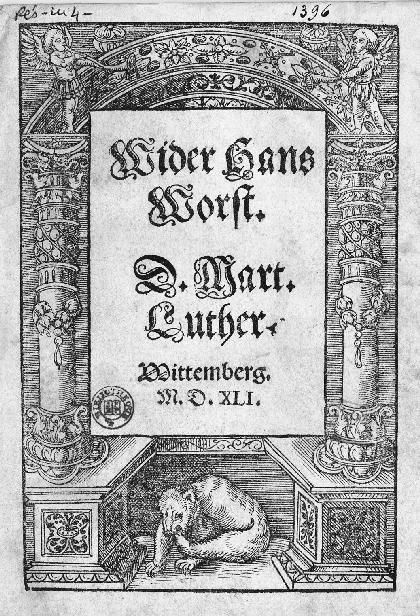

AGAINST HANSWURST

Much of Luther’s time in his later years was occupied trumpeting the cause of the Protestant princes. This violently abusive piece was an outraged denial that Luther had called his own prince, the corpulent John Frederick, “John Sausage.”

The quarrel called forth one of the most famous tracts of Luther’s last years,

Against Hanswurst

.

36

Hanswurst was a character taken from contemporary theater and farce, a dolt who wore a string of sausages around his neck; the inference for Duke Heinrich was not flattering. Luther, in fact, denied having characterized the duke in this

disrespectful

way. His offenses were far more serious: he was a devil, a coward, a murderer, and an adulterer.

The sustained invective of this tract reveals the depth of contempt that Luther felt for a man devoted to stamping out the Gospel in and around his territories. But this work was a solitary and possibly reluctant intervention into a furious print controversy driven forward by the princes themselves. In detailing his grievances, Heinrich was happy to dwell on Philip of Hesse’s marital misfortunes; John Frederick he characterized repeatedly as a corpulent drunk. This line of attack was perhaps not prudent as Heinrich also had a complicated love life. Having sired three children by his mistress, Heinrich offered her an elaborate church funeral, only for it later to be discovered that her death was a charade. Eva von Trott had, in fact, been hidden away so that the relationship could continue (as it did, with several more children).

This dirty washing was gleefully aired at the Imperial Diet of 1541, with little regard for the damage such charges and countercharges could do to the reputation of the princely caste as a whole. This pamphlet warfare generated over thirty different publications in 1541 alone, each more vituperative than the last. As so often, the elaborate titles left little to the imagination. Thus John Frederick’s

Second Treatise

was answered by Duke Heinrich’s

Well-Grounded, Steadfast, Grave, True, Godly, Christian, Nobly-Inclined Duplicae Against the Elector of Saxony’s Second Defamatory, Baseless, Fickle, Fabricated, Ungodly, Unchristian, Drunken, God-Detested Treatise

. It was to answer this that Luther had been called to the colors. But the princes also had their say, with the modestly titled

True, Steadfast, Well-Grounded, Christian and Sincere Reply to the Shameless, Calphurnic Book of Infamy and Lies by the Godless Accursed, Execrable Defamer, Evil-Working Barabbas, Also Whore-Addicted Holophernes of Braunschweig, Who Calls Himself Duke Heinrich the Younger

.

37

Evidently delighted with their handwork, the elector distributed three hundred copies of this work to those attending the Diet, and even had it translated into French so that the incredulous emperor might share in the spectacle. It is easy to think that Luther’s rather modest contribution to the debate may have been lost in

the noise, though

Against Hanswurst

enjoyed its own success, with translations into Latin, French, and Czech.

38

The whole, distasteful business usefully reminds us that the trenchant tone and flamboyant language of Luther’s polemics was by no means unusual in the inflamed atmosphere of 1540s Germany.

Confronting these unseemly and destructive quarrels, the Emperor Charles may have been forgiven for thinking that it would require decisive intervention on his part to bring peace to Germany. But for the moment his hands were tied; only in 1544 would he finally extricate himself from the debilitating warfare with France that had since 1538 consumed much of his attention and vast quantities of money. In the last desperate throes of this conflict, Charles had, in fact, made new concessions to Protestantism, assuring the princes that in return for financial support for his wars, the settlement of religion would await a “general, Christian, free Council in the German nation.” The pope, not surprisingly, was appalled at this clear encroachment on his own prerogatives and dispatched a stiff letter of protest. A copy of this private letter was soon in the hands of Martin Luther, most likely with the connivance of imperial officials. The Protestant princes urged Luther to reply, but in truth he needed little bidding. For in this, a defense of his church and the German nation against papal power, Luther had embarked on the last great polemical work of his life.

Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil

gave Luther the opportunity to return to the themes that had defined his career and encapsulated his life’s work.

39

The pope could not be head of the Church:

Rather [he] is the head of the accursed church of the very worst rascals on earth; vicar of the devil; an enemy of God; an opponent of Christ; and a destroyer of the church of Christ; a teacher of all lies, blasphemy, and idolatries; an arch-church-thief and church-robber of the keys [and] all the goods of both the church and the secular lords; . . . an Antichrist; a man of sin and child of perdition; a true werewolf.

40

Luther could now explain his concept of a true church, free of papal interference. A long historical excursus reviewed papal claims to primacy, deemed by Luther to be fraudulent. This learned exploration of Protestant historiography and the consideration of the scriptural passages generally taken to support the papal primacy have received less attention than the violence of the language and the earthy vulgarity: a crudity reinforced by a remarkable series of polemical illustrations, specially commissioned from the Cranach workshop.

41

Luther was closely involved in the design, allowing the woodcuts to be carefully aligned to key passages in the text. The penalty for the long history of papal “lies and deceit, blasphemy and idolatry” was that the tongues of the pope and his cardinals should be torn out and nailed to the gallows alongside their bodies. One of the woodcuts shows precisely this.

By this stage in his long career there was little to restrain Luther’s natural instinct toward polemical violence, particularly if, as in this case, he was acting with the explicit encouragement of the elector. Philip Melanchthon had long since given up on any attempt to restrain Luther’s extravagance of language; here it is given full rein. So, too, is Luther’s fondness for scatological abuse. But if we look beyond the steaming turds and farting (graphically represented with all Cranach’s customary skill), we should recognize the deadly seriousness of Luther’s purpose. This was a last call to arms, in these last days, against the papal Antichrist. This was the revelation that had led Luther outside the church, and this was the still imminent threat to the survival of his new church. If some were too delicate to recognize these truths, then so be it. As he reflected to Amsdorf:

[Y]ou know my nature, that I am not accustomed to attend to what displeases many provided that it is pious and useful and that it pleases the few good [people]. Nor do I think that those [who are displeased with it] are bad, but they either do not understand . . . the horrifying and horrible monstrosities of the papal abominations . . . or they fear the wrath of kings.

42

E

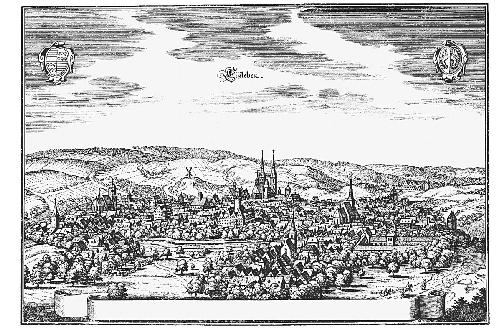

ISLEBEN

When Luther fell mortally ill in 1546 his presence in Eisleben, the town of his birth, was quite coincidental. The reformer seems to have felt it was the call of destiny, and swiftly reconciled himself to death.

In any case, it would soon fall to others to settle these questions without his guiding hand.

EISLEBEN

The demands of Protestant politics did not spare Martin Luther, even in his declining years. With the Peace of Crépy, the Emperor Charles was at last free to settle the matter of Germany. It swiftly became clear that he was determined to enforce his own settlement of the religious question. It was thus even more important that there should be no dissension among the Protestant princes. In the autumn of 1545 Luther was once more called into action, this time to mediate the quarrel between

the Count of Mansfeld and his brother Gerhard. Twice he traveled to Eisleben, the town of his birth, to promote reconciliation, an exhausting round trip of some 125 miles. A settlement was promised but was not yet achieved, so on January 23, 1546, he set off again, this time via Halle. Negotiations progressed well, but Luther was forced to absent himself from the final session on February 17 as he was suffering from chest pains. He was able to join his friends for supper, but the pains returned after he had retired to bed; it was quickly clear to Luther that this time there would be no recovery.

Luther’s church now faced a critical test. Much would depend on what occurred in the next few hours, and how Luther’s departing was represented to grieving followers or exultant foes. Luther had received a taste of what was in store in the previous year, when a false report of the reformer’s death had circulated in Italy. A maliciously hostile description of Luther’s passing was published as a broadsheet. According to this tendentious text, when Luther realized that he was dying, “he asked that his body should be placed on an altar and worshipped as a God.” But in the event:

No sooner had his corpse been laid in the grave than a terrible roar and noise were heard, as if devil and hell had collapsed. All those present were greatly terrified, frightened and afraid. . . . The following night everybody heard an even greater roaring at the place where Luther’s corpse had been buried. . . . When daylight came, they went to Luther’s grave and opened it. They saw clearly that there was neither body nor flesh nor bones nor clothes, but a sulfurous odor which sickened all those who stood around.