Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (41 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

L

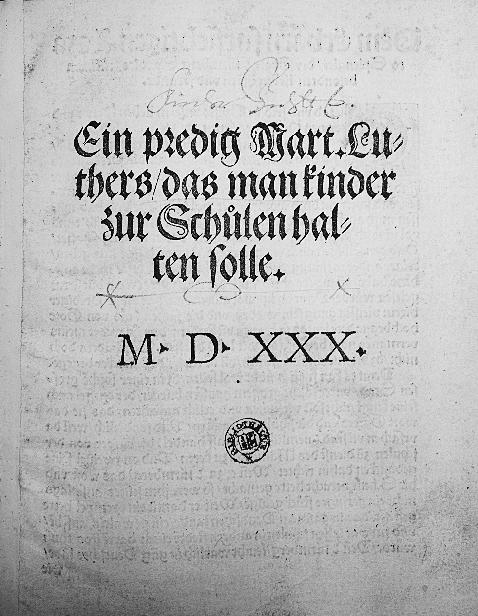

UTHER’S

SERMON ON KEEPING CHILDREN IN SCHOOL

Wittenberg was at the heart of an agricultural region, and Luther understood why parents were reluctant to send their children to school. It required the concerted efforts of church and magistrate to promote the virtues of literacy, but the rapid growth in educational provision was impressive.

Luther’s writing provides the essential context for understanding the enormous, and at first sight impressive, growth in educational provision in Lutheran Germany. New schools proliferated in the second quarter of the sixteenth century, first in the towns then rapidly advancing into smaller communities. But with Luther and Melanchthon the emphasis remained primarily on equipping the city elite for their tasks in church and state.

20

For the most part the clientele for such schools was confined

to the upper ranks of the urban citizenry, the patriciate and aspirant merchant class, the sort indeed likely to provide candidates for the new ministry and expanding state bureaucracies.

Such indeed were the social backgrounds of the young people flocking to the University of Wittenberg in ever-increasing numbers. The vast number of students now in Wittenberg brought its own challenges: an acute shortage of lodging and rampant inflation in the cost of basic foodstuffs.

21

The students were not always popular with the townsfolk, and frequently reciprocated this dislike. Nor was the booming matriculation register in Wittenberg necessarily reflected in enrollments of other universities in the German northeast, Erfurt and Leipzig. But demand was on a generally upward curve. With Luther’s prompting, a new university was founded in Königsberg in the recently Protestantized Brandenburg. The evangelical church would get its new educated clergy.

It took time to understand that this ideal of a Latin education could not be realized outside the main urban centers, but this lesson was gradually learned. This prompted the foundation of so-called German schools, teaching a more practical curriculum. By 1600 Württemberg had 401 schools spread among the duchy’s 512 communities, or one for every thousand in the population. Luther’s goal of universal provision, if not universal attendance, was now close to being realized.

Luther was also a notable pioneer in the field of female education. If the goal of an informed Christian people was to be realized, then this applied equally to girls as to boys. As early as 1520 Luther committed himself firmly to this cause. In his address

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation

Luther lamented that convents had abandoned their educational vocation. He called for the establishment of new schools for women: “And would to God that every city also had a girls’ school where the girls could hear the Gospel for an hour every day, whether in German or Latin.” Four years later it was the turn of the civic fathers of the German cities, whom Luther now exhorted to create “the best possible schools both for boys and girls in every locality.”

22

This pamphlet,

An die Ratsherren Aller Städte Deutschen Landes,

was one of the most widely circulated of Luther’s works in this period, with eleven editions published in a single year in eight different cities.

23

The cause of female education was pursued in all of the subsequent Lutheran church orders. In his church order for Braunschweig, Bugenhagen made provision for the regulation of the curriculum in the two existing Latin schools and the establishment of two new German schools for boys. In addition there were to be four schools for girls. Similar measures were adopted in the church orders of Lübeck, Hamburg, and other north German territories, as well as Wittenberg itself. The Wittenberg agenda was followed in Strasbourg, where Bucer made provision for the establishment of six girls’ schools, as well as the German southwest, where Brenz led the way.

The new girls’ schools generally followed a curriculum similar to that of the German boys’ schools; the Latin curriculum was reserved for the elite urban institutions. The establishment, so rapidly, of so many new schools was a tall order, both in terms of resources and provision of the necessary buildings; suitable teachers were also in short supply. Yet by the end of the century enormous strides had been made. The full measure of this achievement can best be gauged if we contrast Lutheran Germany with a survey taken of the schools of Venice in 1587. Venice had many schools with several thousand pupils, but of these girls made up a meager 0.2 percent. In Germany, in many rural areas, later surveys show that girls made up close to half the enrolled pupils,

24

Luther’s achievement as a pioneer in this field is seldom recognized; recent scholarship has preferred to focus more on the reformer’s rumbustious reflections on female frailties in the tipsy obiter dicta of the

Table Talk

. His real, passionate commitment to female education tells a different story. It deserves to be better known.

PRINTING THE REFORMATION

Catechisms and prayer books, Bibles and hymnals, sermons, church orders, and commentaries: the work of church building generated a huge volume of print, both for the use of the churches in Saxony and elsewhere in Germany. For the Wittenberg printing industry this was a golden period, the era in which it reached its full maturity. The pioneers of the first Reformation years, Rhau-Grunenberg and Lotter, were replaced by a new generation, whose work now moved Wittenberg into the first rank of the German print industry. Between 1530 and 1546 Wittenberg’s presses turned out over sixteen hundred editions, a total surpassed only by Nuremberg. Moreover, this total included many books of very substantial size; the short, cheap, easily produced pamphlets that had underpinned the first huge growth in the printing industry in Germany now played a diminished role in overall output.

Wittenberg’s printing industry took on a new solidity, dominated by four new workshops, all of which proved remarkably long-lived. Hans Lufft, who arrived in Wittenberg in 1523, would manage his workshop until 1584, when he died at the age of eighty-nine. His companions and competitors in this era, Georg Rhau, Nickel Schirlentz, and Joseph Klug, all sustained their enterprises for a generation or more. The manufacture, sale, and distribution of books was now Wittenberg’s largest industry, supplying churches and customers throughout Germany. At its heart was Martin Luther, still ceaselessly active in writing, apportioning work among the firms, and seeing books through the press.

The reconstruction of the Wittenberg printing industry entered a new phase with the arrival, between 1520 and 1525, of the four men who would come to dominate it. None, interestingly, had any previous connection to Wittenberg. Joseph Klug, initially employed to run the press established by Cranach and Döring, was the son of a Nuremberg printer.

25

Lufft may have been a printer’s apprentice; Rhau, a

schoolmaster, and Schirlentz were essentially new to the industry. All were attracted to Wittenberg by the apparently limitless possibilities opened up by Luther’s new movement. With the passage of Lotter and Rhau-Grunenberg, their four firms would together guide the Wittenberg industry into a new phase of expansion.

26

The key role in this transformation was played by Hans Lufft. His was by far the largest shop, and it made by far the most money. In a career of extraordinary length, Lufft, who published over nine hundred editions in Wittenberg, devoted himself entirely to the service of the Reformation. In the process he built both a close working relationship with Luther and a position of wealth and respect as one of Wittenberg’s leading citizens.

The critical moment of Lufft’s career was the decision of Lucas Cranach to withdraw from direct involvement in the printing industry following the collapse of his working relationship with Christian Döring. For Luther this may have come as something of a relief. Cranach and Döring had played an important role in the printing industry at an important time, providing the investment capital that the industry previously lacked and underwriting the cost of key ventures such as the publication of the first two editions of Luther’s New Testament. Cranach brought to his business dealings both real entrepreneurial flair and a certain ruthlessness. It was no secret that he hoped to exploit his friendship with Luther to establish an effective monopoly on the publication of the reformer’s new works. Luther, to his credit, resisted. He had sufficient understanding of the workings of the publishing industry to understand that this would spell disaster for other local firms. When in 1526 Cranach turned the printing shop over to its manager, Klug, Cranach could still retain his interest in the industry, since his workshop provided most of the illustrative material that appeared in Wittenberg books; but his withdrawal from direct involvement in printing allowed breathing space for others to grow. The work of publishing successive parts of the Bible now fell to Lufft, who over the next decade turned out

a number of elegant folio and quarto editions. This sequence culminated in 1534 with his magnificent edition of the complete Bible.

This was a book that could not be undertaken in a small shop: a folio of some six hundred leaves, lavishly illustrated with Cranach’s woodcuts, it would have been enormously expensive and time consuming to print. Lufft simplified the task by dividing the work into self-contained parts; this allowed the printing to proceed on several presses simultaneously. But the project still required enormous investment capital simply to purchase a sufficient quantity of paper and to keep the presses rolling. Happily the Lufft workshop was by this point a very well-established concern. Luther had played a considerable role in helping build its reputation and capacity by providing a steady sequence of lucrative and prestigious projects.

Lufft was, of course, not the only beneficiary of Luther’s patronage. While Lufft’s workshop was by some distance the largest in Wittenberg, Luther ensured that his competitors also had the chance to build a viable business. Luther’s works and other key texts critical to the Reformation were spread around all of Wittenberg’s different print shops: indeed, given the level of concentration in the Wittenberg industry on religious texts, none would have been viable without Luther’s support. The passing of the years brought no diminution of Luther’s fascination for the mechanics of the printing process. He remained closely involved in every aspect of the business—seeing his own texts and others in which he had a personal interest through the press, offering forthright advice to the printers, and reproving them for their derelictions, real and imagined.

As was the case when Luther was holed up in the Wartburg in 1521, we only get a full sense of Luther’s day-to-day involvement with the printing industry when he was forced to spend an extended period away from Wittenberg. In such circumstances he was obliged to commit to paper the sort of advice and instructions that would usually be conveyed in person. One such period coincided with the negotiations surrounding the planned evangelical confession of faith at the Imperial Diet of

Augsburg in 1530. Luther, as an outlaw, could not join the other Wittenberg delegates in Augsburg. He accompanied them only as far as Coburg Castle, where he remained for several months, observing events from afar and offering Melanchthon and other colleagues a running commentary on developments and advice on their conduct of negotiations.

This was an anxious and frustrating time for Luther, separated from home yet far from the center of events. As so often, he poured his energies into a fury of creative writing. Interestingly, the eleven new works he completed during this period were distributed among five different Wittenberg printers. Lufft had four, Schirlentz three, and Rhau two; this left one each for Klug and another relative newcomer, Hans Weiss.

27

Weiss’s print shop was by far the smallest then operating in Wittenberg, with only ninety-seven known editions published in fifteen years. But he was not for that reason neglected by Luther; indeed, the reformer was disproportionately generous to what was in effect a boutique business. More than half of the modest output of Weiss’s shop consisted of works by Luther.

In addition to the careful apportionment of the first editions of Luther’s own works, the reformers ensured that all of the Wittenberg printing houses were able to build their own particular specialism. In addition to his grip on the publishing of the Wittenberg Bible, Lufft was responsible for printing Luther’s

Betbuchlein

and the postils. Joseph Klug was responsible for the German songbook and a large proportion of the scholarly works of the university community. He was, for instance, Melanchthon’s favored printer. Klug was also the first in Wittenberg to print with Hebrew type.