Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (44 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

In return for such favors Luther was naturally expected to attend to the electors’ affairs. Luther was fully aware that imperial politics would determine the course of the Reformation every bit as much as sermons and true teaching. How he chose to reflect this insight in his dealings with his patrons required a subtle balancing of dependence and the evocation of his authority as pastor and prophet. The relationship with his original protector, Frederick the Wise, was one of extraordinary singularity; few in the imperial court could really fathom what motivated Frederick in his protection of Luther. It speaks volumes that in 1522, when Frederick was dealing with the dangerous fallout of his decision to protect Luther from imperial condemnation, he also sent his agents to Venice to purchase more relics for his collection.

4

Luther owed Frederick his life; but if he recognized the extraordinary skill with which Frederick had protected him, he sometimes chose strange ways to show this. Frederick had shielded Luther by sending him to the Wartburg, and given clear instructions that Luther should remain there until he felt it safe for him to reemerge. Luther decided, nevertheless, to return to Wittenberg, and he announced this extraordinary act of disobedience in a letter of breathtaking rudeness.

I am going to Wittenberg under a far higher protection than the Elector’s. I have no intention of asking Your Electoral Grace for protection. Indeed I think I shall protect Your Electoral Grace more than you are able to protect me. And if I thought that Your

Electoral Grace could and would protect me, I should not go. The sword ought not and cannot help a matter of this kind. God alone must do it, and without the solicitude and co-operation of men. Consequently he who believes the most can protect the most. And since I have the impression that Your Electoral Grace is still quite weak in faith, I can by no means regard Your Electoral Grace as the man to protect and save me.

5

In 1525 Frederick died, to be succeeded by his brother John. In one respect this made life easier for Luther, since Elector John was a firm supporter of the Reformation. His succession allowed the Wittenberg theologians to complete the work of transforming the churches in the electorate for evangelical worship. But the new elector was also politically cautious and anxious to remain on reasonable terms with his cousin, Duke George, ruler of Ducal Saxony and Luther’s most ardent critic. In the years around 1530, as the relationship between Protestant and Catholic powers in the Empire became ever more strained, John came under heavy pressure to offer the coalescing Protestant forces more forceful leadership. The directing spirit behind this more aggressive policy was Landgrave Philip of Hesse, ruler of a substantial territory in central Germany. Philip’s decision to convert his lands to the Reformation was very much his own. His first direct contact with Luther was as late as 1526, when the two men exchanged letters.

6

Luther seems not to have warmed to Philip, who had taken a leading role in the brutal suppression of the peasant armies in 1525, and now seemed bent on confrontation with the Catholic states. But it was impossible not to engage with this political agenda, especially when Elector John threw in his lot with Philip.

Luther now had to face the possibility—indeed, the likelihood—that the princes would take up arms against their sovereign lord, the Emperor Charles V. This went against all his instincts, and indeed, his previous pronouncements on the subject of civil authority. In practice, however, he could not put himself at odds with the movement’s protectors. The

result was a work, the

Warning to His Dear German People,

which, while not explicitly endorsing resistance, nevertheless gave every encouragement to the Protestant leadership with its forthright denunciation of the Catholics and their proceedings. If it came to war then the Catholics would be to blame. Furthermore, Luther would not condemn those who took up arms to defend the righteous cause.

[S]hould it come to war—which God forbid—I will not have rebuked as rebellious those who offer armed resistance to the murderous and bloodthirsty papists, but rather I will let it go and allow them to call it self-defense, and will thereby direct them to the law and to the jurists. For in such a case, when the murderers and bloodhounds wish to wage war and to murder, it is also in truth no rebellion to oppose them and to defend oneself.

7

Luther had given the princes what they needed. Without having to repudiate his previous views, he had given his tacit consent to the armed struggle. Not surprisingly the delighted leadership of the new Schmalkaldic League ensured that the

Warning

was widely circulated, both on its first publication in 1531, and again on the outbreak of the Schmalkaldic War in 1546.

8

Luther had done his duty, but the special pleading in this piece was fairly threadbare. Catholics were quick to exploit his discomfiture, among them the redoubtable and persistent Duke George. For Luther the duke was a formidable foe. In many respects, as Luther acknowledged, he was a thoroughly admirable man, even the model of a Christian prince. He was educated, thoughtful, and moderate, certainly as capable a theologian as the more boisterous Henry VIII of England. He was also a genuine reformer.

9

For all these reasons he had a capacity to needle Luther that many would have envied. His lands were strategically placed to impede the distribution of books from Wittenberg, not least by closing to them the important Leipzig market; his constant complaints about Luther also had an impact on his cousins in Electoral Saxony. In

1531 he took aim against Luther’s

Warning,

in a well-reasoned and cleverly argued dissection that exposed the evident contradictions in Luther’s position.

Luther has now recently published a treatise once again which he called “A Warning To His Dear Germans,” but which with more justice might be called an enticement and guide to disobedience and rebellion. For in it he basically seeks nothing else but to make us Germans disloyal to the emperor and insubordinate to all authority.

This for the clear-sighted duke was the nub of the matter. The princes’ military preparations were clearly at odds with the reformer’s teaching, that the Gospel could not be maintained by the sword, but by the power of God, “as Luther himself . . . had often indicated.”

10

Luther’s response was a brutal tirade,

Against the Assassin of Dresden

.

11

While purporting not to know the author of the duke’s original attack, this was aimed squarely at George, charging the Catholics with responsibility for the impending armed struggle. Luther was sufficiently provoked to send this to the press without having sought the approval of Elector John, who had, in fact, specifically forbidden any further attacks on Duke George. This act of defiance went unpunished; it did, after all, suit the purpose of the Protestant princes that Luther should be drawn ever more openly into defense of their cause.

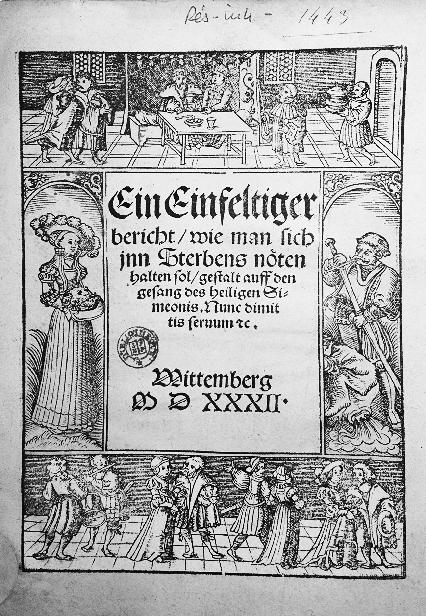

The succession of John Frederick in 1532 brought a further significant shift. Frederick the Wise and his brother had both been, in their different ways, a restraining influence on Luther. John Frederick was a much younger man (twenty-nine when he began his reign) and a staunch advocate of the Reformation. Rather than restraining Luther he encouraged him to go on the offensive. When Duke George took action against those in Leipzig who surreptitiously followed the evangelical way, Luther took up the cudgels in their defense. His

Vindication Against Duke George’s Charge of Rebellion

went through six Wittenberg editions in 1533,

all published by Schirlentz; his

Short Answer

to Duke George’s response, a further two from Lufft (also the publisher of the

Warning

and

Against the Assassin

).

12

Unseemly it may have been, but it did good business for the printers. It also drew Luther ever more closely into the role of principal propagandist for the Protestant princes.

For this, there would eventually be a price to be paid. It came in 1539, when the personal affairs of Philip of Hesse reached a crisis.

13

Philip was locked into a loveless dynastic marriage. Like many in such a position he took solace in another relationship, with the young Saxon noblewoman Margarethe von der Saale. Troubled in his conscience, he now wished to marry Margarethe, but without divorcing the estranged Christina, the daughter of George of Saxony. He approached the Wittenberg reformers, through Martin Bucer, to ask their blessing for a bigamous marriage. This was an impossibility, condemned by the law of the church and the Empire, and punishable by death. But the consequence that an embittered Philip would abandon the evangelical cause was too awful to contemplate. Somehow Melanchthon’s subtle mind offered a way through these impenetrable thickets. The theologians would tolerate in this exceptional case a bigamous marriage, so long as it was kept a secret. They would make no public statement, but offered this counsel only under the seal of the confessional.

Of course, such a secret could not be kept. When the truth leaked out, along with the complicity of the Wittenberg reformers, it did untold damage both to Luther’s reputation and to the evangelical cause. Luther remained relatively sanguine, Melanchthon much less so; not for the first time when faced by a crisis Luther’s fragile health gave way. For a time his life was despaired of. For a movement that drew much of its moral capital from Luther’s reputation for straight dealing and plain speaking, the sordid nature of this episode and Melanchthon’s sophistry did great damage. But the reformers had little choice. In giving his name to this squalid bargain, Luther was doing no more than recognizing the essential truth that now shaped the future of his movement:

that its survival depended on the support and leadership of Germany’s Protestant princes. It may have been the cities that had shown the vital early enthusiasm for Luther’s teaching; it was certainly in the cities that his printed works found the most readers. But it was the princes who by adhering to the movement could create the territorial churches that gave Luther’s movement its stability and political muscle. The price, as Luther and Philip both knew, was that the reformers could not refuse the comfort they offered the landgrave to preserve his leadership of the movement.

S

ERMONS

H

ONORING THE

D

EAD

D

UKE

J

OHN OF

S

AXONY

A beautiful product of the Cranach workshop, but was Salome really appropriate for such a solemn purpose?

SIGNS AND WONDERS

In December 1532 the Leipzig preacher Johann Koss suffered a catastrophic stroke in the pulpit while attacking Martin Luther. He died shortly thereafter. Luther viewed this as a manifest sign of God’s judgment—like all his contemporaries, he had no doubt that the Almighty would and did intervene directly to shape affairs according to his will.

14

The end of the same decade brought further decisive signs of God’s favor, not least in the fateful resolution of the succession in Ducal Saxony. In 1537 Luther’s old adversary Duke George had suffered a critical blow with the death of his son John. Only one son, the mentally handicapped Frederick, now stood between him and the accession of his evangelical brother, Duke Henry. The desperate Duke George somehow contrived a bride for the feeble Frederick, but in February 1539 he, too, died; two months later George also passed away. Luther had no doubt that these family calamities were a judgment on George’s sins, the awful cost of resisting God’s will. The new Duke Henry swiftly moved Ducal Saxony into the evangelical fold. But the brightening prospects in Saxony were in these years a rare ray of light in a darkening political perspective. All around, the Reformation was assailed, a fragile plant beset by winds and torrents. How were these more ominous events to be interpreted?

Luther and Melanchthon were, like many contemporary theologians, eager students of astrology.

15

Scholars scanned the heavens for intimations of God’s purpose; the less cautious offered predictions of future events based on these observations. Both reformers also shared the widespread fascination with human and animal misbirths, what they might mean or portend. As Luther put it in a preface to the prophecies of Johann Lichtenberger, published in 1527:

God also makes His signs in the heavens if a misfortune is to occur and causes shooting stars to appear, or sun and moon to darken, or

some other unusual manifestation to appear, also [when] abominable horrors are born on earth to both man and animal, all of which are not done by the angels but only by God Himself. With such signs He threatens the godless and indicates disasters coming upon lord and land, in order to warn them.

16