Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (42 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Schirlentz enjoyed the local monopoly on the publication of the

Small Catechism,

a book in fairly constant demand in Wittenberg and elsewhere. Schirlentz was an interesting case, because when he first arrived in 1521 he set up shop in the house of Andreas von Karlstadt. The association with Luther’s soon disgraced colleague seems to have done him no harm. Over the years before his death in 1547 he printed 143 of Luther’s works, an impressive 40 percent of his total output. Finally, in this

division of labor, the workshop of Georg Rhau was allocated the

Large Catechism,

editions of the

Confessio Augustana,

and Melanchthon’s

Apologia

. Within the constraints of Luther’s relationship with the much larger business of Lufft, Rhau seems to have been something of a favorite. Luther regarded him as especially reliable, and Rhau also held the valuable privilege of publishing official mandates and proclamations for the elector.

28

In 1546 this contract required him to equip a field press to accompany the elector on campaign, where he would be on hand for the printing of orders from the camp or news of the army’s military success. Sadly for the Protestant cause such dispatches proved to be in short supply, and Rhau’s press was impounded by the victorious Catholic forces after the calamity of Mühlberg.

29

In the century after the invention of printing it had not taken those active in Europe’s new publishing industry long to realize that competition among them could be ruinous. In addition to the protections provided by the state to reward investment, the industry developed its own mechanisms to ensure that different printers operating in the same markets did not cut each other’s throats. These informal systems worked differently from place to place. In Paris the industry developed a complex series of alliances between its leading families, which effectively froze out newcomers and prevented them from gaining a foothold. But Wittenberg provides the only example in which the division of labor was effectively decided and enforced by the informal influence of a single powerful arbiter: a man who was simultaneously the leader of the local church and its leading author.

Unusual this may have been, but Luther exercised this role with great gusto, as the letters penned from Coburg make clear. At the end of April 1530 he determined to stiffen the resolve of Wittenberg’s negotiators with an

Admonition to the Clergy Assembled at the Reichstag

. The manuscript of this text was dispatched 150 miles north for printing in Wittenberg. On June 2, Luther received copies from a messenger hurrying south to capture the market in Augsburg before a competing pirate edition could be published locally. This was duly achieved: on June 13,

Justus Jonas reported from the Diet that five hundred copies had been sold.

30

This complex procedure required a 300-mile round trip for the text of Luther’s manuscript, and a further 150-mile journey to Augsburg for the printed copies. But Luther knew what he was about. There may have been a printer available more conveniently placed nearer to Augsburg, but Luther trusted Lufft to make a good job of a critical text. Luther also wanted to reserve for Wittenberg the first edition of a book likely to sell well. This proved to be wise. By the end of the year, the

Admonition

had been reproduced in five other cities, and in a Wittenberg reprint by Klug.

31

But not in Augsburg; there the Lufft edition had cornered the market.

Luther was solicitous of his friends in the printing industry, but also demanding. He harbored dark suspicions, particularly when brooding in the enforced seclusion of Coburg, that his wishes were not always respected when he was not there to keep the printers up to the mark. Luther continued to spend a lot of time in and out of the print shops, as did many prudent authors. We catch echoes of this in his prefaces: “I have gladly seen this little book into print, as I have done before with several others.”

32

But he knew also that the printers were first and foremost businessmen bent on profit. It did not need much to incite suspicions that without his commanding presence in Wittenberg the printers would consult their own best interest rather than his. First Lufft attracted Luther’s ire by delaying publication of a book in which the reformer was involved, apparently so that publication would coincide with the autumn fair in Frankfurt.

33

Now it seemed that Schirlentz, offered Luther’s

Sermon on Keeping Children in School,

planned to shelve it for the winter to catch the spring fair. Luther was beside himself. Katharina was ordered to march into the shop, remove the manuscript, and reassign it to Rhau.

34

In September it was Weiss in the firing line, this time for refusing to publish Luther’s

Exposition of Psalm 117.

Why had he not wanted to do it?

35

Actually the reason was clear enough, since Luther had already had this work printed in Coburg (a goodwill gift to a very small local shop).

36

Weiss felt he could not take the risk that the market was sufficiently large for a reprint. Luther ordered this work also to be reassigned to Rhau. Luther’s correspondents knew to take these outbursts with a pinch of salt. The impatient reformer had judged Schirlentz too harshly: a copy of the

Sermon

was already on its way and crossed Luther’s angry letter on the road. And there were no hard feelings for Weiss, who published original Luther works every year between 1525 and 1532.

Luther’s attitude to the printing of his works had undergone a substantial change over the course of the years since 1517. In the first years his only priority was to see his works in the public domain; he welcomed the widest possible distribution through frequent reprints around Germany. From 1519 he recognized the need to recruit capable printers to Wittenberg, partly to improve the speed of production, but also so that the appearance and quality of Wittenberg editions did justice to his developing theology and movement. Now, in the 1530s, with the Reformation an established fact, Luther was increasingly concerned to retain for his own city as substantial a portion of his printed output as possible.

This was not solely for commercial reasons, although the publishing industry was now a cornerstone of the Wittenberg economy. Luther was also concerned that the canonical texts of the movement should be published accurately and without error or amendment. Luther had been sensitized to this issue during the early stages of the dispute with Zurich, when a well-meaning intervention of the Strasbourg reformer Martin Bucer caused great offense. In 1526 Bucer had sought and obtained permission from Johannes Bugenhagen to translate his Psalter into German. Bucer’s translated text, however, incorporated a spiritual interpretation of the Lord’s Supper far closer to the position of Zurich. The accompanying translation into Latin of Luther’s fourth postil included a commentary criticizing the Wittenberg position on the Eucharist. Luther was furious, particularly as the Bugenhagen work included separate prefaces by both Luther and Melanchthon: it might, therefore, seem that this shift in meaning had their endorsement.

37

Luther had a long memory for sharp practice of this sort. When in

1536 Wolfgang Capito approached Luther to see if the reformer would authorize a Strasbourg edition of his collected Latin works that Capito and Bucer wished to publish, Luther indicated that he would not grant his consent.

38

When the long-planned collective edition was eventually put in hand, the task was reserved for Wittenberg and the reliable Hans Lufft.

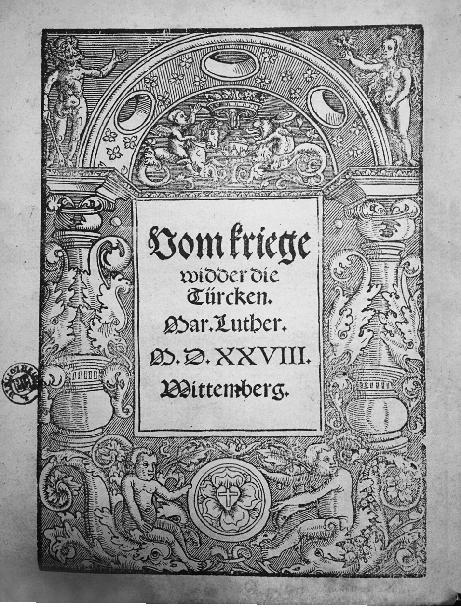

C

ONCERNING

W

AR

A

GAINST

THE

T

URKS

The publisher Hans Weiss ran one of Wittenberg’s smaller print shops. Nevertheless Luther was still generous in the allocation of his compositions, as in the case of this exhortation to solidarity against the Turk.

The degree of control that Luther exercised over the publication of his works was by this point very striking. We remember that when Johann Froben of Basel was moved to exploit the sudden interest in the

Luther controversies in 1518, he did not think to ask Luther’s permission before publishing a miscellany of his writings on indulgences. Indeed, it was only some months later that he thought to send Luther a copy.

39

A decade later such a casual appropriation of Luther’s intellectual property would have been rash for any established publisher in one of Germany’s evangelical cities.

THE POWER OF PATRONAGE

In the last fifteen years of his life Luther exercised an extraordinary influence over the output of the German press. Wittenberg’s printers revered him for the amount of work he could put their way, and not just his own writings. In 1531 the town council of Göttingen dispatched their new church order to Luther, along with an honorarium, asking him to review and if necessary correct it. This work done, Luther passed it to Hans Lufft with his own approving preface, but without apparently passing it back to Göttingen for final copy approval.

40

The same procedure was followed for Brenz’s commentary on Amos. Luther received this work while in residence at the Coburg, before sending it north for printing in Wittenberg. Presumably from there a large part of the edition would have been sent back to Brenz for distribution in southern Germany. Brenz was a substantial figure in the movement, and Luther’s preface contained a gracious acknowledgment that such a fine theologian scarcely required Luther’s imprimatur; but Wittenberg still got the work.

Many other lesser lights also sent writings to Luther in the hope that he would read and approve of them. Luther recognized the danger that he would become, in effect, his movement’s chief censor. “One of your [Erfurt] preachers, Herr Justus Menius, has sent me a little book that he composed against the Franciscan monastery in your city, so that I should judge whether it might be sufficiently deserving of publication. Now, I have no intention—and may God guard me against it—of taking

upon myself to be judge or ruler over other preachers, lest I start my own papacy.” But, he continued, “I am obligated—and indeed, am glad to do so—to serve everyone, by bearing witness to his doctrine where it is correct. . . . Accordingly I give this little book my attestation.”

41

By this point most of the cities and territories of Germany had introduced some form of control of the contents of books printed locally, mostly by establishing, in theory at least, the requirement for prior inspection of any texts likely to prove controversial.

42

In Wittenberg it was expected that the members of the university would submit their texts for approval by the faculty; most indeed voluntarily sought the opinion of colleagues, as did aspiring authors from outside the city. In 1525 Johann Toltz, a schoolmaster from Plauen, some 125 miles south of Wittenberg, sent his small catechismal handbook to the university for approval. The task was assigned to Bugenhagen, who on December 18 was able to testify that “according to my understanding I know nothing else than that this booklet is godly and useful.”

43

The text was then passed to Georg Rhau for publication.

Plauen had no press, so this apparently voluntary act was probably a necessary preliminary for an aspiring author like Toltz if he was to find a printer. The Wittenberg printers in any case would by this stage not have printed anything from an unknown author without assuring themselves that the work was doctrinally sound. They simply would not print anything that they thought Luther would disapprove of, for fear that the reformer would withdraw his patronage. The awful example of Melchior Lotter hung heavy on the memory.

44

In this respect by far the most important control of the press in Wittenberg was self-censorship by the printers.

A revealing indication of the strength of this sentiment comes from letters exchanged between the printer Georg Rhau and his brother-in-law in 1527. Rhau wished to put to the press an edition of the popular catechismal text the

Buchlin,

edited by the Zwickau town secretary (

Stadtschreiber

) Stephan Roth. Roth was a man of high reputation, but Rhau was taking no chances. He waited three months before he could

report the happy news that “Doctor Martin has permitted me to publish my prayer booklet, which you organized, and as soon as I have nothing else to print, I will typeset it and get someone to make woodcuts for it right away.

45